Land & Conservation

The Longleaf Pine

Rebuilding the fireforest of the Old South

Photo: Andrew Kornylak

Richard Porcher walks me out to the edge of a parcel of his land near Manning, South Carolina. It’s a bright July morning, and he is dressed in faded seersucker pants tucked into knee-high waders. A floppy hat sits atop a swatch of white hair. He speaks in a Charleston accent so old school that the air practically wafts with traces of wisteria and Japanese plum.

He sweeps his walking stick across the field, proud to show me these fifty acres, even though they could not look more bombed-out, clear-cut, and beat-up. Chunks of graying splintered trees lie about on sandy soil. Dead hickory saplings wilt beneath crisp leaves, and other throttled hardwoods crumple into black thickets. Here and there a single oak stands isolated in the dusty air like a child’s cartoon sketch of a tree. The place could pass for the outskirts of Baghdad.

“We sprayed to kill the hickory and the oak but it didn’t work,” he says, and pokes his stick into some audacious green brush. “These will branch up quickly and we’ll be right back where we started from, so they’ll have to spray again this fall.”

Photo: Andrew Kornylak

A skyward view of a young planted longleaf pine forest in Francis Marion National Forest.

Porcher winces at talk of chemicals. He is a retired professor of biology at the Citadel and coauthor of the definitive text A Guide to Wildflowers in South Carolina. He wishes there were some other way, but he knows that an ancient environmental battle is being waged here between new terrains — hardwood forests, cotton fields, other farm land uses, pulp-paper pine crops — and the primordial longleaf pine woods that flourished here for millions of years. The only way to win, on this particular acreage, is to strip the old slash pine forest that previously stood here to the bare canvas of the underlying soil and start anew. The price is high, Porcher confesses, but insists it will be worth it. A generation from now, when others stand here, they will be looking into an unusual woodland — the original landscape of much of the Old South: a longleaf pine forest that flourishes by catching on fire every year.

To any American who knows by rote that “only you can prevent forest fires,” this single fact sounds preposterous. Yet, if the tropics can boast the rainforest, which needs constant and heavy downpours, then the Southeastern United States can claim what has been called the “fireforest,” which needs an annual low-intensity pine-straw fire to jump-start the mysterious mechanics of its woodlands and nurse a stunning diversity of wildlife comparable to that found in the Amazon.

Now, thousands of Southern landowners like Porcher are actively engaged in this restoration, and part of the motivation is ecological: Native wildlife flourish best under the longleaf’s sun-welcoming canopy. Part of it, though, is historical, even spiritual, as many Southerners return the land to its antebellum pristine condition. But part of the changeover is due to a handful of devotees at organizations such as the Longleaf Alliance and Tall Timbers. In the past two decades, they have pulled off an amazing feat: convincing landowners of the value of fire; sussing out the science of planting the finicky longleaf seedlings in the soil; and politicking the government into encouraging this hard work. As a result, today’s landowners luxuriate in a host of government subsidies — cost-sharing plans to kill off the invasive hardwoods, support to seed the longleaf’s understory, as well as outright payments to maintain longleaf forests until they get established again. Rather than continue to squeeze depleted farmlands, now landowners can make money by turning over spent cotton fields and exhausted pastures to longleaf.

