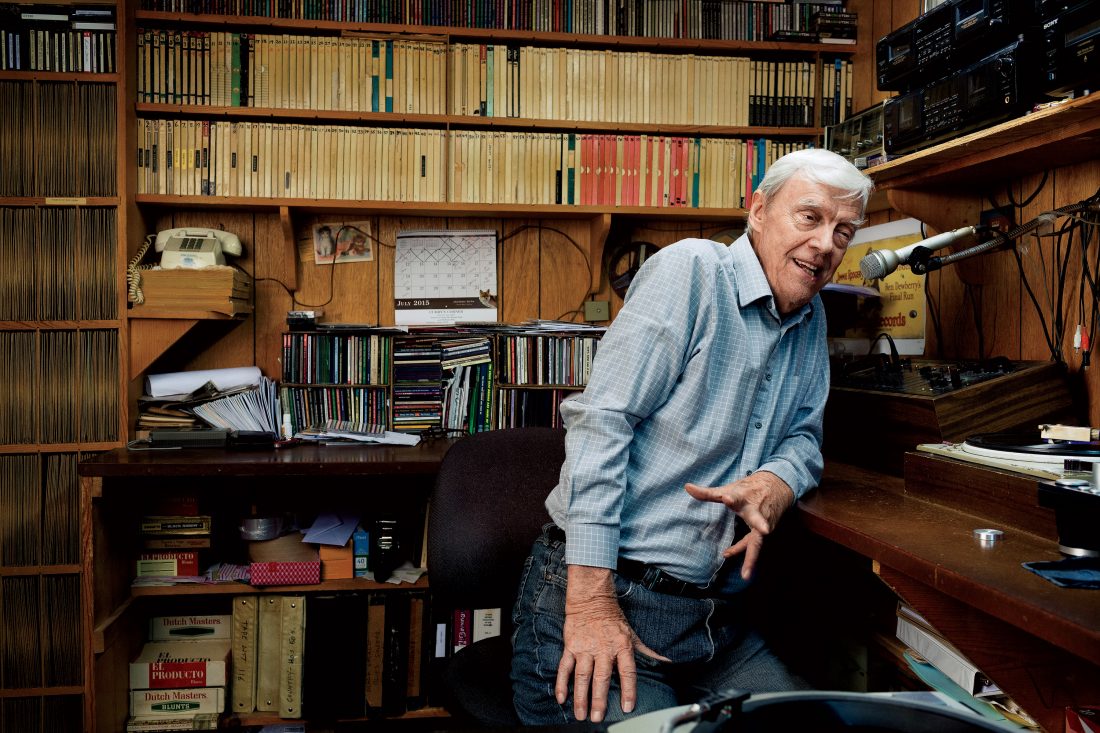

“I’m gonna start you off with my favorite singer,” says Joe Bussard as he swipes a 78-rpm record with a threadbare square of black velvet. We’re in the windowless basement of Bussard’s Maryland ranch house, and the lanky seventy-nine-year-old is perched on a cheap black office chair, swiveling like a pirate DJ between a shelf of vintage hi-fi equipment and a turntable resting on an old RCA Victor radio console. Bussard has wavy silver hair and bulgy eyes that nestle in pouches of dark flesh, as if he hasn’t slept since last Tuesday, which may be the case. The man has energy, especially when he’s spinning records.

Bussard drops the needle into the groove and flashes me a manic smile. A prelude of crackles and pops electrifies the stale air, and then the past explodes into Bussard’s basement—Jimmie Rodgers strumming his Martin guitar and singing, “I’m always blue, feeling so blue…” with that high, lonesome sound that Bob Dylan described as “the voice in the wilderness of your head.”

Photo: Eli Meir Kaplan

Bussard’s Edison cylinder phonograph.

Bussard grabs another Rodgers 78 from a bank of shelves. “You won’t believe who’s on this record,” he says, eyes bugging as he plays a 1930 recording of “Blue Yodel No. 9.” A trumpet erupts with the unbilled but unmistakable sound of Louis Armstrong.

“It’s like Satchmo’s right here in this room!” Bussard hollers, lifting an imaginary trumpet to his lips and losing himself in an air solo. “Ooh, you can’t beat them records!”

Joe Bussard is what my mother would call a bird. If he weren’t sitting here in front of me, toe-tapping and yodeling, I’d swear the man sprang from the imagination of the Dog of the South author Charles Portis, master of the oddball obsessive. Even the name is Portis-like. “It’s pronounced Boo-sard, but people say Buzz-erd,” Bussard explains, sounding at once deflated and matter-of-fact, before springing up to fetch a new record.

