John T. Edge has been scouring backroads and smokehouses for the stories behind Southern food since long before cast iron and country ham caught on with the rest of the country. A native of Clinton, Georgia, Edge left a corporate job in Atlanta for the graduate program in Southern Studies at the University of Mississippi before co-founding the Southern Foodways Alliance there in 1999. He has since become a go-to authority for publications including the New York Times and Gourmet, and has been a Garden & Gun contributor since its first year in 2007. His books include 2002’s Southern Belly and 2004’s Fried Chicken: An American Story, and as director of the Southern Foodways Alliance, he has showcased and encouraged some of the region’s brightest lights—people like chef Sean Brock and pit master Rodney Scott. But in Edge’s new book, The Potlikker Papers, he tells an even bigger story.

Photo: Jason Thrasher

Author John T. Edge.

A food history of the South from 1955 to 2015, the book opens with an African-American cook watching Martin Luther King, Jr. speak at the Holy Street Baptist Church and closes with a meal featuring frozen mint juleps and country ham tamales from Bill Smith of Crook’s Corner in Chapel Hill and his Mexican kitchen staff. In between, Edge unravels decades of regional food culture populated by a diverse cast of characters, from civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer and KFC founder Harland Sanders to larger-than-life celebrity chef Paul Prudhomme and home-cooking hero Nathalie Dupree.

The book comes out on May 16 and is available for pre-order. We spoke with Edge for more of his thoughts on the book, the Southern food boom, and why the South has more to offer than ever.

You’ve been writing about the South and Southern food for nearly two decades. Why write this book now?

About ten years ago, I began to try to write a history of the South, told through food, from the Civil War to the present day. Along the way, I realized that if you start post–Civil War, then you’re reacting to the Civil War—and I realized that’s not the moment in our history when I want to begin the story. I decided to frame the book based on the time when the South really began to change—in 1955, continuing on to 2015. That gave me a sixty-year frame, which was a nice, neat bundle for the narrative. After that moment, I had a kind of catalytic force that drove the book forward.

Photo: Copyright James H. Peppler, reproduced with permission of the photographer

Georgia Gilmore fueled the 1955-56 bus boycotts and fed the civil rights movement from her Montgomery, Alabama, kitchen.

How do you explain the rest of the country’s ravenous appetite for Southern food in recent years?

I think it’s part of a cyclical rediscovery of the South that seems to happen every decade or so. The 1960s so-called discovery of soul food was the discovery and celebration of rural Southerners gone to the North and the urban South. Craig Claiborne, a son of Mississippi, traveled while he was the New York Times food editor to Rooster’s in Harlem for chitlins and champagne. In the 1980s, it was Paul Prudhomme. Then and now, the South is the place where Americans come looking for regional cuisine. I think it is a little different this time, though. As the South evolves and progresses, fitfully, we’re putting distance between today and the lunges of Bull Connor’s police dogs in Birmingham in the 1960s. As that distance widens, Southern cultural products in general are in a renaissance. We’re seeing a wider American respect for Southern products—not just in food but in music and fashion. Look at the Alabama Shakes, Natalie Chanin, Billy Reid… We’re moving beyond Southern theme restaurants in New York City and San Francisco and seeing, instead, a mainstreaming of Southern food as America’s regional food.

Do you see a backlash coming?

The South is always going to get a little backlash. If we get a little too self-proud, if we… Well, this is something [Southern Foodways Alliance founding director] John Egerton said often. We, as Southerners, can be profoundly proud of what we’ve wrought amidst adversity, but we always have to keep in mind the trials, tribulations, and horrors of our history.

Why is the South still, after years in the spotlight, the country’s hottest food region—as opposed to, say, New England or the Pacific Northwest?

Our region is comparable in size to Western Europe, and yet, if you’re at Hog and Hominy in Memphis, you’ll see menu shout-outs to Ryan Prewitt of Peche in New Orleans and Mike Lata of the Ordinary in Charleston. You’ve spanned the entire region on that one menu. To [chefs] Andy Ticer and Mike Hudman, that’s the definition of “local” and “community.” Without being too chest bump-y, that’s what’s different. There’s certainly rancor among folks in our community, but the abiding spirit is one of collaboration and respect. I think that menu gives you a great idea of the interconnectedness of the South—the tethers that will hold our culinary community together when we’re no longer the splashy thing on the front cover of Bon Appetit.

You write in your book about the changing definitions of Southern food and culture as immigrants arrive from Mexico, India, and other parts of the world. Southern food has always been a melting pot, but how will we continue to define what’s Southern as it transforms? If a Mexican immigrant is making a tamale in Atlanta, is it Southern?