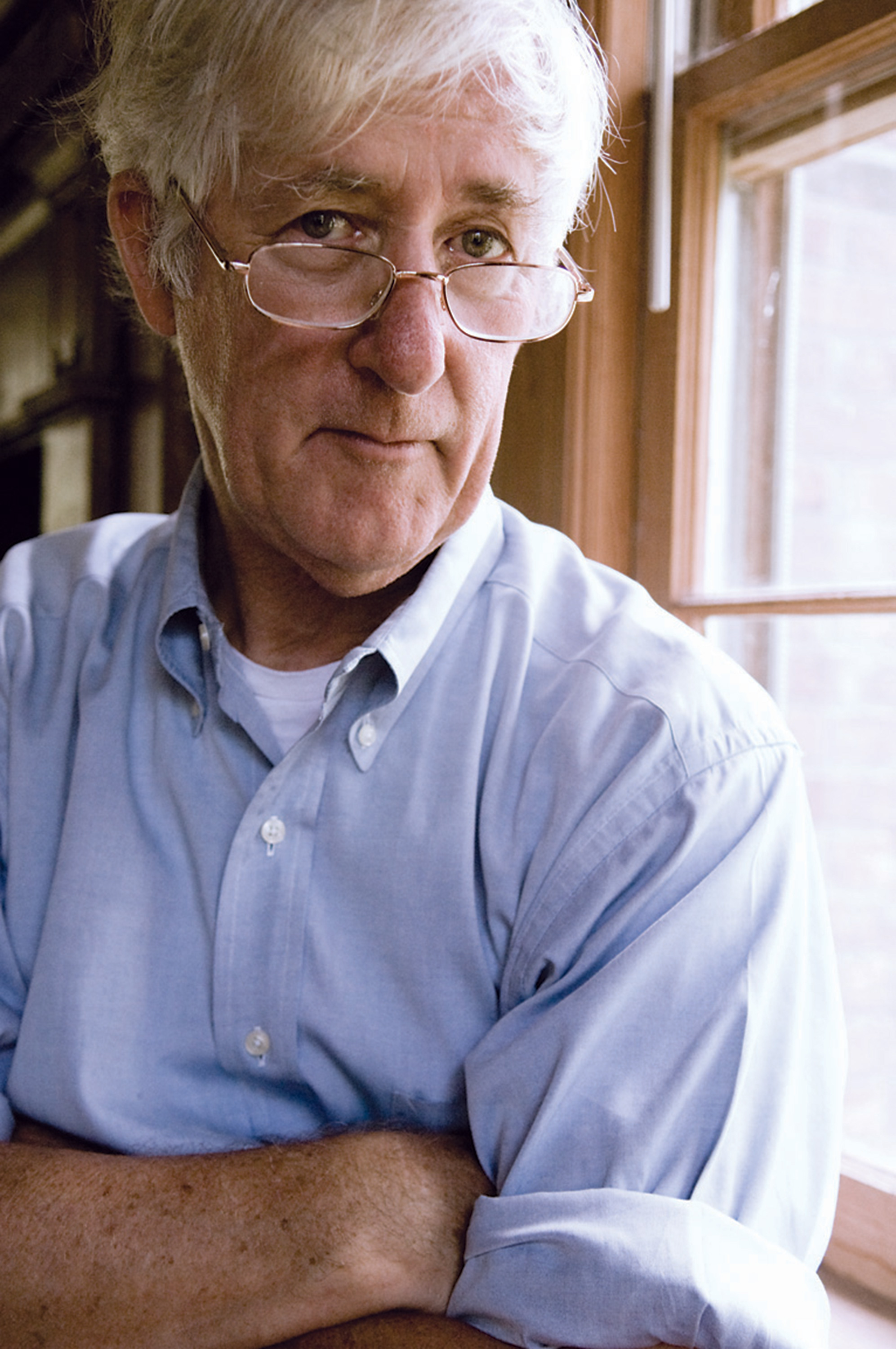

Photo: Andrew Kornylak

Botanist and landowner Richard Porcher is among the emerging fireforest evangelists who argue for the restoration of this original woodland that once defined the Southern landscape.

Their success recently became measurable, according to Dean Gjerstad, codirector of the Longleaf Alliance at Auburn University’s School of Forestry. In 2005, there was an increase of 604,386 acres of longleaf planted by private landowners and another increase of 303,320 acres on public lands. It’s been a long time coming: That’s the first recorded increase in overall longleaf acreage since the forest’s precipitous decline began in the years after the Civil War.

For many Southerners, the “forest” is what they see just off the interstate: dense hardwood thickets or row-planted loblollies that flicker past like a picket fence. They are no longer familiar with the sublime beauty of a longleaf forest, with its low ground cover that rises not much more than a foot or eighteen inches, opening up to an airy mid-story creating sunny, prairie-like vistas through ramrod-straight longleaf poles. Nor do they know the largely hidden history of its ghastly holocaust a century ago, a nightmare tale of ignorance, greed, and desperation.

The longleaf pine ecosystem used to stretch from Virginia south to Florida’s Panhandle and west to Texas, arguably the largest single-species forest ecosystem in the world. Once covering ninety million acres, longleaf defined the Old South. Some early naturalists looked upon the longleaf in awe, as riders on horseback could gallop through it effortlessly for hours. Other writers were baffled by it. Mark Twain’s neighbor, Harriet Beecher Stowe, descended from her Connecticut pulpit to opine on the South’s slacker landscape in her (now) comically ill-informed book, Palmetto Leaves. She came and saw the “tall pinetrees, whose tops are so far in the air that they seem to cast no shade, and a little scrubby underbrush.”

