Music

Jason Isbell Picks a Legacy

The singer-songwriter—and actor—brings the heat on his forthcoming seventh album and cements his spot as the South’s reigning guitar god

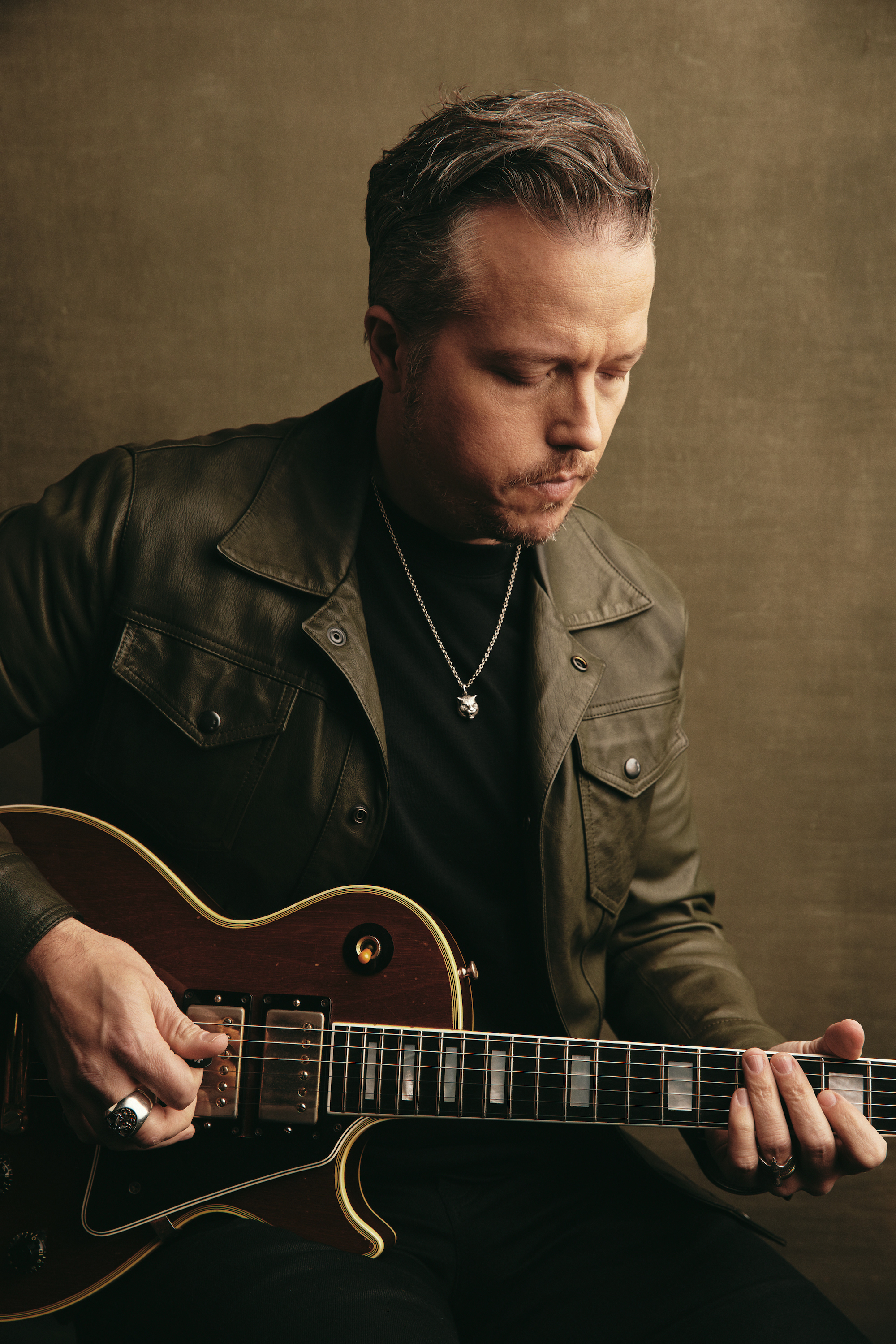

Photo: Robby Klein

Jason Isbell, photographed at the Mockingbird Theater in Franklin, Tennessee.

