Arts & Culture

And Niriko Makes Four

Ahead of Father’s Day, the writer Lolis Eric Elie reflects on the other Lolises in his life—his late father, and his new son

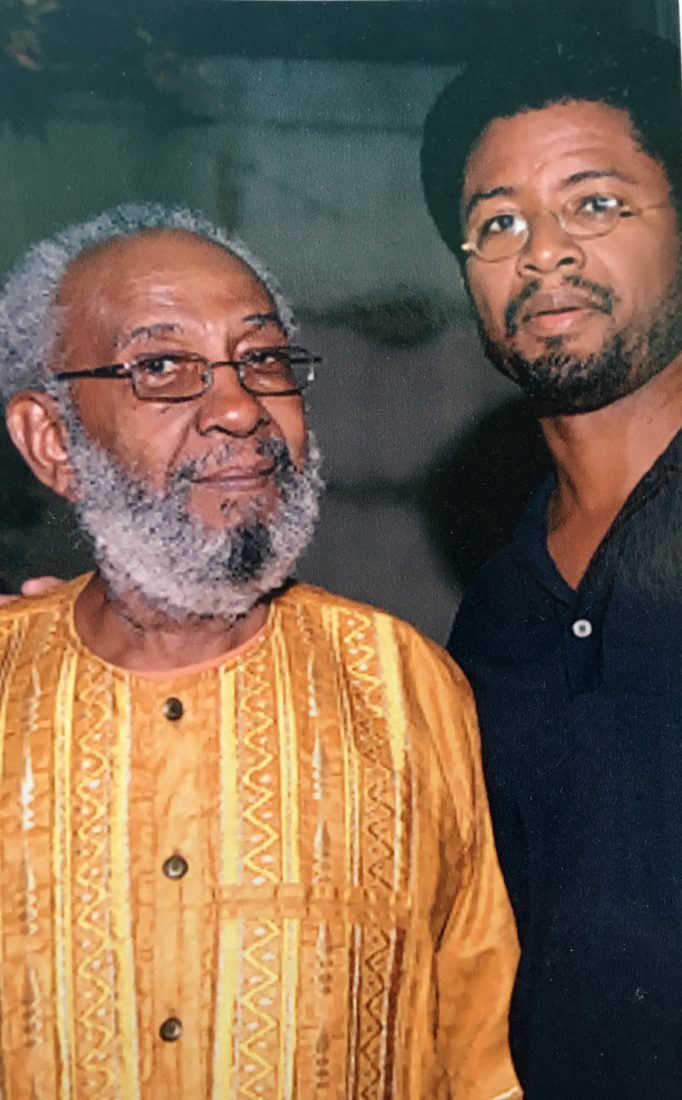

Photo: Pableaux Johnson

The New Orleans native Lolis Eric Elie is a former Times-Picayune columnist and cookbook author who has written for the Oprah Winfrey Network show Greenleaf and the HBO series Treme. The following essay is excerpted from the forthcoming Apple, Tree: Writers on Their Parents, an anthology of essays to be published by the University of Nebraska Press in September 2019. Here, Elie meditates on the name he passed down to his new son, and in turn on his father, the civil rights attorney and pioneer Lolis Edward Elie.

There’s something I wanted to tell you, wish I could have told you in those last few days when you hovered at the crossroads between this world and that: You have a grandson. Lolis Niriko.

He wasn’t born then. Indeed he had been scarcely imagined. I had met his mother already, but only through phone and email.

You never said you wanted grandchildren. Was it irony or poetic justice that led your granddaughter, Tyese—the child of the child you fathered before you met my mother—from Harlem to your doorstep several months into your dotage? In your more lucid moments, you could remember who she was and brag to friends about the impressive young woman in the new picture on your mantel. But those moments were spacing themselves further and further apart. I told Tye that, had she come even a year earlier, you would have feted her like the biblical father feted his prodigal son. You would have shown her off at Upperline and Commander’s Palace and Dooky Chase’s and popped bottles of Champagne until everyone had drunk their fill.

Or were you the prodigal, having absented yourself from her late mother’s life so many years before?

Be that as it may, coming when she did, she got only the ghost of her grandfather and the photos and videos I have since sent. My son is too late even for that.

