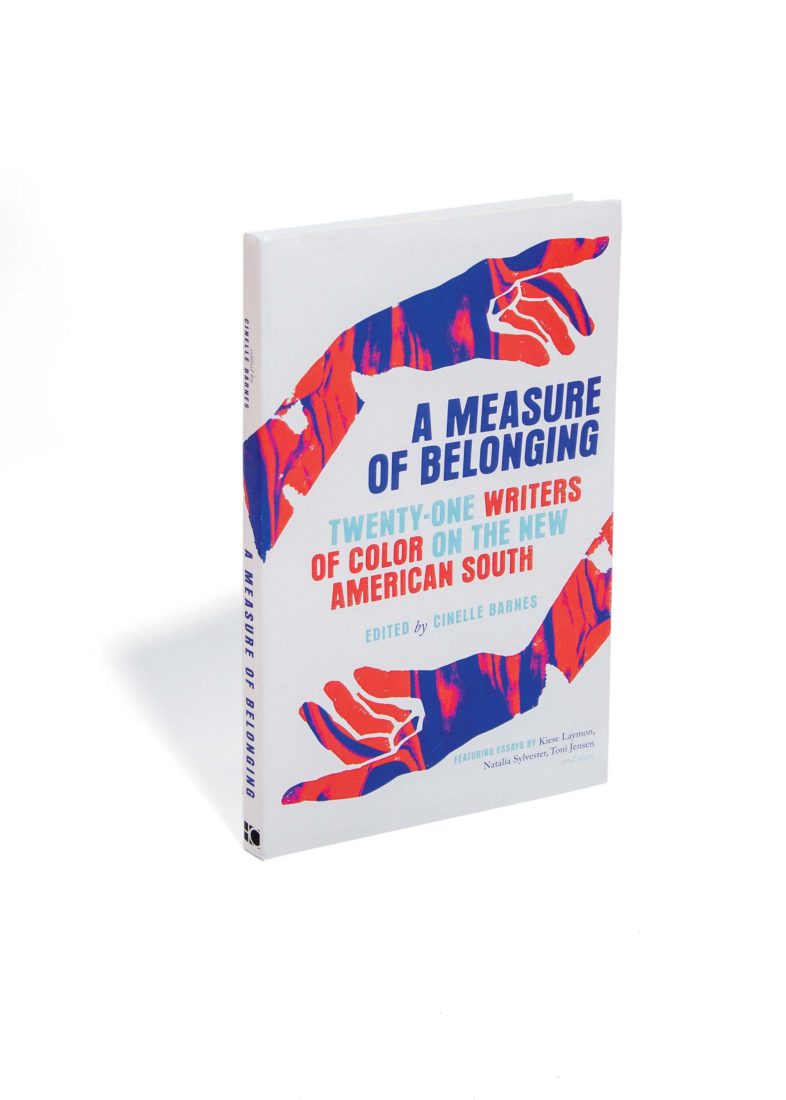

“Not even a geographical place” is how William Faulkner’s Chick Mallison, in Intruder in the Dust, regarded the North, “but an emotional idea.” Mallison may just have well—and more accurately—been describing his native South. Yet even more nebulous, and more emotionally charged, is the notion of Southern identity—especially for people of color. For A Measure of Belonging, a thoroughly timely anthology, the writer and editor Cinelle Barnes marshals twenty-one considerations of what it means to be a Southerner of color. The assembled essayists, most of them young, are African American, Native American, Puerto Rican, Filipina, Peruvian, Indian, and Korean, but all of them—whether by birth, choice, or the whims of fate—call the South home and, more important, define themselves, in varying and sometimes painful ways, as Southerners. These writers realize, uneasily at times, that they belong to the South, from the way they talk to the way they eat to the way they must reckon with what Tom Robbins called the region’s “volatile and sometimes violent idiosyncrasies.” What they aim to make clear is that the South, in turn, belongs to them.

When Barnes, born in the Philippines and raised in New York, arrived in South Carolina a decade ago, some of the hospitality she encountered fell short of what the brochures promised. She did not shrink. “I decided that every one of my projects thereafter would be an invitation for other people of color,” she writes in her introduction, “to come, to be visible, and to thrive here.” The writers she gathered know “how to take up space and make space,” she writes, “in the way that only millennials and Gen Xers know and zealously practice.”

Aruni Kashyap, a novelist and teacher born in India, takes us apartment hunting in Athens, Georgia, to show us the belittling questions and half-hidden suspicions with which he must contend. The poet Joy Priest provides liner notes to the hip-hop soundtrack of her Louisville adolescence, gorgeously annotating the “songs of representation” that “portended a come up for those of us living in American obscurity.” Toni Jensen, who is Métis and teaches in Arkansas, confronts her own ability to “pass” as white after one of her African American grad students is bullied. Other essays probe the liminal areas between the poles of black and white. The author Ivelisse Rodriguez, “a dark-skinned Puerto Rican,” describes being flummoxed at a North Carolina DMV office when asked to select her race. Her choice is Black; the clerk disagrees. M. Evelina Galang recounts the quandary faced by her father, a Filipino immigrant, when practicing medicine in the still-segregated South. The hospital guard directed him to the “Whites Only” entrance. “But look,” her father replied, pointing to his skin. “I am not white.”

Several essays evoke Richard Wright’s agonized line from Black Boy: “I was not leaving the south to forget the south, but so that some day I might understand it.” The most bracing of these is “Treacherous Joy: An Epistle to the South,” from the African American poet Tiana Clark, who shares her longing to return to the Tennessee of her youth. “I thought home wasn’t supposed to hurt,” she writes, “but everywhere hurts to live, so I want to come back home to the hurt I know best.”

That same hurt gets examined, gut-wrenchingly, by the Mississippi novelist and memoirist Kiese Laymon. His essay, “That’s Not Actually True,” resists description and defies paraphrasing. It is a reviewer’s cliché, when assessing anthologies, to deem a single piece “worth the price of admission alone.” But the cliché is true here. Laymon’s sentences land like sledgehammers. He forces you to rethink almost ev-

erything, including, if you’re a white Southerner, a lifetime of interactions.

Barnes’s subtitle is Twenty-One Writers of Color on the New American South. There’s fair cause to be skeptical of every New South iteration that comes along. (Walker Percy may have said it best: “My definition of a New South would be a South in which it never occurred to anybody to mention the New South.”) Yet the South on exhibit here does feel new: polyglot, multiracial, small-c catholic, urbanized, unwilling to accommodate or overlook the past but instead primed to confront it head-on, and keen to sift the South’s virtues—lovingly—from its flaws. Barnes’s goal stands as a one-line manifesto that, as this anthology makes clear, deserves our broadest adoption: “I’ve committed myself to making this place as big as it actually is.”