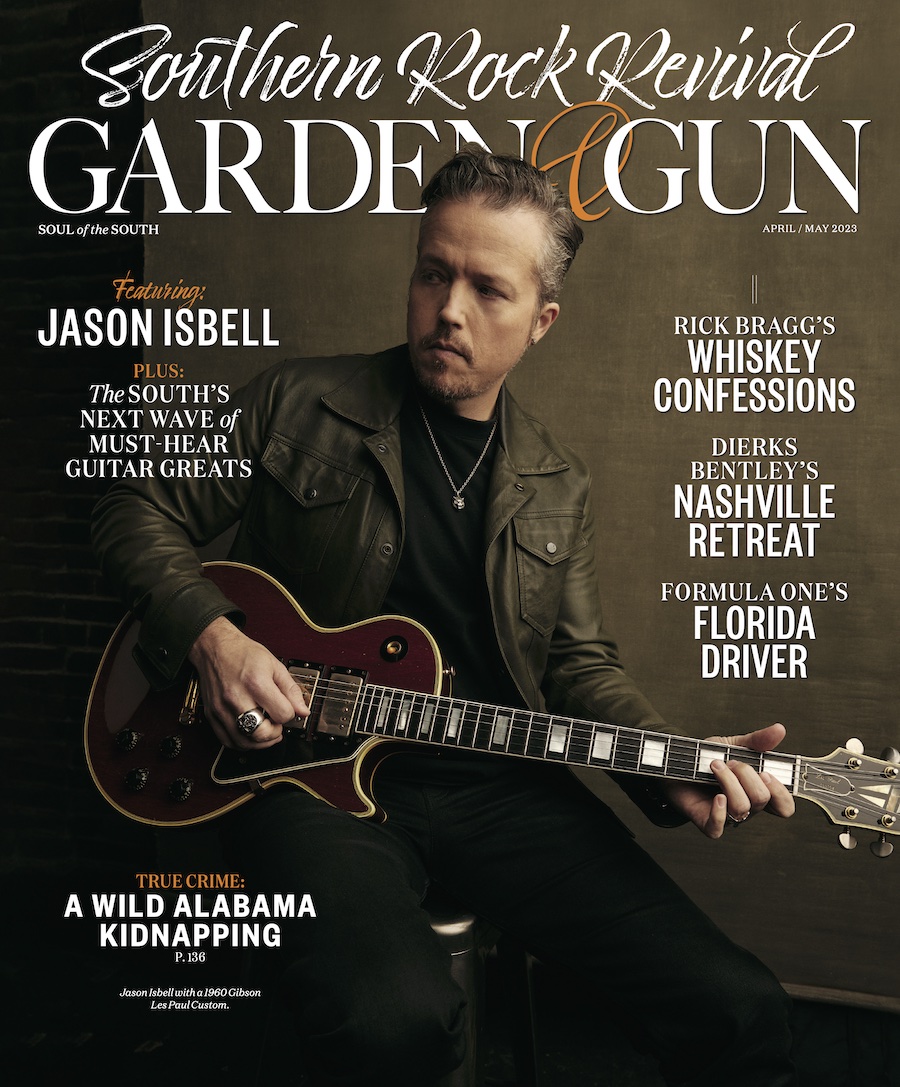

In January 2019, Jason Isbell got a call from Christie Carter, the owner of Carter Vintage Guitars, Nashville’s premier way station for collectible instruments. The shop had just gotten some new arrivals, and Carter wondered if Isbell might want to take a look. He went in the next day. He first played a 1973 Fender Stratocaster that Ed King—one-third of Lynyrd Skynyrd’s three-pronged guitar attack—used to write the lick on “Sweet Home Alabama.” Then he picked up a 1959 Gibson Les Paul that King had nicknamed Red Eye, a guitar with such notoriety that it was once stolen from him at gunpoint (then returned to him more than ten years later). Gibson had done a few collaborations with King, so Isbell wondered if the Red Eye was the real deal. It was. Skynyrd’s early seventies records—(Pronounced ‘Lĕh-‘nérd ‘Skin-‘nérd) and Second Helping—are seminal albums for Isbell. When he was eight years old, growing up outside of Muscle Shoals, Alabama, his uncle taught him to play the band’s classic “Simple Man” on an Electra MPC Les Paul copy. His uncle eventually gave him the guitar—which Isbell still has—and he played constantly, often even sleeping with it in bed next to him.

After leaving the store, Isbell called his business manager to see if he could afford it. No, he was told firmly. Then he called his longtime manager Traci Thomas and said he would do anything to buy it. Thomas talked to the business manager herself, called Isbell back, and said, “They could make it work.” It was his, for a price in the mid-six figures. To help pay the tab, Isbell played some gigs that he maybe wouldn’t have normally done. “I played a lot of parties, acoustic shows where Amanda came with me,” he says with a laugh. “On our anniversary, we played a private show for Viacom in Jackson Hole. It was weird shit like that.” It was worth it. Isbell says it’s the best-sounding electric guitar he’s ever heard. “It vibrates in a way where you can hear notes you don’t actually play,” he says. “You can tell that before you plug it in and how it feels against your body and in your hands. That one was alive.”

