Driving toward Dallas, I began to write his obituary in my head. There he was, in the rearview mirror, starting to notice the landmarks that point the way to the vet’s office. He laid back his ears. He hid his paws. He probably thought it was another nail trim, his least favorite kind of outing.

I worried it would be much worse, and my eyes welled up.

Our home is quieter, a little less hairy, and a lot less cuddly today, I’d write on Facebook with an appropriate selection of photos from his better days. By God, Woodrow, it’s been one hell of a party.

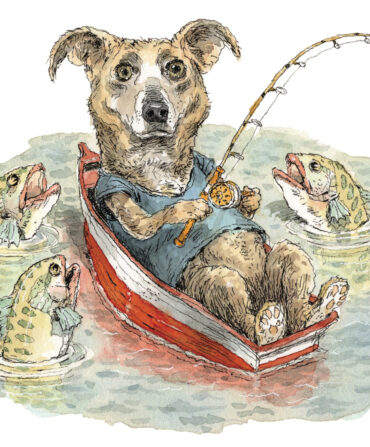

I’d named him after the Lonesome Dove character even before I’d officially signed the adoption agreement from a Dallas shelter. It had been my favorite book in college, although he’s probably more of an Augustus, in retrospect. I was in my mid-twenties then. So was he, in dog years. He had been passed from temporary home to temporary home before I saw him on the shelter’s website. Part red heeler, with red and white spots and big floppy ears, and part German shepherd, I thought. (Even at more than sixty pounds, he thought of himself as a lapdog.)

Woodrow was my first test of keeping something alive other than myself. I had succeeded so far, but if I suddenly lost him, how could I expect to take care of anything else? Had I failed as a pseudofather?

I was a bachelor when I adopted Woodrow, and my pad was tidy but certainly not spacious. When I came home from a bad date, he’d be there to tell me it would be okay. I was a rookie reporter at the Dallas Morning News, and when I had to rush to the office to cover late-breaking events, he’d always be there when I staggered back early in the morning, ready to snuggle. He was my copilot, riding shotgun on long road trips all across Texas.

