Hillary Waters Fayle slowly turns a magnolia leaf over in her fingers, coaxing a needle threaded with embroidery floss gently through to the other side. “It’s all about the connection between creation and the human hand,” she says. She means this metaphorically, but she’s also speaking literally: Stitching intricate patterns onto delicate leaves takes a meticulously soft touch. “I’m asking a material to do something it’s not supposed to,” she says. “Even though I’ve done it so many times, I look at a finished piece and think, I can’t believe I got through without tearing it.”

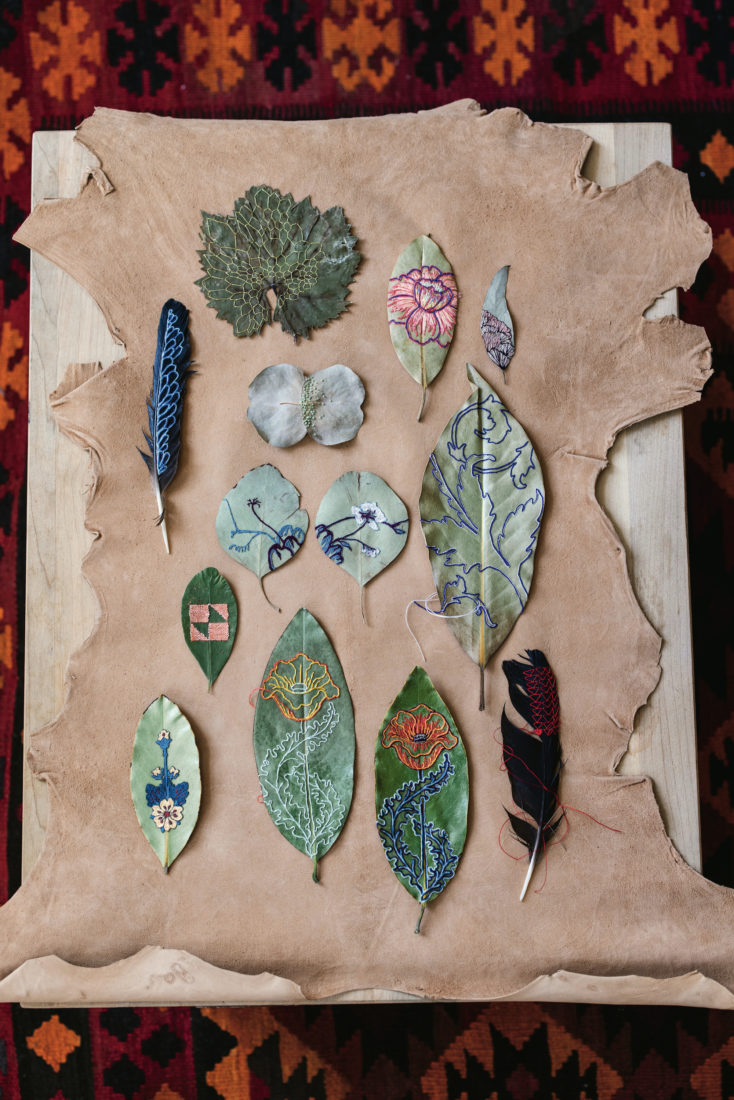

Around her Richmond studio lie finished and midprocess works. A maple leaf with red thread tracing its veins; a eucalyptus leaf bearing tattoos of its likeness in orange and blue; a Ligustrum leaf missing slivers whittled out with an X-Acto knife; two ginkgo leaves bound by geometric stitching. Fayle, who runs Virginia Commonwealth University’s fiber arts program, is quick to point out that the art form is not new. One of the oldest known flax fibers, found in a Georgian cave, is estimated to be more than thirty-four thousand years old. Fayle herself often finds inspiration in historical quilt patterns, lace techniques, and traditional fabric motifs from around the world.

Fayle learned to sew as a child, but her nature obsession began at a New York summer camp she attended as a teen. “For college, I flipped a coin between environmental science and art,” she says. “I landed on fiber design and fell in love.” During a semester studying in Manchester, England, she grew accustomed to stitching on a small scale, tiny works that would fit in a suitcase. Her passions aligned a few summers later when she found herself working as a cook at her former camp. She embroidered between meals, improvising with materials. “I walked outside and saw a big oak tree. I thought maybe I could stitch on a leaf,” she says. “That was the first thing I made that I was really, really proud of.”

Since then, she’s taught at North Carolina’s Penland School of Craft, the Mediterranean Art & Design Program in Sicily, and Yaşar University in Turkey, and exhibited works—pressed on archival material under museum-quality glass to ensure preservation—in galleries worldwide. But most pieces still begin with a neighborhood walk, meanders along blocks with gated gardens and verdant city parks, human and natural history intersecting on every corner. “Anytime someone has planted a seed or picked a flower, they’ve shaped a landscape,” Fayle says. “There are human fingerprints all over the natural world.” Hers included. As she ambles, her eyes fix on the canopy or the silhouettes that have fluttered to the sidewalk. “We’re so used to leaves, we often don’t realize they’re there.”

Back in Fayle’s studio, some leaves get pressed—“very low-tech, between books to get the moisture to even out,” she says—while others go straight to her worktable. She charts a design in her sketchbook, then lays the paper over the leaf, pricking holes with a needle through to transfer the pattern, marking where each stitch should go. Then she begins the painstaking needlework, careful with the pressure she applies. “You have to hold close to where you’re puncturing so it doesn’t break,” she explains. Her most fragile canvases—ginkgo leaves, tree of heaven seed pods, even plumage—can take up to forty hours to complete.

Like foliage, Fayle’s art is transient. “Some leaves fade to be more golden, or muted, some become more minty over time,” she says. “But using organic material is part of the magic for me. I’m confident they will outlast me, but my pieces do have a life cycle. They can’t exist forever.” Just as nature intended.