Arts & Culture

The Wild, Thrilling, Southern Roots of the Most Expensive Gun Ever Sold

Photo: Adobe Images

In a year plagued by deep financial uncertainty across the world, the London auction house Bonhams bucked the trend by bringing a stunning Southern collection—arguably the world’s finest—of Early West firearms, documents, and memorabilia under the hammer. Jim and Theresa Earle of College Station, Texas, were the passionate, lifelong collectors. Jim, who died in 2019, was a beloved professor of engineering design at Texas A&M, work which arguably led to his affinity for beautifully crafted nineteenth-century American weaponry, but the hallmarks of the Earle collection were its rigorous narrative completeness and its impeccable provenance.

Included among the items (though rarely exhibited over the fifty years that the Earles built the collection, which they kept in the “gun room” of their home in Texas), were, for instance, W.B. “Bat” Masterson’s custom ordered nickel-plated 1885 Colt Single Action Army Revolver (with the accompanying letter from Colt, including the July 30, 1885, date of shipment); Wild Bill Hickok’s Springfield Trapdoor Rifle (that had been buried with him in 1876); and not least, the star lot of the sale, Pat Garrett’s Colt Single Action Army Revolver with which he killed Billy the Kid.

These and other lots were so fine that they immediately set the big money of the rarified world of arms collectors in motion. Bat Masterson’s Colt brought $375,312; Wild Bill’s Springfield very nearly rang in at a half-million dollars; and Pat Garrett’s deadly Colt—which he actually lifted off a friend of Billy’s, whom he arrested before he ambushed Billy with it on the night of July 14, 1881—lifted the sale into the stratosphere when the hammer fell at $6,030,312.

Photo: ANTHONY RATHBUN PHOTOGRAPHY/Courtesy of Bonhams

Pat Garrett's Colt revolver, used to kill Billy the Kid, sold for more than $6 million.

That price snappily doubled Bonhams’s high-end estimate of $3 million for the Garrett piece, and it made the vernacular, factory-made, late nineteenth-century six-shooter the most expensive firearm ever sold at auction in the world.

To put that in perspective—meaning, the financial value of the towering legend of Billy the Kid’s and his killer’s association with this firearm—the former most expensive firearms sold at auction in the world were a matched pair of bespoke French eighteenth-century saddle pistols that no less a historical character than the Marquis de Lafayette presented to none other than George Washington, who used them in the war and kept them for life. They sold at Christie’s in 2002 for $1,986,000.

