Arts & Culture

The Lost Pilot

Paul Redfern disappeared more than ninety years ago. His fate remains a mystery

On August 25, 1927, pilot Paul Redfern took off in a single-engine monoplane from Sea Island, Georgia, bound for Rio de Janeiro, hoping to capitalize on Charles Lindbergh’s recent success in making aviation history.

Instead he flew into a mystery that has spanned most of the last century and into this one, and however commendable his quest was, Redfern seemed to have less in common with Lindbergh than he did with “Wrong Way” Corrigan—the aviator who famously took off from New York headed for California, and instead wound up in Ireland.

Redfern’s adventure was extremely ambitious, not the least because Rio de Janeiro is a thousand miles farther from the United States than Lindbergh’s Paris, which brought its own set of problems—namely, how to carry that much more gasoline, when Lindbergh himself had chewed the very edges off his charts to save a few kilograms of fuel weight.

Aviation at the time was barely out of its infancy, which began in 1903 when the Wright Brothers’ self-propelled airplane first lifted off the sands near Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. The First World War gave flying a large boost, but by the nineteen twenties it was still mostly a novelty, with few standards and self-taught daredevils barnstorming at county fairs, charging to take people for rides, and flying stunts such as wing walking, pulling banners, and making nuisances of themselves over cattle pastures.

Photo: Courtesy of the Paul Rinaldo Redfern Aviation Society of Columbia, South Carolina

Redfern's Stinson Detroiter on August 25, 1927.

Still, practical aspects of the aviation phenomenon had begun to make inroads. Aerial photography was a new, useful tool, as of course were wartime reconnaissance, airmail postal delivery, and fast—if not completely safe and dependable—transportation into and out of remote places. It was also a time of intense, and almost frantic, attempts at breaking records in the air, much like during the ages of sail, then steam. There were speed records, distance records, altitude records. One of the bleakest of these records is the list of dead record-seeking pilots, which numbered in the hundreds. Some pilots flew into clouds and then, delighted they did not get wet, got vertigo, spun out the bottom, and crashed and burned. They went so high that they stalled and simply hurtled back to earth. They flew into mountains in fog, or got torn apart in thunderstorms. They misnavigated and ran out of fuel, or out of daylight, or just out of time. For many of them, the longer they flew, the less time was on their side.

Boosters of all stripes dangled fat prizes in front of aviators in order to publicize everything from businesses to cities. Lindbergh had sought such a prize—$25,000 from a New York hotelier (roughly $300,000 in today’s money)—to fly nonstop from New York to Paris. So it was with Paul Redfern, at twenty-five (both he and Lindbergh were born the year before the Wright Brothers’ flight), when the Brunswick, Georgia, Board of Trade agreed to match the Lindbergh prize of $25,000 for the flier who could go nonstop to Rio. The board hoped the flight would put their tiny city on the map as an East Coast maritime hub on a par with Jacksonville or Savannah.

Perhaps it wasn’t such a fantastic notion—at least the publicity part. When Lindbergh arrived in Paris, he was mobbed by 150,000 people and became a world hero overnight. Back then, heroes had a lot more cachet than they do today.

By the time the Roaring Twenties came along, it seemed like everyplace in the country but the South was going gangbusters. New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles were making news and making money—even St. Louis, thanks in part to the name of Lindbergh’s plane, the Spirit of St. Louis. But down in poor old backward Dixie, nothing much was shaking. Sixty years after the Civil War had ended, the South seemed frozen in time. The Northern newspapers’ cartoons featured Southerners swatting flies, scratching their behinds, and spitting tobacco, or as buffoons sipping mint juleps on the veranda and speaking in comical drawls. There was a measure of truth in the stereotypes; the South had gone through rough times since the war and Reconstruction. In 1926 the University of Alabama had beaten the University of Washington in the Rose Bowl, but that was about the first thing of note the South could crow about since it won the Battle of Chancellorsville in 1863.

