On Sunday nights in the nineties, locals from northern Mississippi’s hills and hollers, and sometimes a handful of adventurous tourists, gathered at Junior’s, an hour’s drive from Memphis in one of the South’s most unforgivingly rural landscapes. Inside, the revelers sipped moonshine from glass jars and danced as trancelike jams led by the now-legendary bluesmen Junior Kimbrough and R. L. Burnside stretched into the early morning hours.

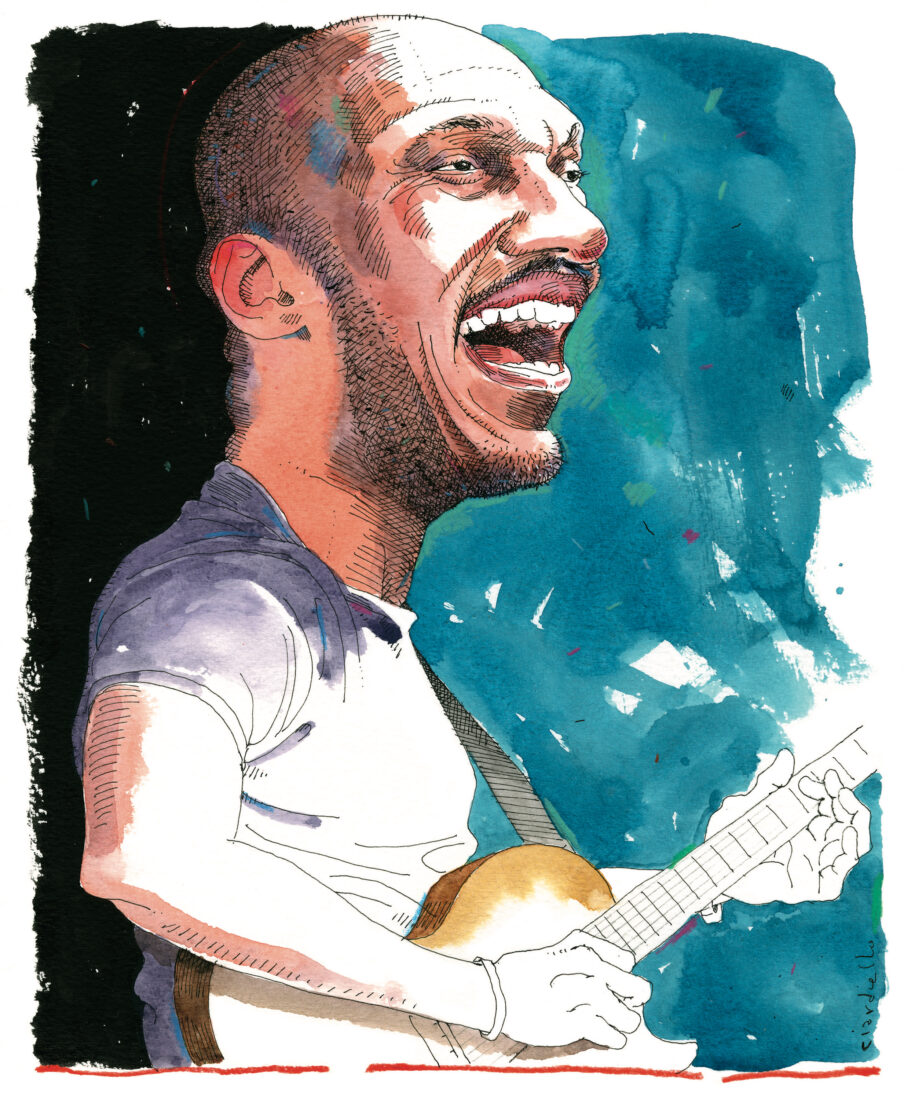

Forty-four-year-old Cedric Burnside, a grandson of R. L.’s and now a Grammy-winning artist, grew up in this world. “By age ten, I was [playing] at the juke joint,” he says, “and I was about thirteen years old when I joined [R. L.’s] band full-time.”

While he’s known today for his own interpretations of the Hill Country blues style his grandfather helped create, at the time Cedric played drums behind R. L., providing the rhythmic foundation for excursions on regional standards like “Goin’ Down South,” “Shake ’Em On Down,” and “Poor Black Mattie.” But he also kept a close watch on what his “big daddy” was doing on guitar and how he communicated with his audience—lessons Cedric bookmarked for the music he began making after R. L.’s passing in 2005.

Watch G&G‘s Back Porch Session with Burnside:

Like his grandfather, Cedric uses his fingers to pick as he glides seamlessly between acoustic and electric guitar, channeling a raw, rural, and hypnotic blues. But while his sense of rhythm and swing are classic Hill Country, his ear for melody has a wide aperture, absorbing a broad range of influences that inject new energy into the canon. On a trio of recent albums—Descendants of Hill Country (2015), Benton County Relic (2018), and I Be Trying (2021)—he has evolved into the most potent contemporary practitioner of the tradition. We caught up with Burnside to talk about growing up in the jukes, picking up the guitar, and the inspirations behind his own soulful take on Hill Country blues.