Photo: Andrew Kornylak

Porcher tours his longleaf pine plantation near Manning, South Carolina, explaining the dynamics of the fireforest ecosystem.

Where others might see a simple difference and appreciate it, Stowe, like some antebellum talk-radio host, saw nothing but hideous moral corruption everywhere.

“In New England,” she wrote, “Nature is an up-and-down, smart, decisive house-mother, that has her times and seasons… She will have no shilly-shally.”

But below the Mason-Dixon? Why, nonstop shilly-shally: “Nature down here is an easy, demoralized, indulgent old grandmother, who has no particular time for any thing, and does every thing when she happens to feel like it.” For Stowe, the longleaf corrupted Southerners into muddled idlers. After “everybody up North has put away summer clothes, and put all their establishments under winter-orders,” she concluded, Southerners were still staggering around their pine forests in December, wondering: “Is it winter, or isn’t it?”

And yet, private landowners like Porcher are willing to sacrifice their virtue to restore this landscape. In fact, they love it. Walking the land with Porcher is a leisurely all-day affair because there isn’t a tree or plant that he can’t talk about. “Every plant has a story,” he says. When I bend down to touch an unusual plant, he tells me: “That’s gummo root, supposed to be an aphrodisiac, if you chew it, according to the rural people of South Carolina.” His eyes begin to smile. “It doesn’t work,” he observes.

Photo: Andrew Kornylak

Wire grass and other ground cover sway in the breeze in the longleaf pine ecosystem of the Wade Tract Preserve near Thomasville, Georgia, a 200-acre old-growth research plot managed by the Tall Timbers Research Station. The Wade Tract is one of a very few old-growth stands that have been managed with fire for decades.

At another spot, where the land is further along, the longleaf seedlings, like Roman candles in the ground shooting off green pyrotechnics, are arrayed amid other green shoots cracking the charred surface of a recent burn.

“Here is Stipulicida, wire plant,” he says, plucking a stalk as thin as a needle. “This is all your ground cover. That’s climbing butterfly pea, and here’s Desmodium, or beggar’s-lice. This is sweet goldenrod.”

Of course, he can talk this way because he’s a botanist, but here’s the deal: Hang around enough longleaf enthusiasts and you realize they all talk like Porcher, and they can’t wait to tell you about the fireforest’s diverse ground cover. Retired Auburn professor Rhett Johnson refers to such people, and he includes himself, as “longleaf pimps.”

Once covering ninety million acres, longleaf defined the Old South.

What makes them so eager to entertain you with their version of “Pimp My Dirt” is that the complex environmental mechanics of the longleaf forest are in fact pretty cool, and once you get a sense of how all the (very slowly) moving parts work, it’s impossible not to want to explain it to somebody. You get the sense that they’re writing their own Disney movie, featuring any of the potential protagonists, our wily longleaf friends: the fox squirrel, bobwhite quail, gopher tortoise, harvest mouse, indigo snake, wild turkey, and red-cockaded woodpecker.

In the opening drama of the movie, the critters are at play in their sunny cathedral-like piney woods until they realize that invaders have come, and not just predators: Even in their midst, alien trees such as the oak and persimmon and hickory trees are sending up shoots. The conflict is clear. The invaders want a shady damp forest. They intend to remake the place into a dark forest that Little Red Riding Hood would recognize (a morally correct Harriet Beecher Stowe forest).

What to do? In a last-ditch effort, they turn to the ancient longleafs. The towering senator trees preach patience, telling everyone to wait for the summer to get just a little hotter. Then, in the climactic (and climatic) scene, an August thunderstorm erupts. The outsiders get spooked when bolts of lightning ignite the dead longleaf needles and brown wire grass blanketing the forest floor. The resin in that mix is so flammable that they can burn even in the rain. The outsiders flee, and the fire burns the hardwoods and other competitive pines to the ground. The highly fireproofed longleafs practically yawn through a nice cozy burn.