Béa, Lolis Niriko’s mother, is from Madagascar. Your grandson is Malagasy. Born of an African island about as far away from New Orleans as one can get. “The African intellectuals are superior to the black American ones,” you once said, and I took it as a kind of gospel as I was wont to do in my formative years when it seemed that, if you didn’t know everything, you knew everything worth knowing. That statement, like so many of your grander pronouncements, has not held up. But statements like that led me to Africa again and again. Your politics helped shape my geography.

Vaughn Fauria—friend of yours, friend of mine, younger than you, older than me—was sometimes a bridge between us. She said that your inclination to grand statement and grandstanding had everything to do with your youth in the neighborhood then known as “Niggertown.” In that small, dark corner of New Orleans, where so much of the world’s knowledge and light was forbidden from crossing the color line, it must have been great sport to boast of knowing more about the world outside that world than anyone knew within it. Who among those residing there could have checked the facts? I suppose that’s what empowered my grandfather, Theophile Jones Elie Sr., to tell his neighbors that he went to the World Series every year. He did wear a coat and tie when he went to his job driving a truck. I suppose somehow that counts as seeing a larger world within yourself, does it not?

From left: Lolis Edward and Lolis Eric Elie in the late 1990s.

An old girlfriend of mine once said that I was quick to offer my commentary, whether I was familiar with the subject matter at hand or not. When I realized she was right, I resolved that my knowledge and my words should be more directly proportional. You used to quote Gandhi, saying, “I go from truth to truth.” Which is to say, “As I get more knowledge, my position may shift.” I’ve never been able verify that Gandhi said that. It might have been original to you.

You told me a story once of your father coming to our house after church one Sunday. No doubt my mother, my sister, and I were still at our own church, Bethany United Methodist, that place you stopped attending when the congregation thought it more important to build a new sanctuary than to minister to the poor and afflicted in the nearby Desire Public Housing Development. As I recall it, you were driving along St. Charles Avenue, that grand product of cotton blood and sugar blood. Black blood. You asked your father if he had ever thought that he deserved one of those great mansions of his own. A light went off or a revelation landed or whatever it was that you said happened to him. The metaphor doesn’t matter. The point is that people like us deserved mansions like those, and if we failed to attain them, it should not be for lack of belief in our own worthiness and worth.

You never doubted your worthiness, that’s for sure. But your interest in saving the sons and daughters and cousins and kinfolks of the people in the Desire and Niggertown and elsewhere was always more important than amassing the money those blood mansions demanded. I remember one woman Richard Nixon accused of welfare fraud during one of his many efforts to get Watergate off the front page of the newspaper and welfare recipients onto it. You served as her lawyer for free, as if the act was striking a blow at Tricky Dick himself. You told me later that when she had a personal injury case, a case that could have actually earned a lawyer a few dollars for relatively little work, she hired a white man. By the time you told me that, it was an old story and your bitterness had faded or been buried.

Your tax trouble was a mistake of your own making, though. Your friend Leonard Dreyfus gave you the money ($10,000 was it?) to pay the IRS debt. But by then, the white folk in nearby Hahnville had railroaded sixteen-year-old Gary Tyler to the distinction of being the youngest person on death row in Angola State Penitentiary. A white boy had been shot during school desegregation. Some black boy had to pay. You appointed yourself to the task of helping with Tyler’s legal appeal, using the tax money to pay your bills. Forty years later, Gary Tyler was finally out of jail. When I met him, he thanked me for your work. By that time, you were remembering less and less.

In college, I was president of the Black Students League. If we could just commit ourselves to “the struggle,” I thought—a struggle that straddled divestment from South Africa, more black faculty, more black students—we could accomplish it all. Have it all. Your optimism was my optimism. I helped lead a big movement of black students during my senior year.

If I were to have been expelled for my activity, not that it ever came anywhere near that, I was confident that I’d be welcomed home a hero. It felt good when you came to visit and heard the professors praising that work. You used to say that the family business was the shoeshine stand in Niggertown, where you learned the trade you would later ply on the streets of midtown Manhattan. Lacking the skill to blacken boots, I decided that the family business had something to do with social service.

