The Fourth of July 1988 was particularly balmy in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, or at least it felt that way as the daytime drinks took effect. I was at a farmhouse party in the middle of a cornfield, enjoying a day off from my job in the kitchen at Crook’s Corner. Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass weaved their way through Whipped Cream & Other Delights while I reclined into a particularly comfortable beige Goodwill love seat with a barbecue rib in one hand and a Yellowbird, an orange juice–vodka thing that might as well have been Orange Crush for as easily as it went down, in the other.

Just as I had submitted to the cadence of horseshoes clanging across the yard, a rustle among the cornstalks snapped me back to reality. Slowly, a giant Great Dane emerged, rolling an enormous rock with its nose, through the rows and over the yard, where he curled himself around the boulder and began to gently and methodically lick it all over.

My host noticed my startled fascination and explained to me that Roosevelt loved his rock and that retrieving it and grooming it were just “what he does.” He plucked me from the sofa and instructed Roosevelt to stay as we took the rock and trundled off deep into the cornfield. When we returned, Roosevelt stretched, stood up, and sauntered into the stalks. A few minutes later, he was back, nosing his rock across the yard.

I was sunk. In that moment I knew a Roosevelt was in my future.

The Great Dane “farm” I located just north of Memphis some four years later, after I’d moved from Chapel Hill to Oxford, Mississippi, to open City Grocery, my first restaurant, was perhaps one of the most disgusting places I’d ever visited. There were two sharecroppers’ shacks, fenced in, floors strewn with threadbare mattresses and half-consumed rawhide bones. Six or so families of Danes occupied the two shacks and the crawl spaces underneath. A four-hundred-pound potbellied pig named Pickles and the knowledge that I had to rescue one of these dogs from the horror in front of me were the only things that kept me from fleeing.

This is how Calpurnia came into my life in 1992. She was a scrawny, dehydrated blue merle. By traditional metrics she was, well, kinda ugly. She sought me out. I knelt. With giant ears slapping against her face, she climbed all over me, begging to go home. Which is exactly what we did.

We climbed into the cab of my 1964 Ford F-100; she curled up sweetly in my lap, then released a flood of super-ammoniated urine. It would be the first time I thought I saw her smile. Over the next twelve years, we were inseparable.

At eighteen months, Cal bred herself with a particularly willful and shitty-acting chow named Punch from down the road. That union resulted in precisely fifteen puppies (who all, thankfully, looked and acted exactly like their mother), and eight weeks later, when I loaded them into the truck, drove to the Oxford Square, and parked on a corner with a giant sign reading “FREE PUPPIES,” I immediately rocketed to the top of the asshole list with fifteen sets of local parents.

Cal made countless trips to New Orleans with me to visit my family. We stayed together at the Soho Grand, in New York, just because they allowed pets. We spent nights at the local arts theater in Oxford, watching Pulp Fiction over and over because the owner allowed—no, encouraged—pets. Cal loved everyone and was loved by everyone with whom she came in contact. She was such a fixture around town that I was as much known as her dad as she was my dog.

Her manner was genteel. She was as gentle as a lamb with children, and her favorite place was beside me in the kitchen, leaning firmly against my thigh. I did not cook special food for her, per se, but I always fed her from the table. She ate everything I ate—except shrimp, which she hated. Once, she managed to abscond with and consume an entire roasted chicken. And then there was the time she got into a massive pile of fermented corn mash and ate herself drunk. When City Grocery was closed, she would come and sleep in the sun under the skylight just outside of the kitchen.