Wearing a denim shirt, black jeans, and vintage Adidas (he loves sneakers almost as much as guitars), Isbell is sitting at a table in the renovated barn on the property where he lives with his wife of ten years, Amanda Shires—a singer-songwriter and fiddle player—and their seven-year-old daughter, Mercy. An hour outside of Nashville, the barn is a veritable fun house of activity. There’s an art space with large abstract paintings on canvas created by Shires. There’s a rowing machine next to dumbbells, a resplendent daybed covered in a black-and-white polka-dot blanket and fluffy pink pillows, gig posters and other memorabilia, and a mini Ms. Pac-Man machine that Shires takes on her tour bus. “She’s really good at it,” Isbell says. The walls and ceiling are all painted black, and inside the bathroom is a handwritten note from Shires warning visitors not to “miss their mark” or else leave five dollars in a jar as a cleaning fee. There’s one bill in there. “Most likely from my dad,” Isbell says with a laugh.

On the west-facing wall sit the giant multicolored displays that Isbell has used as the backdrop for recent tours. There are of course a few guitars hanging on the wall, including a Flying V electric along with others that Isbell considers “new,” meaning they were built after 1970. He sometimes films his guitar-geek Instagram videos here in the barn. The Ed King guitar, however, he keeps locked up in a safe back at the house. There are multiple insurance riders on it, including one requiring Isbell to buy the guitar its own seat on airplanes. “I talked to Sharon [Ed King’s widow] and told her it wasn’t going to end up under glass somewhere,” he says. “I think she gave me a discount because she knew it was going to be used and not just looked at.”

Photo: Robby Klein

Isbell with one of his guitars, a 1960 Gibson Les Paul Custom with a rare cherry finish.

On the barn’s roof stands a metal weather vane with a cast-iron skillet on one end and a swallow laid over an anchor on the other, the logo of the band. Isbell had it fabricated at a shop in Atlanta. To him, the weather vane symbolizes change, a new direction. Weathervanes also happens to be the title of Jason Isbell and the 400 Unit’s seventh album (the weather vane itself appears on the cover), and the shift in vibe is palpable. After four albums with Nashville superproducer Dave Cobb, Isbell produced Weathervanes himself with one goal in mind: replicate the intensity and soulfulness of the band’s live shows. While previous records have leaned in to folkier singer-songwriter territory, Weathervanes, out in June, is a rock-and-roll explosion. Isbell and the band recorded it at Nashville’s Blackbird Studio in two weeks, staying true to their lean-and-mean recording process. Isbell plays the song a few times, the band members—bassist Jimbo Hart, guitarist Sadler Vaden, drummer Chad Gamble, and keyboardist Derry deBorja—figure out their parts, and then he hits record. The goal is two songs per day.

Isbell has long been known for his evocative, conversational lyrics, but anyone who’s seen him onstage knows his skills with a six-string rival his artistry with a pen. “Jason is a true triple threat, a world-class singer, songwriter, and guitar player—maybe the most threatening triple threat I’ve ever met,” says Patterson Hood, the front man for Southern rock stalwarts Drive-By Truckers, the band Isbell was a member of from 2001 to 2007. “He and I had an immediate and undeniable chemistry. I played him a song I had just written, and he played along with it as if he’d been playing it for years.”

Still, on Weathervanes Isbell is happy to share the spotlight with Vaden, who on previous efforts sometimes got lost in the mix. On the new material, Vaden is in lockstep with his bandleader. “We’ve never done any trade-off lead or harmony guitar on an album,” Vaden says, pointing to Weathervanes’ soaring finale, “Miles,” in which Isbell laments a disintegrating relationship between a man and his daughter. The song contains three distinct movements, with Isbell and Vaden building from a Neil Young–esque fuzz to a theatrical hard-rock midsection reminiscent of Queen before dissolving into a slice of Beatles psychedelia. “The disconnect between the way the records sound and the way we sound onstage didn’t really bother me,” Isbell says. “[But] it’s just a nice avenue to explore, as a lot of people are shocked when they see us live.”