I think the definition of Southern food is commodious enough to welcome a Mexican immigrant tamale maker, and our history is complex enough that we can say, well, this tamale that I just ordered at a Oaxacan-owned restaurant just off Buford Highway in Atlanta does have historical roots here. Corn was borrowed from Mexico and Central America. Tamales have been part of cotton-growing culture here since at least the early years of the twentieth century. Take a look at Taqueria del Sol, where chef Eddie Hernandez has forged a kind of twenty-first-century meat-and-three that honestly fuses Monterrey, Mexico, and Memphis, Tennessee. It’s turnip greens with chiles, and fried chicken tacos. This is not fusion food. It’s an honest marriage born of cultural mixing.

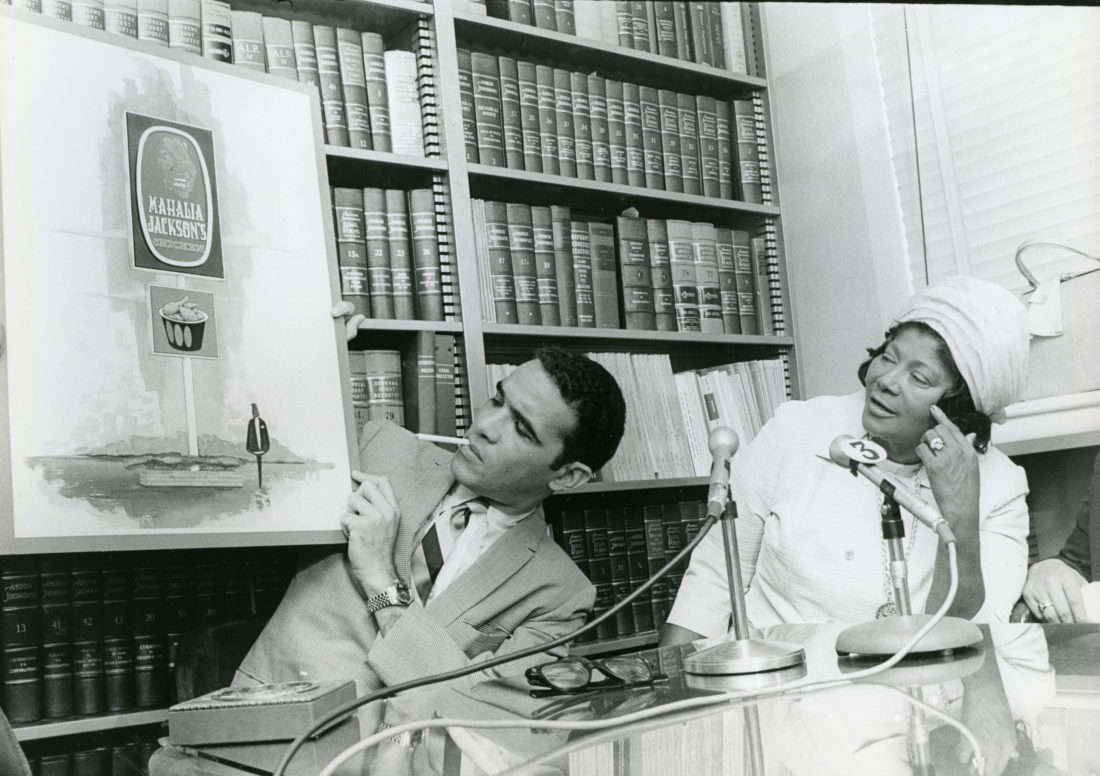

Photo: Photographer Vernon Matthews, reprinted with permission of the Preservation and Special Collections Department, University Libraries, University of Memphis

In the 1970s, black Southerners on a path to economic independence developed fast-food businesses. Here, Russell Sugarmon and Mahalia Jackson review plans for the Memphis opening of Mahalia Jackson’s Fried Chicken.

As the South grows and changes, do you worry at all for the future of more traditional dishes like skillet-fried chicken and whole hog barbecue?

I think there’s a false premise here. Culture is a process, not a product. Barbecue has evolved for the past three hundred years, and it will evolve over the next. Our cultural forms will mutate and take other forms and perhaps, in the long run, return to the original. But the ways in which cultures borrow and assimilate keep me interested. If the South were full of repertory restaurants that only cooked that one dish and got that one dish right… Well, that would be no fun. That would be boring. I love the Andy Griffith Show, but the fifth time I see a repeat, I’m like, “Okay, I’m good for now.”

If you were to add another chapter to the book covering the past year, what would you address?

This is a tough moment no matter what side of the political divide you’re on. It’s a moment of unease, distrust, and fear. Going forward for me, I’ve become really interested in the ideals and history and kind of lived practice of hospitality in this moment that seems very inhospitable. Here we stand in this, by reputation, most hospitable of regions. What does this moment offer a Southerner? These questions are national, but I think a Southern perspective on them can offer new insights for the whole of the country. That’s where I’m digging in.