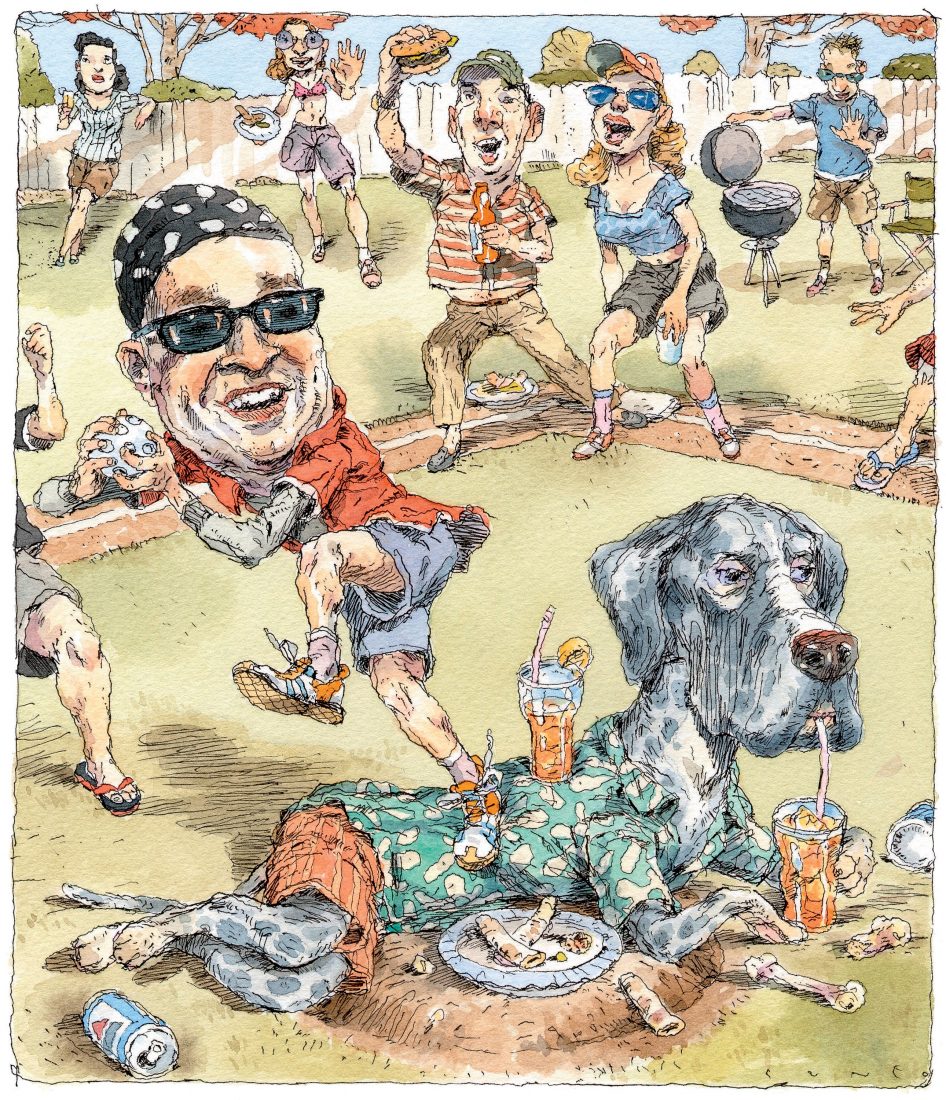

At our annual staff party in the summer, we played an enormously intoxicated game of beer Wiffle ball. There were regularly twenty-five or so people on a side, and music, guns, and fireworks were no strangers to the event. Every year I stood in the infield and pitched to both teams. Every year, Cal lay on the mound at my side, entirely unfazed by the activity.

As the years passed, she got heavy, topping out at almost 180 pounds. Her hips weakened, and winters got hard. She got to the point that I had to help her onto the bed every night. The last couple of days she was with me, she couldn’t stand.

In the end, she suffered heart failure. I had never euthanized an animal and never dreamed of the torrent of emotion that would come along with it. The vet left the two of us alone for a few minutes to say good-bye. The room could not have felt any more insensitive or sterile—the odd blend of bleach, urine, and alcohol on the air, a bad ballast flickering a fluorescent bulb, the icy cold of the stainless table on which Cal would draw her last breaths. I cried like I had never cried. I told myself it was for the best and hugged her as hard as I ever had.

The vet administered a sedative that quickly put her to sleep and then a shot of potassium chloride. He left the room. I held her, sobbing. Her heart slowed, her breathing got shallower, and then she was gone. The silence was deafening. I sat with her in my arms, part relieved she was out of pain, part riddled with guilt, and part feeling that a piece of my soul had been sucked from me. For a moment I was aware of nothing. I felt like an empty vessel.

I remember noticing that her tongue hung limply from the side of her mouth and then that my chest ached. I composed myself, and a clinic assistant helped me move her to my truck so I could take her to be cremated. We placed her on the tailgate, and the young man touched my shoulder to tell me she was the clinic favorite. The receptionists had gathered in the break room and hugged each other when they heard the news.

He asked if I was all right and left me. As I went to adjust her into the truck, I felt a familiar feeling in my lap. She would go out of my world as she had come in, releasing her last bladder full down my front. It was a bittersweet moment. I went about trying to situate her and ignore what had just transpired, but as I moved her into the truck and I turned her around, I couldn’t help but notice her smile.