Lyrically, Weathervanes is peak Isbell. There simply isn’t a more vivid, efficient songwriter in music today. “Did you ever catch her climbing on the rooftop / higher than a kite, dead of winter in a tank top / I don’t wanna fight with you baby, but I won’t leave you alone,” he sings in “Death Wish,” a pained look at a woman suffering from depression as the narrator wonders what—if anything— he can do to help. “Save the World” is perhaps the closest to a pop song Isbell has written to date, except it’s about the fear parents feel when they send a child to school in an era of mass shootings. Isbell admits it’s been a long process learning to balance the heavy, significant lyrics with the volume and bombast of a rock show without making it feel awkward or self-serving. “I’m homing in on the idea that you can have a lot of fun playing really sad songs,” he says. “That’s what the blues was. I’m not qualified to make blues music, but I can certainly take that spirit and knowledge and apply it to what I’m doing.”

Isbell began sketching out lyrics for Weathervanes while staying at an Airbnb in rural Oklahoma. He was there to film Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon, which is expected to be released later this year. Based on David Grann’s best-selling book, it’s the true story of the Osage Nation murders in the 1920s and Scorsese’s first stab at a Western. It stars Leonardo DiCaprio and Robert De Niro, with Isbell playing a significant role (as does his pal Sturgill Simpson, though they don’t have any scenes together). The shoot was grueling: eighteen-hour days, wearing heavy clothing in the Oklahoma heat.

“It was one of the most difficult things I have ever done,” Isbell says of his final, violent scene. “The pain was intense. The makeup guy started squirting fake blood directly on my eyeball. Every time they would call action, I’d have to pry my eyelid off my eyeball. I tried to sandbag it a bit during rehearsals, but Marty said, ‘You’re on pain level ten. You’re feeling all of this. Please dial it up.’ So I was like, ‘Oh, shit. I’ve got to really scream.’”

Isbell, who loved watching Westerns with his grandfather when he was growing up, had a little prior acting experience, playing bit parts in the television series Billions and the Deadwood movie, but when touring ground to a halt in 2020 due to the pandemic, he began exploring possible film roles. Scorsese’s casting director happened to be a fan, and shortly thereafter, Isbell found himself doing Zoom readings with DiCaprio while Scorsese watched. “Neither of them gave me any feedback,” he recalls. “But then Marty starts talking about how he did things on his other films, so I’m thinking I at least have a shot if he’s telling me this stuff.” Later that afternoon, he offered him the part.

Isbell doubts he’ll do something like that again, because it took him away from Shires and Mercy for lengthy stretches of time. But he did pick up a few things from the director that helped him to make Weathervanes on his own.

“What I saw through Marty is that if you have the right people in the room, you don’t have to micromanage,” he says. “But if something needs to be done, you should do it yourself. One day, I saw him get out of his chair, walk over, and fix a man’s jacket in the middle of our shot. It’s ninety-five degrees and everyone’s wearing tweed, and he just walks across the field and comes over and grabs the man’s jacket, pulls it and pats it down and then goes back and sits down at his monitor.”

Killers of the Flower Moon isn’t the only screen time for Isbell this year. During the making of his 2020 album, Reunions, a camera crew followed him around constantly, filming for the HBO documentary Running with Our Eyes Closed, the title taken from a song on the album. The film offers a deeper look into his personal life than he typically reveals, including his marriage to Shires. There’s a moment when it seems as if everything is going off the rails. A snotty remark spirals downward into days of soul-searching, sleepless nights, and lengthy text messages. Because they live together, sometimes work together, and have a beautiful daughter, there’s often a perception by fans that their family life is effortless. The documentary shows that, unsurprisingly, it takes heavy lifting. “It is so easy to have misperceptions about someone’s life when we don’t know them,” says the director, Sam Jones. “The idea was to put the audience right in the center of a person’s life and see what it really is. He and Amanda were willing to show that.”

It’s a cringey watch at times. Isbell can be moody and, despite his commanding stage presence and witty Twitter posts, sometimes racked with self-doubt. Shires often bears the brunt of trying to convince him that he doesn’t have to stew on things alone. “I came from a culture where if you’re the man of the house, you fix things,” he says. “It’s another thing to view your spouse as an equal. You know, it’s that ability to not take every responsibility as yours to fix. But it’s hard to let go of those things and say, This is wrong, and it might stay wrong, but I’m here and I see that it’s wrong.”

Isbell says that many of their friends got divorced during the pandemic, but ironically it may have been the best thing for his own marriage because it forced him and Shires to have those difficult conversations and clear the air. And it ultimately helped to distill what’s truly important to him. “I arrange my day based on two things: When am I going to hang out with Mercy? And then when am I gonna get to play guitar?” he says. “I never wanted to be a firefighter, or an astronaut, or any of that boy stuff. I honestly don’t remember a time when I didn’t dream of being a guitar player.”

See the South’s Hottest Guitar Heroes