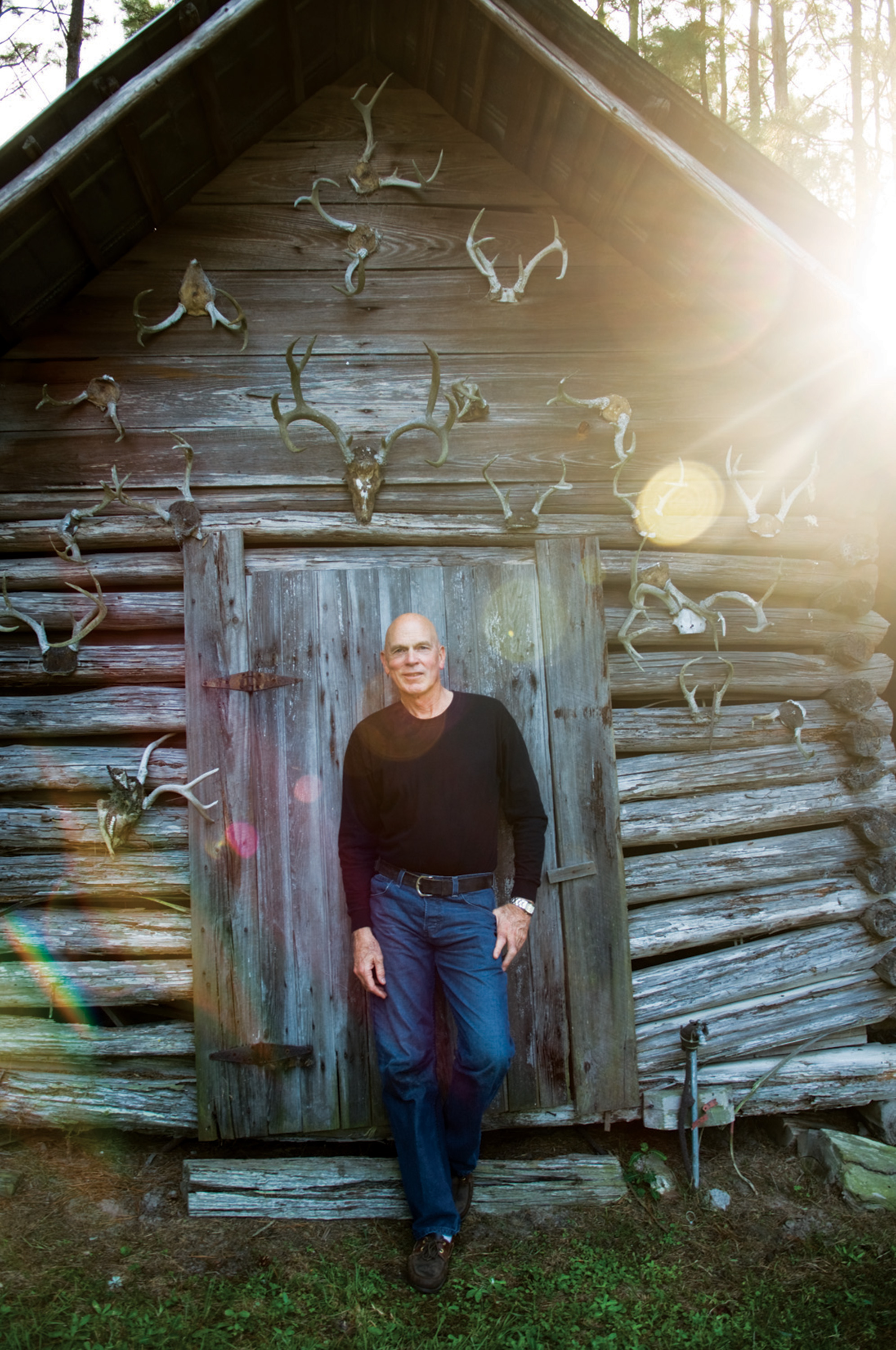

Photo: Andrew Kornylak

South Carolina orthodontist Skeet Burris stands in front of an old barn on his plantation near Cummings, South Carolina. Burns replants played-out farmland to restore the ancestral forest of the Old South.

Meanwhile, the longleaf critters recall that they can sense the fire quicker than others, and that in some parts of the fireforest they have fallout shelters, like the gopher tortoise’s burrow. Running some fifteen to thirty feet in length, these holes have been found by longleaf scientists to provide temporary shelter for more than three hundred species, including snakes and mice and some other fairly sizeable animals.

