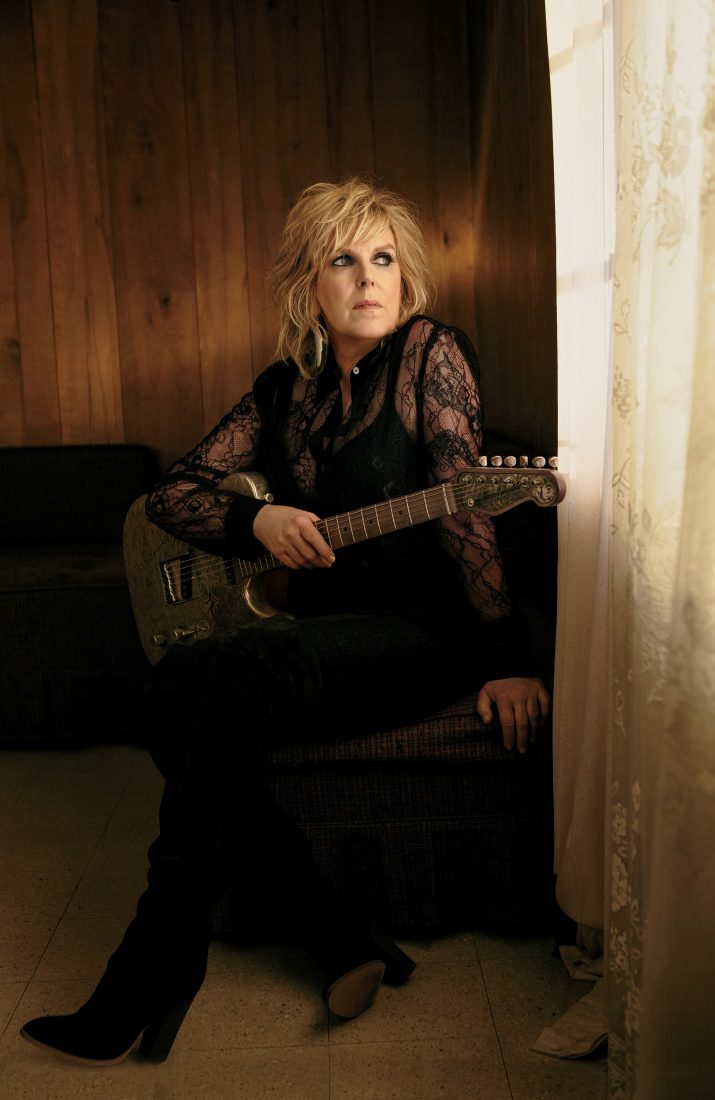

Lucinda Williams is singing. This isn’t unusual, of course. But the venue is a bit out of left field. Wearing a black sweatshirt, black jeans, and old-school Converse sneakers, the alt-country icon is sitting at a table in the lobby bar of Nashville’s Loews Vanderbilt Hotel. The night before at the Ryman Auditorium, Williams took home Album of the Year at the Americana Honors & Awards for her 2014 effort, Down Where the Spirit Meets the Bone. It’s now late afternoon, and she’s a little giddy. After a sip of red wine, she clears her throat, and in that trademark gravelly drawl—a voice that Emmylou Harris famously noted could take “the chrome off a trailer hitch”—begins to sing. “There’s a place in my heart I got room to spare, there’s a place in my heart I made room for you there, even though you make me blue, I got room for you…”

It’s a song from her upcoming The Ghosts of Highway 20 (out in January), an album that has the feel of a masterpiece, perhaps rivaled only by her 1998 breakout, Car Wheels on a Gravel Road. And despite the din of a corporate schmooze fest on the other side of the room and the house stereo system cranking, Williams’s voice still pierces the thick, boozy air. A bartender looks up and smiles; a waitress comes over and gives her a big hug. “We stay here whenever we come to Nashville,” Williams says with a smile. “They’ve gotten to know me.”

Over the course of more than thirty years, eleven albums, three Grammy Awards, and countless accolades and nominations, everyone has had the opportunity to get to know Williams, who is now sixty-two. Born in Lake Charles, Louisiana, she has unflinchingly chronicled the dark corners of her life, from being raised all over the South in a family eventually ripped apart by her mother’s mental illness to her own struggles with depression and volatility to disastrous relationships, including one in which she suffered physical abuse. Williams easily moves between blues, country, and folk, and with each verse or turn of phrase, she can wring the angst and darkness out of her soul until it’s nothing but dust. And then somehow pick herself back up and find a little more to squeeze dry. It’s a struggle to come up with the name of a more confessional and affecting songwriter working today.