Yet there on the beach at Sea Island on that sultry August Thursday afternoon in 1927, Paul Redfern and his wife, Gertrude—whom he had met and married in Ohio two years earlier, while flying for her father—had assembled more than three thousand boosters and well-wishers, a gaggle of reporters, and a brand-new green-and-yellow (Brazil’s national colors) Stinson Detroiter monoplane christened Port of Brunswick that was ready to go to “Brazil or Bust.” Redfern intended to give them something to crow about now.

He’d “always had his head in the clouds,” family members said of Redfern, according to a local news story, which did not indicate whether this was intended as a compliment. What is known is that from a very early age he was a mechanical tinkerer infatuated with airplanes, often wore an aviator’s helmet, and at the age of sixteen actually constructed his own aircraft out of cardboard and spare parts that he billed as “the World’s Smallest Flying Machine” and that he flew around a cow pasture next to his school. Later he gave aerial rides to paying passengers at two dollars a hop, earned money doing acrobatic stunts at county fairs, became an “aerial advertising artist,” and even a Prohibition-era revenue agent, according to a story in the Columbia (S.C.) Star, by employing his aircraft in an unsportsmanlike manner to spot illegal whiskey stills. It was reported that he had been jailed in Texas for buzzing a train. Photographs of the flier show a rail-thin, intense-looking, wide-mouthed young man, often with a pair of goggles perched on his head. Exactly who thought up the idea of flying down to Rio is uncertain, but on the surface it seems like a harebrained scheme.