And when it’s over, everyone returns just in time for all those legumes and seeds and tasty ground cover, also adapted to fire, to poke right back up. In a fireforest, the intense diversity is not in the canopy, as it is in the rainforest, but on the ground. Scientists have counted as many as forty species flourishing in a single square yard of healthy longleaf ground cover.

It all might seem like a cartoon now, but understanding how this system works has been a long time coming — and the misunderstanding of it lies at the root of the longleaf’s decline. For much of the twentieth century, federal forest agents heard about the old custom of burning the land, but simply refused to give any credibility to the local argument that fire might be beneficial. In the 1920s, a group called the Dixie Crusaders traveled around, showing films and giving talks, preaching the evil of fire. Later, Smokey Bear took up the same sermon far more effectively.

Photo: Andrew Kornylak

Burris walks in a stand of young longleaf pines that he planted on his property.

Fire suppression made sense in some parts of America, but as the new rule in the South, the oaks and the hickories and the sweet gum seized their advantage, shading out the longleaf and driving off the luxurious wildlife food found in the ground cover. Otherwise, the land got planted over in slash or loblolly, which had a shorter rotation and were more easily marketed as pulp, chip-and-saw wood, or pole timber. Longleaf critters also began to experience massive population declines. The bobwhite quail has plunged some 90 percent in the past few decades.

In the era before World War II, though, a forester and scientist named Herbert Stoddard began to make the case that the folklore was right: Smoldering ground fires were good for the land. Later he hired a young kid named Leon Neel, who still preaches the benefits of fire in northern Florida, one of the original longleaf pimps inspiring the current generation to assist the longleaf to regain its natural advantage.

“See, the seed bank is still here in the soil,” Porcher tells me, poking at the ground with his stick. “Once I cleared it of hardwoods and started burning, these plants popped right back up.” It’s as if the longleaf ecosystem were hiding in these hardwood forests, waiting patiently for us. Yet, fire suppression continues to be practiced in much of the South. It allows dried needles and fallen timber to accumulate into a natural ammo dump that will eventually explode into a massive forest conflagration, killing everything.

Photo: Andrew Kornylak

Walter Sedgwick's family home at the Millpond Plantation near Thomasville, Georgia.

That is precisely what happened in 2007 when the Bugaboo Scrub Fire in Florida merged with Georgia’s Big Turnaround Complex Fire. Cumulatively they burned more than 564,000 acres, and Georgia’s portion of that fire is, to date, that state’s largest recorded fire.

Just outside Thomasville, Georgia, are the millpond Plantation and other Wade family lands totaling some ten thousand acres. Nestled within them is a two-hundred-acre wood called the Wade Tract Preserve, among the most studied parcels of land in the United States.

“Each tree is numbered,” explains Walter Sedgwick, a family member who’s invited me to walk the land. “Their condition is tracked by computer.” This modest parcel is the largest tract of virgin fireforest remaining in the South. Do the wretched math: 0.000002 percent of the original ninety million acres.

Photo: Andrew Kornylak

Porcher looks over the vegetation at his longleaf pine plantation. There is not a plant he can't talk about.

“You could not devise a federal program to be that efficient,” Sedgwick says. The story of the longleaf’s destruction is not just a parable of market efficiency. It is also one of the hidden histories of the South. Beginning in roughly 1880, speculators saw the easiest business opportunity in the history of the world: ninety million acres of the most beautiful pine on earth, and, living right on top of it, a desperate, starving labor force.

There was even a book published in 1880 called How to Grow Rich in the South, written by W. H. Harrison, Jr., who was either the grandson of the president by that name, or a man who permitted people to think so. I bought an original copy off the Internet, and it is a breathtaking read.

The chapters have names such as “Cattle” and “Duck,” breaking the South down into every exploitable commodity no matter how small. There are chapters called “Beans, Snap” and “Cabbages, Early,” and on down to the last chapter on timber. The book encourages speculators to hurry because “the lumbermen of the North are buying up large tracts of valuable timber lands and putting in saw-mills.” Land in the South, Harrison tells his eager readers, that “is now for sale at $1 to $3 an acre will bring $50 to $100 within twenty years, for its timber. Southern timber land is an absolute certainty as a profitable investment.”

