When Hurricane Florence loomed toward the Carolinas this September, I packed a bag to leave. Along with clothes and a book, I tucked one item into the hidden pocket of my purse. We didn’t know yet where the storm would make landfall, but just in case something happened to Charleston, where Garden & Gun is based, I wanted to know my great-grandmother’s ring was with me. Before she died at age 95, alone on her Southern Missouri farm, Opal dropped her opal wedding ring into my palm. “I don’t remember which husband gave this to me,” she said. She outlived three. The tiny stone had fallen out twice in her garden, but each time, she found it while digging around her cucumbers, and would reset the jewel. The humble hand-bent golden prongs remind me of her—stubborn, resilient, shaped by time and hands in the soil.

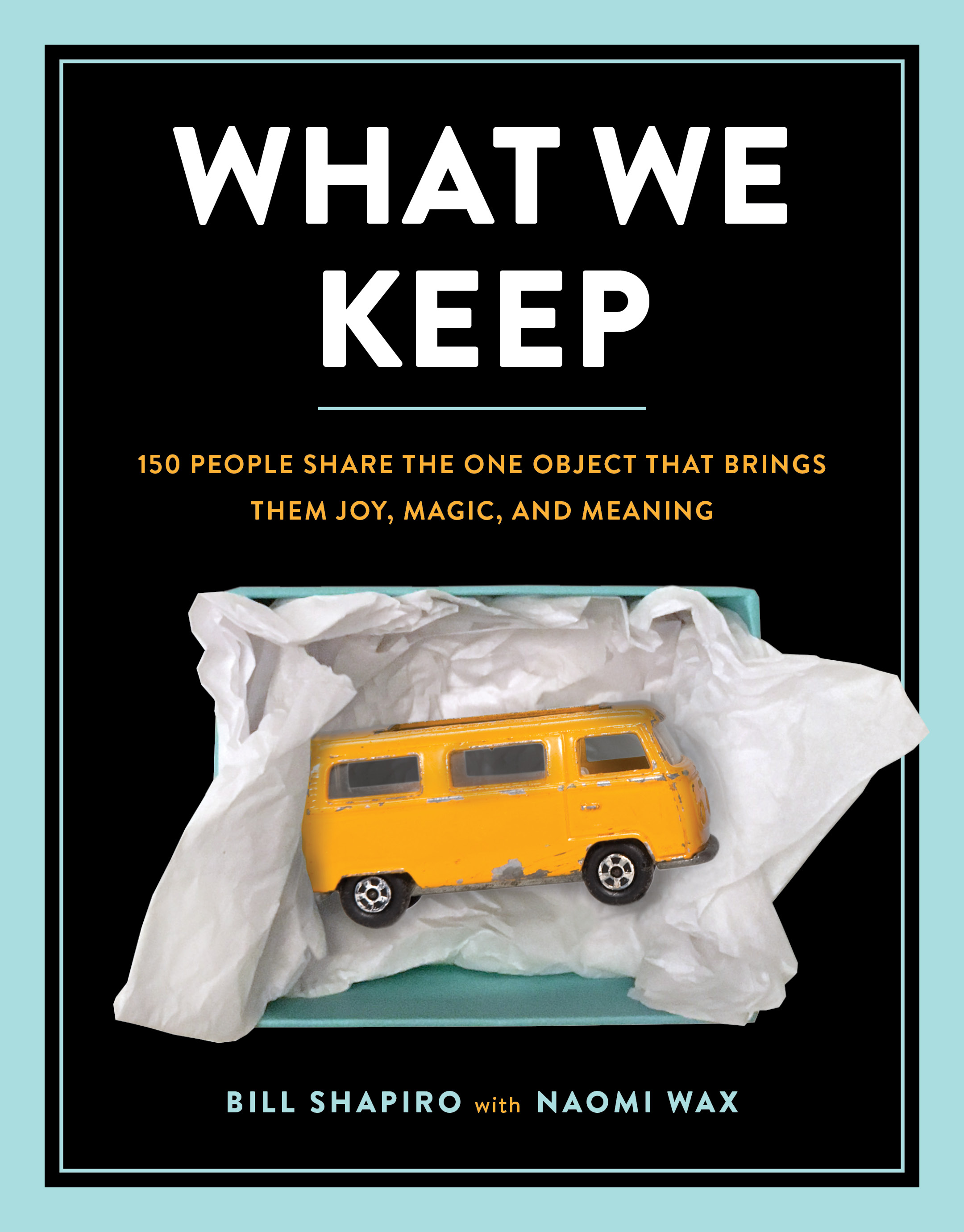

It’s just these sort of sentimental stories that the writers Bill Shapiro and Naomi Wax were after when they traveled the country for their new book, What We Keep: 150 People Share The One Object That Brings Them Joy, Magic, And Meaning. Shapiro, who is a former editor of Life magazine, was inspired by a locket he picked up at a junk sale. “It had a beautiful inscription, and I wondered how something that special could end up in a box of stuff for sale to strangers,” he says. “It got us thinking about the stories behind objects, and what is important to people.”

Shapiro and Wax interviewed folks from across all occupations and places—a truck driver in Texas; a game warden in South Carolina; the head of the Library of Congress. “We learned what matters most to people,” Shapiro says. “They saved this thing for a reason, maybe because someone who they loved gave it to them, or maybe because they came across it at a point in their lives when it meant freedom or possibility to them.”