You grew up in a legendary musical family. Did it feel that way at the time?

As a kid, I thought it was just something normal. My big daddy [R. L.] and my dad [Calvin Jackson] and uncles, they played every other weekend. I was one of many grandchildren, just amazed by the music and out there kicking up dust. My late teens is when I started to realize how special this music was and that it was history. And that it was gonna make more history.

That must have been at Junior’s, right?

It started at our house before Junior’s juke joint. My big daddy was having house parties at the little shack we were staying in. People would come from miles around just to hear the music, and shortly after that I started going to Junior’s. Going to the juke joint at ten years old was pretty wild, and kind of scary and fun at the same time. Because even though I was young, I did know that it was a juke joint and people drank moonshine and other things there, and it was a place young kids shouldn’t be. But I guess [since] we was playing the music, if they sent us home, then they didn’t have no band. So they made an exception and let us stay.

You had a front-row seat for the Hill Country revival that took off in the nineties.

That was definitely a change for me. At the juke joint, the crowd was the same every weekend. So when I went to Canada, my first time out of the country, I had butterflies because I didn’t know how they would receive the music we play. My big daddy’d say, “No no no no, just do what you do at the juke joint and everything gonna be good. Don’t change nothing.” Then we did the first song, and people was jumping up, clapping and whistling, and it was a beautiful, beautiful feeling. All the butterflies went away, and I was ready to lay it down.

What was it like being around R. L. in those days?

He had this aura about him that was so bright. He was my grandfather and I grew up with him, so you would think that I would be used to watching him play music, but it was so different watching him onstage do his thing and watching the audience look at him. I find myself today wanting to have that same energy, that same aura when I go up there and play my music. He gave it his all and that showed, so I try to give it my all when I play. And hopefully it shows to people.

You played drums then. How did you find your way on guitar?

I always knew it was in me. I wrote a lot of my songs [by] sounding them out with my mouth, how I wanted the music to go. But I picked up the guitar for the first time around 2003 and started trying to get serious about that. I got tired of sounding things out with my mouth. The guitar players would get as close as they could, which was great, the song still came out good—but it wasn’t what I heard in my head.

Once you set out on your own, you were pretty successful right away. Did it catch you off guard?

I know my music is different from any other blues you would probably listen to, and for that I am grateful. I like to be different. Having all the accolades and all the awards, it made me feel real good about my accomplishments [and] the hard work I put in to get where I am today. When I started writing my own music, playing my own guitar, people caught hold of it. They started liking my lyrics and my grooves, and I knew then, even before the Grammys, even before the National Endowment [for the Arts, which named him a National Heritage Fellow in 2021], I knew that I had something special. I do it because I love it and it’s in my heart, and I knew if I kept on the right track and didn’t let anybody interfere, it could only get greater from there.

Some Hill Country music can have an ominous feel to it, but your songs have a different vibe.

I try to write my music according to how I live my life and according to how my family lives their life. We all go through things, and I think every day we wake up, the universe is gonna give us something to write about. That might be good, that might be bad—sad things, confusing things—and the universe does that for me every day of my life. Some days I wake up and great things happen, but you got to accept the bad things, as well. I think the key to my music is staying true to myself. Even if it’s embarrassing, even if it’s nerve-racking, I still write about it. I know somewhere out there in the world, somebody’s been there and done that. That experience made them come from the bottom to the top, or that experience made them fall from the top to the bottom.

Junior’s is long gone. Where is that spirit of Hill Country music most alive today?

Well, they can definitely come to Cedric Burnside’s front porch. [Laughs.] You still have juke joints in Mississippi, but in North Mississippi there’s not too many left. My wife and I did just purchase thirty-seven acres in Ashland, the town we stay in, and sometime in the future I am planning on putting something out there to maybe sell a little food, just like Junior Kimbrough’s juke joint used to do. A few chicken wings or a few bologna sandwiches, have a few beers and listen to some Hill Country blues. So I’m planning on doing that in the near future, the good Lord willing.

So as Tyler Childers sang in “Country Squire,” you’re “turnin’ them songs into two-by-fours.”

My music is something that I want to keep alive, and the Hill Country blues is really special and unique. I want people from all over the world to come and experience that feeling, not just [me] going to their country and playing it. I love doing that, but I want them to also come into my world, come into the Hill Country world, the heart of Mississippi, and feel that music and sweat and see the mosquitoes flying all around your head while you’re stomping your feet and kicking up dust.

See the South’s Hottest Guitar Heroes