You used to say that most of these black leaders who jump in front of the television cameras, if they were ever called to account for their stewardship, would have little to show for themselves. “Stewardship?” Perhaps you did gain something, at least a little, from all those years your mother and my mother insisted that you go to church. I always wanted to be sure that I could account for my stewardship, that wherever I was, I did my part. And I shared your impatience with those who didn’t.

You loved Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, especially the section when the narrator realizes that the president of his Negro college has lied to him. My favorite passage from that book concerned the college’s founder: Was he lifting the veil of ignorance from the Negro or holding it more firmly in place? I inherited your contempt for those kinds of people, those people who won the praise of white people for their stewardship precisely because it was so antithetical to our interests.

You never tired of telling the story of the day we were eating lunch at Palace Café and ran into Revius Ortique. His civil rights credentials were invented and inflated, you would say. A veteran of the civil rights movement yourself, your contempt for him was palpable.

We had arrived just as he and his party were finishing their meal. You made it clear to me with that wave-of-the-hands gesture of yours that you wished he would not come over and speak to us. So of course he did. He came to our table to brag on how much business had been set aside for black contractors at the airport. I was fine for a moment. But when he went on and on about all he had done, I could no longer be civil. I don’t remember the pointed questions I asked him, but he seemed genuinely surprised that I doubted his heroism. Was that because of the things you had told me about him? Perhaps. But maybe it was because I remembered, as you never forgot, another story of black leaders claiming to help but actually hurting black business, black progress. Rhodes Limousine Service, the black-owned company, had a contract to pick up travelers at the airport. Though Ortique was not chairman of the New Orleans Aviation Board then, it was a black mayor, Dutch Morial, who stripped that contract from Rhodes and gave it to a white company. Then Morial added insult to injury by allowing that white company to raise the rates it charged. When Rhodes had made that request, they were denied.

Perhaps I should have been gentler years later when I wrote a newspaper column about the airport changing its name to honor native son Louis Armstrong. I interviewed Ortique about whether jazz musicians would benefit from this belated recognition of one of their own. Ortique, an old man by then, seemed genuinely offended at the thought of paying musicians to perform. When I pointed out that lawyers were routinely paid by the airport, he explained to me that lawyers are professionals. My reaction, as someone whose father took him to jazz clubs years before he was old enough to be legally admitted, was fiery. I wrote a scathing column that was as much a rebuke of that one man as it was a rebuke of all the “Negro” leaders who denigrated black cultural expression.

Which is to say, I have something of your hair-trigger temper. This inclination of politicians to offer me shit and tell me it’s Shinola has always riled me. I sometimes wish I could control the impulse better. Then I think of the writer Christopher Hitchens, whose reaction upon being told he was a knee-jerk liberal was that he would be gravely concerned if, when faced with certain stimuli, his knee failed to jerk.

You would have said that this impulse in you came from your uncle Edward, whom you never actually knew. He and his wife raised your mother, which is why she made Edward your middle name. He was so radical, your mother told you, the priest turned his casket away at the Catholic graveyard. I’m not sure what Edward could have done in Point Coupee Parish that was bad enough to piss off that white priest (but not so bad as to get him lynched). Whatever it was, you took great pride in it. I didn’t hear this story until I was grown. By then I knew that, though my first name was, like yours, Lolis, the plan was to call me by my middle name, Eric, the thirty-first most popular American boys’ name in the year of my birth.

Long before my son was born, I knew that he would share our first name, the family name, but that he’d be a junior to neither of us. His middle name would be an African name, I knew. (Neither the Arabs nor the Europeans need our continued help in propagating their names.) “Niriko” his mother decided. It means “what I desire” in Malagasy, and it captured both our attitudes.

***

Béa doesn’t like dogs, or at least not big ones. This I learned after renting us a room at a bed and breakfast where the owners had two large dogs and several small ones. Learning that about her made me think of you. You never liked dogs either. You swore that your father had spent far less time with you and your eight siblings than he did with his German shepherds. You were determined to exceed that low bar, and you did.

With you I discovered the joys of the Vieux Carré. There were the French Quarter walks, the potato-onion-cheese omelets, the restaurants, the trips to Navarre Beach, that Romare Bearden exhibit at the Contemporary Arts Center. You taught me the beauty of old buildings.