Photo: Andrew Kornylak

Mature longleaf pines tower over young pines and seedlings at the Millpond Plantation.

And the speculators descended, and the timber companies also came, buying up land in 100,000-acre dollops. One can argue about the dates but, effectively, between 1880 and 1920 the eleven states of the Old South were clear-cut into a confederacy of muddy stumps. The loggers were sloppy, wasteful, and reckless. In the slang of the day, they “cut out and got out.” Rivers churned with what looked like melting sludge of hills dissolving into plains. Ghost towns appeared after an area was “sawed out.” The mountains of sawdust left behind often would catch fire from lightning and smolder for years.

The devastation was so extensive that state revenues dropped as taxable forest property had to be reclassified as nontaxable wasteland, thus extending the economic crisis of 1865 into an eighty-year catastrophe.

Other economies eventually arrived, such as planting over the old longleaf soils with loblolly and slash pine to feed the paper mills. With that, the shame of this massive clear-cut receded into history, largely without leaving one.

Walking the land with Sedgwick you are amid thousands upon thousands of acres of some of the finest second-growth longleaf there is. Almost all of his acreage is naturally regenerated. There are old trees and young. He burns regularly. The wildlife is abundant. For several days we come upon countless tortoise burrows and the telltale nesting cavity of the red-cockaded woodpeckers some sixty feet up a mature longleaf. The Disney plot line is easy to follow in Sedgwick’s woodlands, in part because he manages the full landscape with an eye toward upping the quail population. He hunts them.

As the scientists see it, the road back from longleaf extinction began with accepting the phoenix-like powers of fire and rediscovering just how nature worked out these tradeoffs several thousand years ago.

This is controversial, but not because of the hunting: Some conservationists argue that managing the land strictly for quail alters the character of the forest. Here, the resurgence of longleaf is not a fundamental question about converting the land or not, but a nuanced philosophical issue about how to garden a forest. What should the focus of the land be — the trees? The quail? The woodpecker? The fragile orchids? The diverse ground cover?

“The question is, is there a happy medium, and I think there is,” says Sedgwick, who was instrumental in changing the way this argument has occurred, from one based in natural history (which relies upon keen observation) to one based in empiricism (which relies upon experimentation). Georgia’s longleaf group, Tall Timbers, was more natural history-based when Sedgwick joined the board.

“In a Putney Swope moment, I was elected chair,” he explains. (Putney Swope is a 1969 movie about a black guy who accidentally gets elected chairman of a company and revolutionizes it.) Soon thereafter, Tall Timbers shifted from viewing nature as an observation made by elegant elders to a science that sought empirical proof.

Photo: Andrew Kornylak

Jim Cox, an ornithologist with the Tall Timbers Research Station, working on the Wade Tract Preserve. He monitors bird populations on the longleaf pine tract.

“For example, natural history would look at the quail living in the thickets of the loblolly and think they needed thickets,” says Tall Timbers game bird specialist Bill Palmer. “But that turns out not to be true.” In fact the open grasses of the longleaf provide plenty of cover for quail. Moreover, because of the fire-resistant properties of longleaf ground cover, says Palmer, scientific studies have now proven that the bracken ferns, legumes, and perennials turn out to be a consistent food source for quail even in hard times.

“On the Wade Tract this year, we had radio collars on the birds,” says Palmer. “We had severe drought near where nesting occurred, but brooding was going on regardless in the longleaf. On the old field sites, brooding was severely delayed because the plant community response there was so slow due to the drought.” As the scientists see it, the road back from longleaf extinction began with accepting the phoenix-like powers of fire and rediscovering just how nature worked out these tradeoffs several thousand years ago. And there’s been modest progress ever since.

Just past the liquor store in Cummings, South Carolina, if you head out Bubba’s Road, you’ll eventually get to Cypress Bay Plantation, owned by Lowcountry orthodontist Skeet Burris. An avenue of young oaks leads you to a brand-new house made of old-looking brick. Off to the side of the house is a small waterfall gushing into a little swimming hole surrounded by banana trees and elephant’s ears before sluicing into eleven acres of lake and cypress swamp. An osprey flies over and lands on a cypress branch. A black lab runs up. “Here, Boone,” coos Burris. Towering pines in the far distance complete the tableau. It’s a postcard-perfect Lowcountry plantation scene. “Everything you see here,” Burris says, “I planted.”