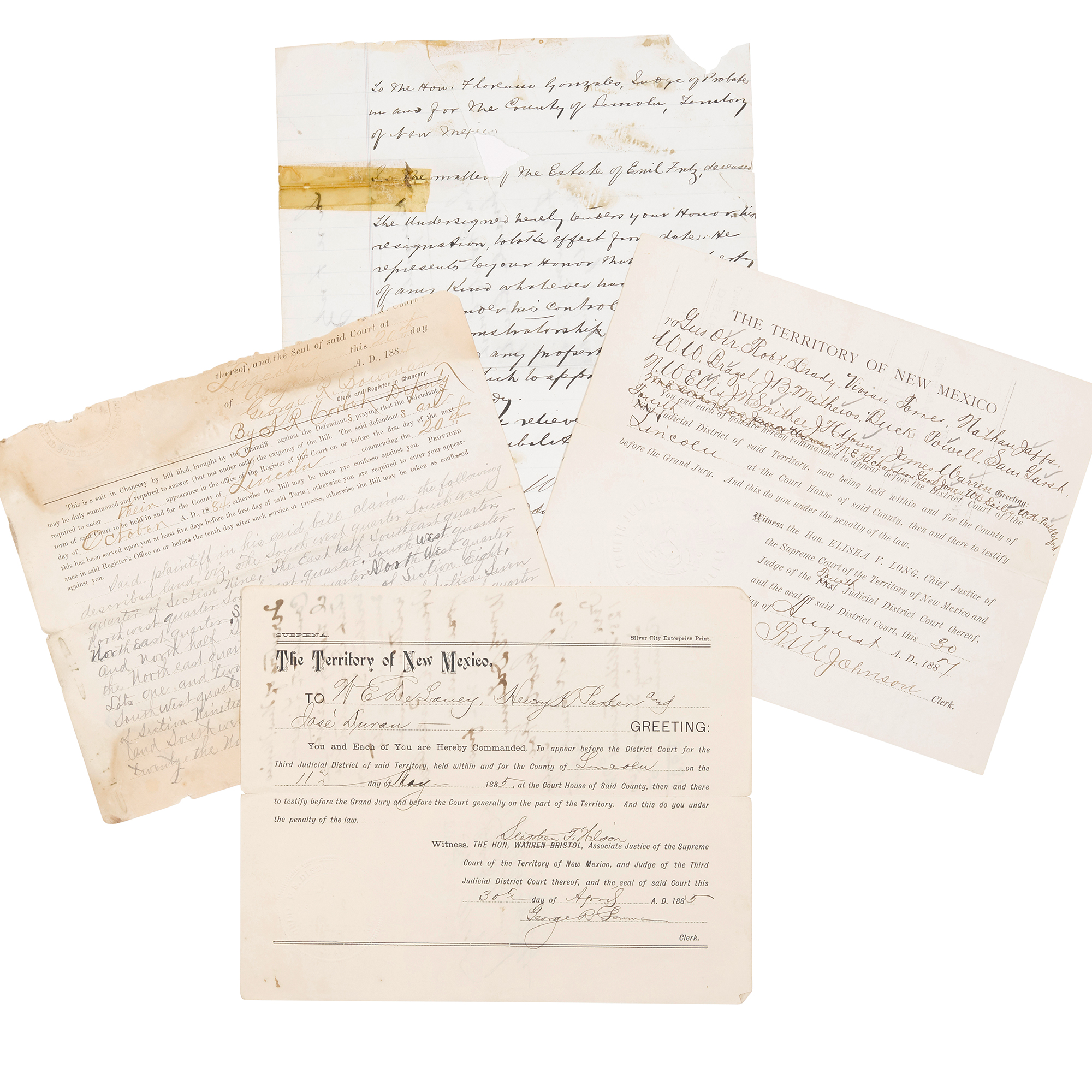

The Earles’ collection brought in a total of more than $12 million, and that stellar amount is due to their excellently tenacious, narrative collecting method. They identified central nineteenth-century events in the settlement of the West—such as the New Mexico territory’s 1878 “Lincoln County War,” which ultimately led to Pat Garrett’s midnight bushwhacking of Billy the Kid—and they set out to collect the most iconic objects and/or pieces of documentation around those events. In the Lincoln County War, the most iconic objects were the firearms belonging to the protagonists.

Put another way, the Earles didn’t stop when they got Pat Garrett’s revered Colt. Also in the Bonhams sale was Billy the Kid’s 10-gauge Whitney double-barreled Damascus steel shotgun that he stole during his famous jailbreak from Garrett’s deputy Bob Olinger, with which the Kid then killed Olinger. That shotgun came within a hair’s breadth of $1 million as the hammer fell. Which is to say, any gun that Billy killed with, or that killed Billy, went through the metaphorical roof.

Photo: Thann Clark/Courtesy of Bonhams

Billy the Kid’s Whitney double-barreled shotgun that he stole during his famous jailbreak was also in the sale.

The Earles didn’t stop there, either. They had Garrett’s elegant Smith & Wesson side piece from back when he was a buffalo hunter; Billy the Kid’s Winchester rifle (stolen by Billy from the Lincoln County jail armory during his escape); Pat Garrett’s gold Elgin pocket watch, bestowed on him by the grateful town of Lincoln; Deputy Bob Olinger’s silver pocket watch; and a signed arrest warrant from Garrett as sheriff of Lincoln County, New Mexico, where the cattle war in which he and Billy were caught up took place. The Kid’s beautifully burnished Winchester moved at $375,312.