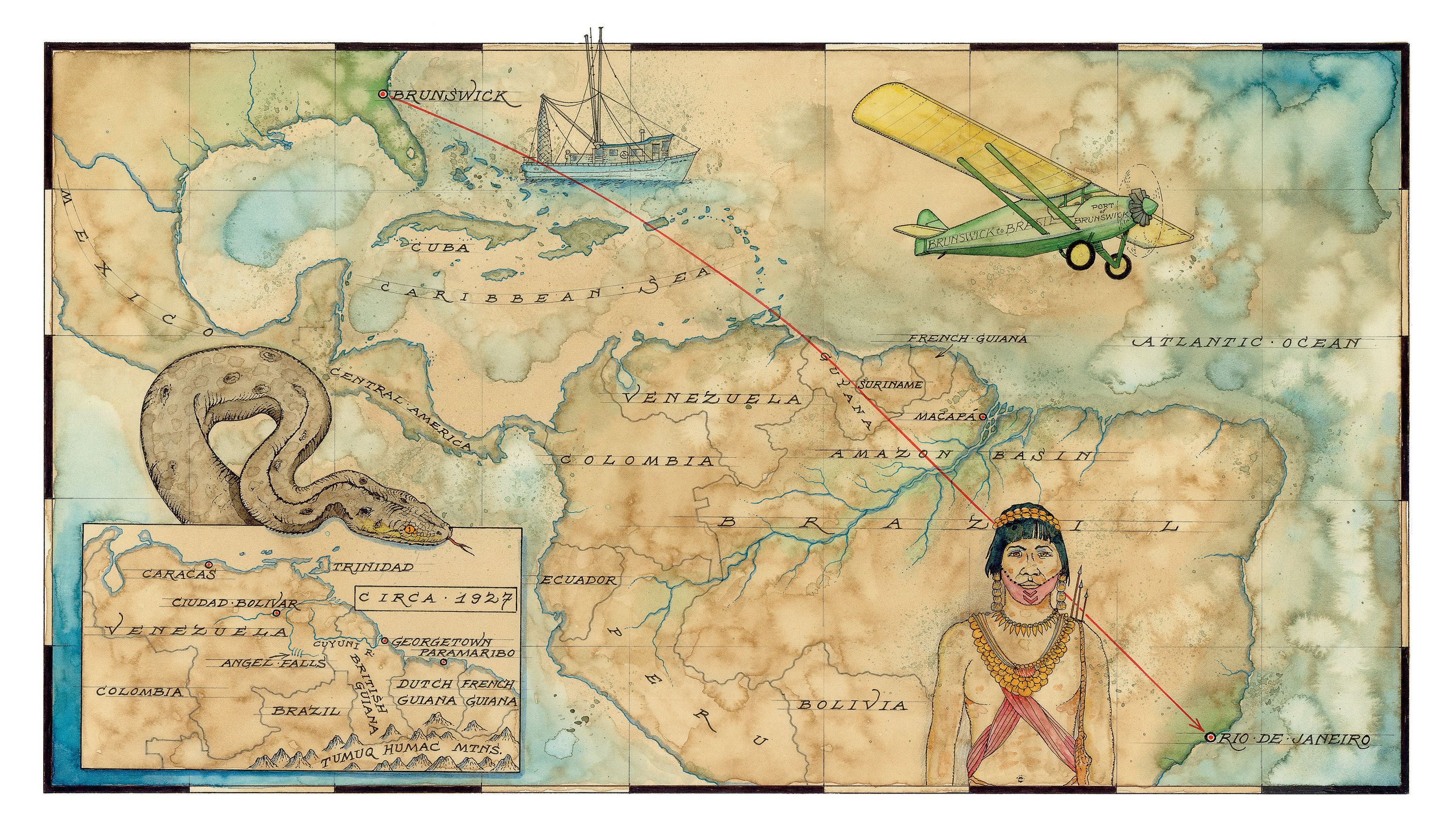

Illustration: Mike Reagan

First off, the distance alone should have been enough to intimidate any sensible person in 1927. It was 4,600 miles as the crow flies, half of it over empty ocean and half over the impenetrable jungles of the Amazon Basin, which were occupied by headhunters and cannibals, in case he had to put down.

Eddie Stinson himself, manufacturer of the brand-new $12,000 Stinson SM-1 Detroiter, warned Redfern it was “more than a man could stand” to try a solo flight of fifty-two hours, especially after Lindbergh reported falling asleep at the stick numerous times during his thirty-three-hour ordeal—but no dice. Rio it was. If the idea had been to fly solo nonstop to South America, Caracas would have done nicely, and was less than halfway to Rio, but the notion seems to have been not just breaking Lindbergh’s distance record, but busting it wide open.

The end of August was also the height of hurricane season, and in those days, with no satellites to forecast storms, Redfern could have flown right into one before he knew it. Moreover, he had picked a time of month that had no moon to fly through two ten-hour stretches of night. This was made worse by the fact that the barometric altimeter was still a year away from being invented, and the radio altimeter, which had been around for a couple of years, was not an option since Redfern had no radio. Putting it mildly, it was a seat-of-the-pants escapade. Since fuel was everything on a flight of that distance, the cockpit was terribly cramped. Spare fuel tanks were placed aft and also forward of the pilot’s seat, so the only way to see forward was through a small periscope in the fuselage, or out the side windows. Aside from fuel gauges, about all Redfern had was a compass, a map, and, one presumes, a couple of box lunches for the next two days of flying. Otherwise, he was in for hours of loud, droning boredom from daylight to dawn—twice over.

On the bright side, the New Zealand Evening Post reported that Redfern had packed a rifle, revolvers, ammunition, various knives and other weapons, fishhooks, flares, and baubles and beads “for trade with savage Indian tribes” he might encounter should he need to land prematurely. To reporters he declared: “Don’t lose hope if you don’t hear from me for two or three months. If I should be forced down in the Amazon Valley, I believe I can survive and will be able one day to walk out of that jungle”—bold words from a man who’d never been there before.