You also taught me the necessity of covering tropical plants when freezing weather is in the forecast. When you were growing up, your mother and sister, Mary Elizabeth and Auntie Odette, kept a rose garden in the front of the shotgun double they shared with their children. You took great pride in that. Living in Niggertown didn’t have to mean living without beauty, you used to say.

You predicted that I would come to love gardens one day. This you said as we engaged in the hard winter work of moving the large collection of bromeliads that resided in the courtyard you shared with James Dombrowski, the old radical. Watering the flowerbed was a daily job at my mother’s house, often done while other kids were playing football in the street or artfully doing nothing on someone’s front porch. The idea that I would voluntarily garden counted among your crazier predications. Perhaps I remembered it because of its insanity.

Insanity is well rooted in this family.

Last week, I planted coleus and canna and bird of paradise in the garden of the house I just moved into. It took me four months to actually do the work. Like you, I was not anxious to get on my hands and knees in the dirt to arrange plants and spread mulch. But like you and your mother, Mama Lizzie, and my mother and her mother, Grammy, I couldn’t bear the thought of coming home to a house with little in the front yard but grass and plain, green bushes.

Then there’s the story my mother tells of a day before you had left us. She wasn’t feeling well, and you agreed to watch my sister and me while she took a nap. She woke to find us alone and you somewhere else. On the golf course, maybe? There was also that time after the divorce that I don’t remember when my mother says my suitcase and I waited at the front door for you to pick us up. You never came.

Perhaps you and your father were not as different as you had hoped.

It must have been strange for my mother to see me becoming so much like you despite your relative absence. Was it mostly nature or mostly whatever nurturing could be done on occasional Thursday evenings, and almost every other weekend? Whatever it was, I evolved myself from Eric Elie to L. Eric Elie to Lolis Eric Elie. My reasoning was simple. I can name a dozen Erics off the top of my head. Not so with our name.

I didn’t understand what it meant to be a single mother until I dated one. I realized something then. Being in the house with a child who needs or wants something is very different from fielding the occasional phone request. Making plans for an evening or weekend or month is very different when you have someone else raising your children.

You used to boast that you only spanked me once or twice when I was a child. Had you been at home after I turned eight, who knows whether that number would have grown.

***

The best we can do is teach our children to not make the mistakes that we made, teach them to extend and refine whatever legacy of progress we leave them. You progressed from Scotch and water to white zinfandel to Champagne. Still, when you were asked the vintage of that gift bottle of Dom Perignon you opened that time, your response was, “Vintage? It’s Dom Perignon, nigga!” I still smile when I think of that, but my taste in Champagne is more esoteric now. Perhaps your grandson’s palate will be so sophisticated that he’ll know the vintage of the wine without having to read the label.

You loved having flowers around, though you never had much patience for the work of gardening—the weeding and tilling and such. Maybe Niriko will learn to love caring for flowers as much as he loves the flowers themselves.

And if the family business is indeed something in the social services, maybe he will learn the arts of compromise and de-escalation, as neither you nor I managed to. Maybe he will temper his radicalism to be more practical; after all, the great American contribution to western philosophy is pragmatism.

When I moved back to New Orleans to write a column for the Times-Picayune, people would recognize my name and tell me they knew you from Dillard University, or the Dryades Street YMCA, or the courtroom, or the civil rights movement, or Mason’s Las Vegas Strip on South Claiborne Avenue. Perhaps the people who didn’t like you or respect you never bothered to speak of you to me. But those who did speak to me, without exception, spoke highly of you.

We don’t know much about the history of our name. You told me that your great grandmother, Mamie Jones, named your uncle after Lolis, a teacher who came to New Roads, Louisiana, our ancestral homeland. Uncle Lolis played trumpet and died mysteriously in Chicago. You never knew him. Then there was you, Lolis Edward, who begat me, Lolis Eric, who begat Lolis Niriko.

It’s a short history. Still, I hope that your grandson will come to realize that this name, our name, is an honorable name. A proud name. Who knows? Perhaps one day, like me, he’ll stop calling himself by his middle name and chose to cast his lot audibly with the Lolis Elies who have come before.