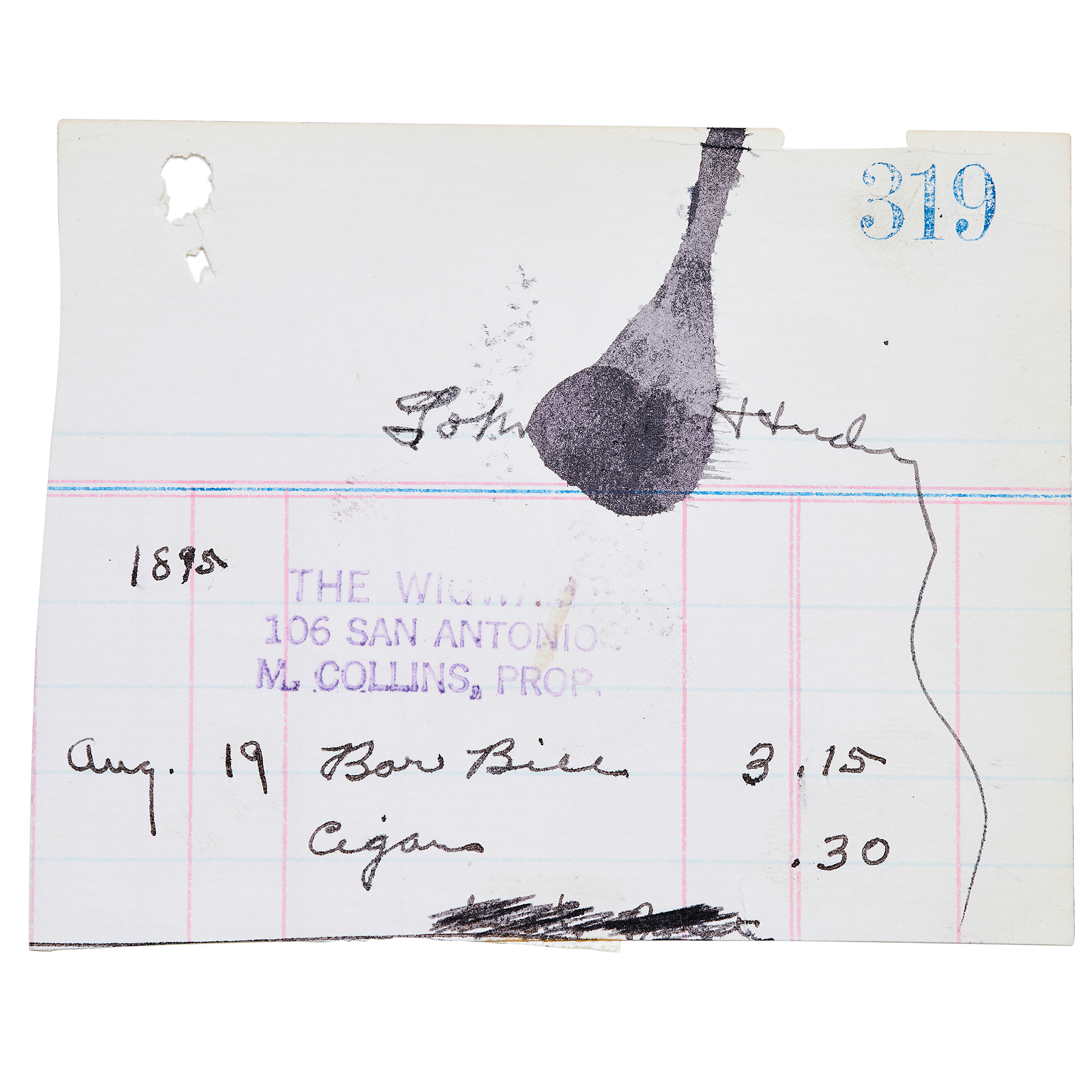

Similarly, the Earles tracked down both the Colt with which notorious outlaw John Wesley Hardin was shot in the back of the head while playing dice in the Acme Saloon in El Paso in August 1895—one of the more hotly contested firearms in the sale, raking in slightly more than $858,000—and Hardin’s own Smith & Wesson side piece that he carried but never got the chance to use on that August evening, which sold for more than $625,000.

Photo: ANTHONY RATHBUN PHOTOGRAPHY/Courtesy of Bonhams

John Wesley Hardin’s bar tab from the day he was shot in the back of the head at the Acme Saloon in El Paso.