Redfern lifted into the sky and soared into the Atlantic over a startled Georgia shrimp fleet, then headed southeast at eighty-five miles per hour, and most likely at about five thousand feet of altitude, which would have been comfortable, especially that time of year. He somehow failed to crash and burn during the first cycle of nighttime hours, and emerged the next morning off Trinidad to notice far below him the wake of a ship that turned out to be the Norwegian tramp steamer Christian Krohg, upon which he descended and threw out a carton with a note asking for directions to South America. The ship indicated it was about two hundred miles due south, right where it was supposed to be, and that was the last anyone heard from Paul Redfern. However, an American engineer named Lee Dennison reported seeing the Port of Brunswick fly over Venezuela’s Ciudad Bolívar Plaza later that day, “trailing a thin wisp of black smoke.” He identified Redfern’s plane by its tail number.

On Redfern’s second night out, he was supposed to drop a flare over the Brazilian town of Macapá, near the mouth of the Amazon, which was in radio contact with Rio, where a festive display of banners, fireworks, papier-mâché, and other decorations were being assembled. Throngs of Brazilians were prepared to storm the airfield where Redfern expected to land, and carry him bodily—à la Lindbergh—into the city. Among those on hand were the president of Brazil and the silent-movie star Clara Bow, who had just appeared in the Oscar-winning aerial film Wings.

When the radio operator at Macapá reported to Rio that no one had seen a flare, a pall descended upon the city. The next day, faces scanned the skies until sunset, which was around the time that Redfern’s plane would have run out of gas. Then the mourning began.

No sophisticated techniques existed then to find a downed aircraft. If the sighting over Ciudad Bolívar was correct, Redfern’s plane would have gone down somewhere along a 2,500-mile route—about the distance from New York to L.A. The search area stretched from the triple-canopy wastes of the Amazon Basin to a region of rugged mountains inhabited by tribal peoples—in other words, locating him would be a practical impossibility—which naturally set into motion the most spectacular manhunt since Stanley found Livingstone.

More than a dozen rescue expeditions over the next decade kept Redfern alive in the American psyche. It usually went this way: A rumor of Redfern being stranded in the jungle would rise up, by native drums, or a stray Amazon Indian, or a Catholic missionary, or a bush pilot, prompting calls to organize and finance a rescue mission, which would then venture into the most dangerous and forbidding rain forest on earth.

The Amazon Basin is harsh enough today, but back then it must have been perfectly dreadful. There were all sorts of aboriginal tribes armed with spears, bows and arrows, poison-dart blowguns, and crude knives and axes, and many, if not most of them, were hostile. Some were notorious headhunters, and a few were cannibals.

The Redfern saga had its share of cranks and crackpots, as well as serious explorers and rescuers, on top of a few well-meaning fools and charlatans, all of whose involvement was breathlessly reported in the international press. In 1932 an account surfaced from an American engineer named Charles Hasler that Indians were holding captive in the jungle an American pilot whose legs had been broken, but it was not specific enough to provoke action.

In October 1935, William J. LaVarre, a Virginia-born, Harvard-educated diamond explorer, prompted an investigation of renewed Redfern rumors by the U.S. consulate in Dutch Guiana, which, according to Time magazine, “unearthed a Creole Catholic missionary named Melcherts” who [in December 1934] had dispatched a Bush Negro to the upper river [who] returned in February 1935 with the following story: “He was told of a white man who had come out of the sky, had both legs broken, and was living in an Indian village.”

As if in confirmation of this, two months later, on April 15, “an Indian…entered the hospital at Drie Tabbetjes suffering from yaws, and said he had seen [a white man] crippled, so that he could not walk, that he had come out of the sky, and had seen his machine, which was wrecked on a savanna and not a mountain.”

The U.S. State Department estimated it would take two or three months to reach this Indian village, and the explorer LaVarre organized a search party to take a crack at it. But after several weeks, he emerged from the jungle, admitting they had turned up nothing.

Next, Art Williams, a well-respected pilot living in British Guiana who said he had taught Redfern how to fly, reported that while performing an aerial survey in January 1936, he passed over an Indian village in Brazil, and while the Indians fled into the jungle he saw “a lone white man standing in the open and waving frantically to the plane.”