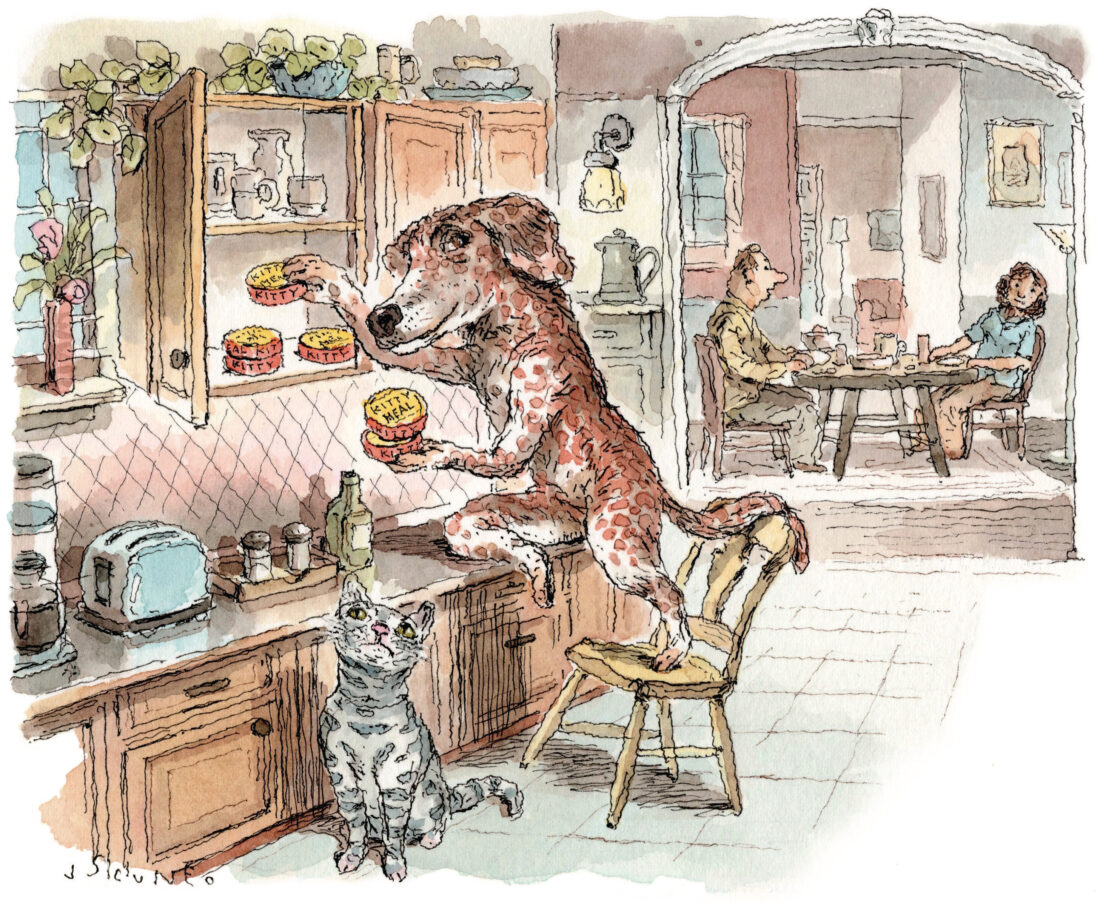

Then I met Hanna, and she moved in with us. When we found an injured tabby kitten, Oliver, he moved in with us, too. Hanna and I called the pets “our two boys.” They fought as brothers do, wrestling and chasing each other around the house.

Woodrow had his first big health scare after Hanna joined the household. He was running around a friend’s backyard when we heard something pop, and he screamed like a car alarm. He lay on the ground, unable to stand. The vet said it was his cranial cruciate ligament, akin to a human having a torn ACL. The best treatment, the vet said, was an expensive surgery.

I first had the Talk with his vet then. Would Woodrow be able to run and play again? Would the surgery and long recovery cause more pain than it was worth? She assured us he still had plenty of good years ahead, and Woodrow got a brand-new, $5,000 knee on credit.

He wasn’t quite the same after that. His new nickname was Old Man Pooch because of the way he strained to reach up onto the couch or groaned when he flopped onto his bed at night. He seemed to be entering a new phase in his life. I began to realize he probably had fewer good days ahead of him than behind.

My life changed, too. Hanna and I got engaged and were married. We all moved to a little brick house with a big backyard in Arlington, just along I-30 from Dallas. Before long my mid-twenties became my late twenties, and Hanna and I started talking about a bigger family as we both entered a new decade.

The day after my thirtieth birthday, Woodrow wasn’t interested in eating dinner. That night, he wouldn’t stop panting before bed. For what felt like an hour, I lay on the floor next to him, trying to get him to relax. The next day, he didn’t move much and vomited pale yellow bile. When I called his name, he lazily lifted his tail but didn’t get up. I sat next to him, tried to pet his chest, and he whimpered. He’d never been in pain like this before, even after the knee surgery. “You should call the vet,” Hanna said. “See if you can get an appointment today.”

I had already Googled his symptoms when his breathing had started to slow. All the possible outcomes seemed awful. The treatments seemed too pricey for a senior mutt, no matter how good a boy he was. Would they make the decision right then and there? Or would we get to go home and think about it? Would Hanna be able to make it in time? Or would we be able to give him one of those great last days you see in tear-jerking viral videos?

During the height of the pandemic, the vet’s office became strictly curbside-service-only, with no human customers allowed inside the building. A veterinary technician had to carry Woodrow in like a baby, all sixty-three pounds of him. The technician told me to wait outside, that the doctor would call when she had a chance to see Woodrow.

The phone rang a few minutes later. I told the vet what I remembered from the past days. Woodrow’s lack of appetite. His lethargy. How he winced when I tried to pet him. As I waited for the vet to run tests and take X-rays, I saw another technician carry out a blue bag with silver lettering: “Faithful Friends Pet Cemetery and Crematory.” I couldn’t imagine our Old Man Pooch fitting in that little blue bag.

My phone rang again. The test results were negative. The X-rays looked clear. Was it even more serious than I’d dreaded? What terrible, unknown ailment could it be?

Gas, the vet said. A case of really bad farts.

It was the cat food he’d stolen a few days prior, which he sometimes ate if he knew we weren’t looking. Since he’s a senior dog now, the strange snack made him feel sick—and convinced me he was on death’s doorstep. He’d be fine but needed an anti-nausea injection and prescription food for a few days. After the tests, medicine, and emergency vet visit, it was a $500 tummy ache.

The worst is still yet to come, I know that, and I’m learning now that taking care of an older dog isn’t just about playing fetch and belly rubs. It’s about knowing how to weather the terrifying times alongside the good ones.

That may be the biggest lesson my fur son can teach me before a real one comes along this spring. Ever since Hanna carried that little blue-and-white stick with the digital readout into our bedroom a few months ago, I’ve been obsessing over every little detail of being a good father. I’ve bought stacks of books, downloaded apps, listened to podcasts. There’s a lot of excitement, but also moments of panic when I think about how woefully underprepared I feel to take responsibility for another human being.

But then I look over at Woodrow, who reminds me I do have what it takes. When he came out of the vet’s office that scary day, he bounded toward the car and hopped in the back seat as he did on our bachelor road trips. It’d be another couple of days before he was completely back to normal, but he already had a big grin on his face as if he’d pulled some wonderful prank on me. “By God, Woodrow,” I said as we drove back onto the interstate toward home. “Hell of a party.”