The key to understanding the Earles’ collection is that, in the early settlement of the West, the outlaws and the lawmen were one and the same. It’s a diplomatic way of saying, the line between a hero and a villain out in the wild country of the American west was razor thin—any “heroes,” such as Wild Bill Hickok, were made later, as the shooting died down and the hyper-romanticized show-biz value of the Wild West took hold of the American imagination. Hickok famously capitalized on that show-biz transition, as did some of the other original actors—including the Alabama-born Garrett, who came from a family of penurious, failed planters and was ever in need of a buck, which is why Garrett and a journalist acquaintance tried to cash in on Billy’s killing by doing a book about him. The Earles dutifully added Garrett’s handwritten book contract to their collection.

The West’s distinct lack of heroes is perfectly demonstrated by the cyclone of violence swirling around Garrett and the Kid, whose guns and memorabilia accounted for two-thirds of the value of the entire Earle auction. The core reason for the larger conflict was that a corrupt pair of Lincoln businessmen, James Dolan and Lawrence Murphy, had cornered the mercantile and the cattle market of much of the territory—including having then-sheriff William Brady in their pocket. Billy worked as a ranch-hand for their main competitor, the British-born cattleman John Tunstall, whom Dolan and Murphy mercilessly had their enforcers murder. Blood revenge being the rule of the day, Billy joined the posse of “Regulators” who then avenged Tunstall’s death by killing Sheriff Brady. That, and Billy’s bloody jailbreak after his conviction for the crime, set the implacable Garrett on his trail, and thus the inevitable denouement of Garrett’s midnight ambush was set.

Photo: Thann Clark/Courtesy of Bonhams

Wild Bill Hickok’s Springfield Trapdoor Rifle, which had been buried with him in 1876, was among the items sold at auction.

They met improbably, in the middle of the night of July 14, 1881, at the Maxwell ranch, in Pete (Pedro) Maxwell’s bedroom. Garrett knew that Billy was friends with Maxwell, and there were rumors that Billy was reportedly courting Maxwell’s sister Paulita. As soon as he entered the darkened ranch-house bedroom, Billy sensed another presence besides Maxwell, and asked, in Spanish, “Quien es?” (“Who is it?”) Garrett shot twice with his Colt. There were no heroes in the room before, or after, those two shots. Garrett was in no mood to give the far younger twenty-one-year-old Billy, notoriously quick on the draw, a fair chance.

Jim and Theresa Earle understood all this. The Bonhams expert who shaped the extraordinary sale, Dr. Catherine Williamson, the house’s vice president and director of books and manuscripts in Los Angeles, is herself a native of Huntsville, Alabama, and grew up in Pensacola, Florida.

“I think what really distinguishes Jim Earle from other collectors was his patience,” Williamson says. “For instance, the Wild Bill Hickok rifle was buried with Hickok, and that took a long time to surface. Jim’s method was, he’d contact the owners or the descendants and ask if they were interested in selling whatever it was, and if they said no, he’d just put them on his Christmas card list every year and stay in touch. So, if they ever got interested in selling, there was Jim, who by that point wasn’t just ‘some collector,’ he was their friend. He didn’t do it just once.”

Down in the nether regions of the 265 lots, among the albumen prints of Geronimo with his sons and the portrait of Sitting Bull, were some surprising romantic literary finds—notably, that of the notorious James gang’s own Frank James, Jesse James’s brother and coleader. Cutting resolutely against the shoot-first-ask-questions-later myth that we groom of the James brothers, young Frank, in a burst of chivalric emotion, presented his beloved wife with the gift of a contemporary nineteenth-century account of King Arthur.

Photo: Courtesy of Bonhams

Documents from the New Mexico territory’s 1878 “Lincoln County War” were part of the Earles’ collection.

As a whole, what their grand collection proved was that Jim and Theresa Earle, a modest, extremely witty professor of engineering and his wife, down in a little college town in central Texas, were themselves among the world’s rarest collectors of anything—Old Masters, prehistoric art, arms and armor, you name it. They carried in their tool kit both an academic and an instinctive understanding of the cast of characters whose personal effects they targeted. Their collection brought $12 million because the Earles saw beyond the myth of the Old West. They saw the real actors of the day for what and whom they were. That collection, over a half-century in the South in its builders’ hands, is now strewn to the wind. Its like won’t be seen again.