Williams claimed that he and a friend, Harry Wendt, set out in a small boat to find the village, which he had marked on his map, but when they arrived several days later, they were met by a tribe in war paint, heavily armed, and made a “narrow escape.”

Inspired by all the rumors, an expedition was launched in February 1936 by the Elbert S. Waid American Legion Post in the Panama Canal Zone, led by the post commander, W. L. Farrell, and James A. Ryan, a CBS correspondent. To cover costs, the expedition issued five thousand special “Redfern Rescue” stamp covers, postmarked from Dutch Guiana, which they hoped to sell to stamp collectors. (President Roosevelt, in fact, purchased two of them.) Three months later Farrell staggered out of the jungle to report finding no trace of Redfern, and that during the search his companion Ryan the CBS correspondent, had drowned.

That same month a Paramaribo newspaper published the account of one Alfred Harred, a freelance newspaper reporter who asserted that he and the former pilot Art Williams were navigating a floatplane on a boundary survey for British Guiana when they landed on a tributary of the Amazon. From there, Harred said, they “started to trek across the Tumuc-Humac Mountains” and soon “came upon a village where all Indians were completely nude. We saw an airplane caught in the branches of a big tree. A few hours later we met Redfern.

“He was dressed in a ragged singlet and underpants,” Harred continued, and “he looked like a man over forty, hobbling on rude crutches made of tree branches and liana. He found difficulty at first speaking English, but evidently he had been expecting to be found.” Williams gave him a biscuit and some tinned meat, Harred reported.

“He told us he had been forced down…. His legs and arms were broken in the crash, but medicine men cured him…. He had married an Indian woman and has a son who looks very much like him. When the Indians suspected we intended to take Paul away they threatened us with poisonous spears and arrows and on Paul’s advice we withdrew…with the intention of returning. It must be realized that any rescue must mean the use of force with probable death of Redfern.”

At last, some firsthand positive news, which quickly flashed around the world—until Art Williams was contacted at his home in Georgetown, British Guiana. He dismissed the entire account, stating, “I never saw Redfern or his plane,” and adding, “I do not recall meeting Harred.”

Photo: Courtesy of the Paul Rinaldo Redfern Aviation Society of Columbia, South Carolina

A search party led by Art Williams (second from left) on the border of Brazil and British Guiana in 1936.

Finally, in the waning months of 1937, New York sportsman and explorer Theodore J. Waldeck, at the behest of Redfern’s family, launched the thirteenth rescue expedition from British Guiana. His search party was soon marooned by high water on a desolate island called Devil’s Hole on the remote Cuyuni River, where one of the members, Dr. Frederick J. Fox, of New York, was seized with a jungle fever and died.

The others buried him there and continued on until April 27, 1938, when Waldeck reported to the world that he had discovered the wreckage of Redfern’s plane in Venezuela, and that he had proof positive the pilot was dead. Unfortunately, Waldeck declined to say what the proof was, and Redfern’s parents went to their graves still hoping their son was alive somewhere in the jungle.

Meantime, after ten years had passed, Gertrude Redfern had a Michigan judge declare her husband legally dead, and with that the matter was more or less closed.

Not a hank of hair or a piece of bone exists to prove Redfern’s fate, and yet there are still those who believe that he probably survived in the vast Amazon Basin—and that his offspring might live there yet. A street in Rio was named after him, as was an airfield on St. Simons Island in Georgia, which has since become the upscale Redfern Village of trendy shops and restaurants.

In the South Carolina state capital, Columbia, a group called the Paul Rinaldo Redfern Aviation Society gets together every August 25, and at precisely 12:46 p.m., the time that Port of Brunswick lifted off from the beach in 1927, they raise a toast to salute Redfern and his fabulous quest for fortune and fame. And why not?