“Believe it or not, I am a glass-half-full person,” she says, putting on her reading glasses to look at the menu. “If I allowed myself to get swallowed up in all this misery and vengeance, God knows what would happen. I mean, there aren’t too many choices. You can either hang in there or not.” Williams’s marriage to her manager, Tom Overby, in 2009—they got hitched onstage during her show in Minneapolis—has given her a brick wall on which to lean. He guides her with a gentle hand, part sounding board and part crate digger who finds her old demos on cassette tapes and might nudge her to take another crack at a certain song or idea, some of which found their way onto The Ghosts of Highway 20.

The concept for the album, which stands as something like a road trip through her life, got a jump start several years ago after Williams played a show in Macon, Georgia, where she had lived during part of her elementary school years. Outside she struck up a conversation with an elderly woman. “She started telling me her story, and I was just overwhelmed with the feeling of how long ago I had lived there and all the memories,” Williams recalls. After the show, her tour bus headed to Atlanta and then due west on Interstate 20. Watching out the window, she saw the exits tick by, triggering a flood of memories of places where Williams had a connection. “We lived in Atlanta for a year,” she continues. “We lived in Macon for a couple of years. My brother was born in Vicksburg, Mississippi. My sister was born in Jackson. My mother was buried in Monroe, Louisiana. So it kind of all came full circle.”

Beyond the way it feels, where Ghosts really shines is in the way it sounds. Her barbed-wire grit is soothed by jazzier arrangements, woozy atmospherics, and a nearly fourteen-minute-long reggae-inflected version of Mississippi Fred McDowell’s “Just a Little More Faith.” The preeminent jazz guitarist Bill Frisell joined Williams in the studio, giving many songs a haunting cloak that Williams wraps around herself as she plumbs emotional depths that would positively cripple regular folks.

The song she sings in the Loews bar, “Place in My Heart,” was partly inspired by her brother. He lives a short distance from Williams in Los Angeles now, though she says she never sees him. “After my mother died in 2004, he just kind of checked out,” she says. “I’ve got a number and his e-mail address and I’ve reached out. He just can’t…or doesn’t want to, I don’t know.” Williams remained close to her father, the acclaimed poet Miller Williams, until he passed away last January from Alzheimer’s complications. “If My Love Could Kill” chronicles the creeping, ruthless decline of a man so loved for his way with words. “A couple of years ago, he told me he couldn’t write poetry anymore,” she says. “That was worse than the day he actually passed away.” She reaches for a napkin to dab her eyes. Given the unrelenting rawness of Williams’s songs, it’s somewhat unnerving to actually see her cry. Suffice it to say, more napkins are needed at the table, and not just for her. “My dad used to say, ‘Honey, there’s a big deep, dark well and we’re all standing around the edge and some of us fall in and some of us don’t,’” she says. “That’s the difference. It’s pretty simple.”

An hour and a half later, after a quick change of clothes in her room, Williams—now wearing all leather: black vest, burgundy pants—and Overby grab an Uber car to the Stone Fox, a club in the Nations, a hardscrabble neighborhood west of downtown Nashville. In the car, the two talk about moving back to Nashville, a city Williams called home for a time in the 1990s. “When I lived here you couldn’t get a decent glass of wine,” she says. “Now, all our friends are here, no one’s left in L.A.” The car pulls up and Overby leads her into the packed club. Williams’s white-hot touring band, Buick 6, is onstage, and word has leaked out that Williams will join them for a few songs. “Gosh, I didn’t want this to be a big deal,” she whispers.

But as Buick 6 winds down with some fierce Texas boogie, Williams walks to the stage with her glass of wine—as she dubs it, her “milk of magnesia”—and begins delivering a rock-and-roll sermon, scatting across the tiny stage, bobbing her head up, down, and around the mic as if she were in the ring with Muhammad Ali. “People ask me, ‘What’s your idea of God? What are your thoughts on that?’” she shouts as the Buick 6 guys push a cover of Gregg Allman’s “It’s Not My Cross to Bear” to a swirling blues-stomp peak. She raises her arms overhead. “Well, it’s how I feel right now. I’m so blessed. Thank you so much. I’m so happy right now.”