Unless you live under a rock, you’ve heard that vinyl is back. But the records Bussard collects predate vinyl. They’re 78s. Most were pressed from thick, brittle shellac mixed with clay. Introduced in the 1890s, 78s replaced phonograph cylinders, the earliest commercial medium for recording and playing back sounds. The discs are typically ten inches wide and contain one song per side, about three minutes; less common twelve-inch 78s have room for five minutes per side. The medium dominated recorded music until the 1950s, when 45s and LPs—pressed from thinner, more pliable polyvinyl chloride and spun at 45 and 33 ¹∕³ rpm, respectively—made 78s obsolete.

Bussard owns more than fifteen thousand 78s. He doesn’t collect them because they’re old or valuable, although they are. His obsession began when he was still a young boy and for one simple reason.

“The music,” he says. “Powerful music. The best music in the world.”

Specifically, he means blues, country, gospel, and jazz from the late 1920s and early 1930s—a sweet spot in American music history that would have been forgotten had it not been captured in the grooves of these discs. Bussard’s collection is heavy on the South. He owns rare Carter Family singles and a copy of everything Jimmie Rodgers recorded in his short life, a total of 109 songs. And he has vast numbers of “race records,” 78s by black musicians for black listeners, on labels such as Black Swan, Paramount, and Black Patti Records.

Photo: Eli Meir Kaplan

From the Archives

A rare “race record,” “Original Stack O’Lee Blues,” released by the Black Patti label.

Bussard’s awakening began around age six, when he heard Gene Autry’s voice issuing from his father’s old windup Victrola. Then he heard Jimmie Rodgers, and the music penetrated his soul. None of the stores in Frederick, where Bussard has lived all his life, carried Rodgers. The only child of parents in the farm-equipment business, Bussard asked strangers on front porches if they had any old records he could have or buy. They did. In 1949, when Bussard was thirteen, he rigged up a crude transmitter in his parents’ basement and began broadcasting hillbilly music over a pirated radio frequency. In 1955, after a local station complained, the FCC finally shut him down. That same year, Chuck Berry released his first single, “Maybellene,” the first Elvis Presley concert riot broke out, and Bussard landed a gig playing hillbilly oldies at WSIG in Mount Jackson, Virginia. From day one, he hated rock and roll.

“Watered-down bullshit,” he calls it. “Talentless people making millions yelling and screaming, jumping up and down like kids in kindergarten.”

Since 1955, Bussard has continuously produced Country Classics, a weekly hour-long radio show. It airs on WREK in Atlanta and a few other stations around the South. He records the show on cassette tapes in his basement and mails them out.

A high-school dropout, Bussard ran his own record label, Fonotone, from 1956 to 1969. The last company in America to produce 78s, Fonotone wasn’t a big moneymaker. Bussard’s most notable artist was the influential but obscure roots guitarist John Fahey. During this period, while mining for old 78s in Johnson City, Tennessee, Bussard struck his first rich vein. A Chevrolet dealer had bought a record store’s inventory and was selling it out of his parts warehouse for ten cents apiece. Bussard drove away with more than 3,500 records stuffed into his Ford Galaxie, which sagged so low he had to put extra air in the tires. “I was creeping up I-81 at fifty miles per hour, smiling all the way,” he says.

Another time, in a holler near War, West Virginia, Bussard gave an old-timer a lift.

“You got any old records?” Bussard asked.

The man did. A box full of mint-condition 78s stored under the bed, including fifteen records released by Black Patti, which has been called the “rarest American record label ever.”

“How much you want?” Bussard asked.

“Give me ten dollars.”

One of the lot, the Down Home Boys’ 1927 recording of “Original Stack O’ Lee Blues,” is the only copy known to exist. It’s worth upwards of $50,000 today.

Bussard’s collection might be valuable, but the collector’s knowledge base is priceless. As we listen, he hits me with an avalanche of dates and details about original recording techniques. He plays one of the last songs Jimmie Rodgers recorded, bedridden and dying from tuberculosis, and points out where his voice falters on the word home. The pathos gives me chills. He plays the Dixon Brothers’ “Sales Tax on the Women” on the Bluebird label, recorded in a Charlotte hotel, describing the makeshift studio and turning up the volume so I can hear the barking of a lapdog belonging to one of the hotel’s guests.

“He’s doing important work,” says Lance Ledbetter, founder of the Atlanta-based record and reissue label and publishing company Dust-to-Digital. “Places like the Library of Congress have a staff of archivists, conservationists, librarians. Joe Bussard embodies that entire workforce.” Doc Watson stopped by to visit Bussard back in the 1980s. The vinyl evangelist Jack White recently came to marvel at Bussard’s man cave.

“With Joe, it’s like walking into another world,” says Ledbetter, who reached out to the collector fifteen years ago while spinning records at Georgia State University’s radio station. Since then, the pair have collaborated on several reissues. Their upcoming CD, The Year of Jubilo, is a Civil War tribute featuring 78s gleaned from Bussard’s collection. “You’re in that space, transported back in time,” Ledbetter explains. “Joe’s at the controls, getting more and more amped up.” Bussard’s energy is infectious. For a fellow crate digger like Ledbetter, “it’s almost heaven.”