Photo: Andrew Kornylak

The Wade Tract is one of the most studied parcels of land in the country. Each one of its longleaf pines is numbered and its condition tracked.

Burris dug the swamp himself and planted the cypress. Much of his pine forest grows on clear-cut fields and played-out farmland purchased in the last ten to twenty years. As Burris takes you on a tour of his twenty-six hundred acres, you learn just how gardenable the pine forests and low-lying wetlands are.

After moving into South Carolina from Tennessee in the 1970s and opening his dental practice, he got invited to some of the older plantations. Nemours Plantation. Good Hope Plantation. There he saw what an elegant Southern landscape, particularly a mature cathedral pine forest, looked like. So when he first bought land twenty years ago, he started gardening the upland to look like the ancestral forests he’d seen. While there were some bits of timber on his land, Burris’s work is proof of just how much can get done, in a comparatively short amount of time, even on cutover land.

Where does this impulse come from? Judd Brooke in Mississippi knows. He watched the loblolly sections of his four thousand acres get massacred by Hurricane Katrina in 2005, while the longleaf fared a lot better. The longleaf is also more resistant to various beetles and fungi, not to mention fire. Brooke is now planting longleaf wherever loblolly and other pines stood — but not only for its hardiness.

New landowners and old might manage the forest for quail or trees, woodpeckers or pitcher plants. Still, the draw for all of them is to be able to look into a forest that once, a long time ago, did stand right there. Maybe the South will rise again.

“I just put in two new roads on my place, and I followed the old railroad dummy lines from the 1920s when the last virgin timber was logged,” says Brooke. “I was just sitting and thinking about why that railroad line was there. They used teams of oxen. The railroad line followed the foot of the hills because it’s easier for the oxen to pull the log downhill to the train. The railroad line is more level and there’s hardly any rise or fall in the road. You look at that and you get a big sense that you are getting things back to where they were originally. There’s a lot of history in these woods.”

Aesthetics and history. New landowners and old might manage the forest for quail or trees, woodpeckers or pitcher plants. Still, the draw for all of them is to be able to look into a forest that once, a long time ago, did stand right there. Maybe the South will rise again.

“If I couldn’t sell my longleaf that would be fine,” says Brooke. “I could just look at them.”

For this generation, it would appear that longleaf has turned the corner. Yet even as the old crop fields get converted, longleaf pimps such as Rhett Johnson already observe another crucial economic shift that will figure prominently in the next round of restoration. As the era of the paper mill comes to an end, big companies such as International Paper, Georgia-Pacific, and MeadWestvaco are selling off their massive holdings of timberland and moving to countries where paper timber is cheaper. Some of the land they are selling is being bought by individual landowners, but the overwhelming majority, according to Johnson, is getting locked up in investment vehicles called TIMOs — Timber Investment Management Organizations.

Photo: Andrew Kornylak

Mature longleaf pines stand undisturbed at the Wade Tract Preserve.

According to a Yale School of Forestry study, some eighteen million acres of forest were in TIMOs by 2002. Together with some three and a half million acres of longleaf parcels quilted across the South that Southerners fought to save after the original clear-cutting — which is now concentrated in revered parks such as Apalachicola, Francis Marion National Forest, and Kisatchie — the holdings in TIMOs could go a long way toward accelerating the return of a primeval forest. But many TIMOs are pension funds — instruments designed to extract the maximum profit — and it’s not at all clear what will happen with this new bulk of land.

When those TIMOs come due and have to deliver major returns for their investors, the future of much of Southern woodlands may well be, once again, out of Southerners’ hands. In fact, it may depend more on how a group of Indonesian investors decide to cash out, or the mood of Californians when they plan to retire.

“I think they will eventually be forced to sell this land, and the buyers won’t have a market for the wood,” says Johnson. The departure of the mills will mean that the transportation costs for timber might make even tree farming prohibitive for the next generation. “I’m afraid a lot of that land will be developed.”

It’s almost as if someone were updating How to Grow Rich in the South, except the last chapter on timber can’t be read for another generation. Then we’ll see if our grandchildren are hunting quail in the fireforest of our ancestors, or kicking back in their time-share next to the golf course at “Longleaf Acres.”