We understand these sentiments in the South, land of heirlooms, engraved silver, and hand-me-down recipes. And more so than ever, land forever changed by storms. Here are seven stories from the book about what Southerners hold dear.

Justin Conway

The jewelry designer’s shark tooth

Cumberland Island, Georgia

Gogo Ferguson’s family has lived on Cumberland Island for seven generations. A jewelry designer, Ferguson often walks the tide line in search of treasures to turn into wearable art. “I’ve found a 25-pound woolly mammoth molar, alligator skulls, a camel’s tooth, rattlesnake ribs, thousands of things, but when I found this petrified shark’s tooth, I could not put it down,” she says. “The tooth is millions of years old, and it was millions of years old before the Timucua Indians, who once occupied the island, made it into an arrowhead. Think of all the hands that have touched this object. And one day it will pass through my hands and into my daughter’s.”

The game warden’s cast iron skillet

Charleston, South Carolina

Photo Courtesy Running Press

“My grandmother had a great hand in my upbringing, an original steel magnolia, presiding over the dinner table and running a tight ship,” says Benjamin McCutchen Moise, a retired game warden who lives in Charleston, South Carolina. He remembers traveling to the midlands of the state to visit his grandmother as a boy. “From the upstairs, where I slept, you could smell coffee and bacon and maybe liver pudding wafting up the stairs. I know she had it for close to 50 years, and I’ve had it for 50 years after that. I never put the skillet in the cabinet, and it was equally a fixture on top of her stove.”

The professional driver’s license

Austin, Texas

photo Courtesy Running Press

Killer Bramer has been a truck and bus driver for twenty-two years. The item that makes her most proud is her commercial driver’s license, which she earned at age 21. “I took the test in Lumberton, North Carolina, on a chicken farm, and I was the only girl in the class,” she says. “It’s just the hardest thing I’ve ever done in my life. Imagine backing up in an 80-foot-long vehicle that weighs 80,000 pounds. But I practiced and practiced in all kinds of situations, and I graduated number one.” The road she’s traveled has taken her to fascinating places—she transported the traveling Evel Knievel museum and served as Arlo Guthrie’s tour manager and bus driver. “The people I’ve met, the things I’ve seen—my life has been so odd, and I’m having such a ball,” she says.

The nursery owner’s family gourds

Sterrett, Alabama

Mary Beth Shaddix

David Shaddix runs Maple Valley Nursery in a small Alabama town, where he grows gourds that he turns into dozens of homes for purple martins, just like his grandpa did. “My grandfather lived in a tiny town called Saks, near Anniston, Alabama,” Shaddix says. “He worked a blue-collar job in a textile mill and wore overalls. I’d visit in the summers and watch him in the garden. He planted birdhouse gourds that he’d turn into homes for purple martins, which he loved. Some years after he passed, I brought my wife to see his homeplace, which my uncle looks after now. We got to talking about seeds and my uncle mentioned that Pawpaw’s seeds were still in the freezer. We opened it and there they were: white, threadbare pillow sacks with Pawpaw’s writing on them. I planted them the following season. I don’t know how to put it into words, but when I’m in the garden, I feel the connection to my grandfather, like we’re working together.”

The Librarian of Congress’s ceramic cup

Washington, D.C.

Photo Courtesy Running Press

Carla Hayden is in charge of 164 million items in her position as head librarian at the Library of Congress. This special cup was a gift from her mother, who painted it during an after-school youth program she was helping with in New York in the 1950s. “When you’re a kid—and I was six or seven at the time—you get a little jealous when your parent is doing stuff with other children, so this was important to me,” Hayden says. “But there was something else… the cup looked like me—it was one of the earliest things I had with a brown face. It’s been on my dressing table for years.”

The outdoorsman’s paddle

Chevy Chase, Maryland

Carter Roberts is the CEO and president of the World Wildlife Fund, and was moved by the story a fisherman in Mozambique told him when he handed him his boat paddle. “It’s not the most elegant paddle I’ve seen, but every part of it tells a story. On one side of the blade, there’s an etched set of lines. Like a checkerboard,” Roberts says. “[The fisherman] told me that during the years when the fisheries were cleaned out, the fishermen would pass the time by playing a board game on the blade. I keep the paddle by my desk. It reminds me of what’s at stake if we don’t care for the land and the ocean.”

Darren S. Higgins

The artist’s tintype images

Atlanta, Georgia

The mixed-media artist Radcliffe Bailey’s sculptures and paintings are included in the collections of the Smithsonian and Metropolitan Museum of Art. When he was just a young man in art school and unsure of what sort of creative mark he would leave on the world, he stayed with his grandmother in Palmyra, Virginia. “At one point, she went to the back of the house and came out with the family photo album,” he says. “It was thick and old and full of tintypes, probably from the late 1800s. She gave it to me. It wasn’t long before I started using the photographs in my work. These kinds of pictures usually end up in antique shops or are discarded or lost, so having them in a museum or gallery was my way of giving them a longer life than they would have had, of saving my family history.”

Photo Courtesy Running Press

Quotes excerpted with permission from What We Keep, copyright 2018 by Bill Shapiro and Naomi Wax, Running Press.