Planes mostly, but also trains and automobiles deliver an average of 275,000 passengers to Atlanta’s Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport every day. They grab PowerBars and boxed salads from kiosks, hunker down for a few minutes in the food courts over fried chicken tenders and beef lo mein, or knock back a few drinks in one of the nine Delta Sky Clubs. But some of these fliers will find their way to One Flew South, by the top of the escalator on Concourse E, just past the Swarovski shop and across the atrium from the TGI Fridays. With its bottles of spirits visible through a window and its louvered wood walls, One Flew South looks like a high-end duty-free shop. It isn’t. It’s an oasis—an airport bar and restaurant like nothing else on earth.

I’ve been going to One Flew South since its opening party in December 2008, an affair I remember being replete with dignitaries and duck sliders in equal measure. An escort led us partygoers en masse from the main terminal to the restaurant, where the airport’s CEO and tall, dapper Delta suits stood with hands outstretched. I drank excellent cocktails and kept my eyes peeled for the hors d’oeuvre trays, not realizing that we’d all be sitting down for a full meal. As the chief food writer for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, I was getting all the principals paraded in front of me. Terry Harps of Global Concessions and Jackmont Hospitality’s Daniel Halpern, whose companies co-own One Flew South, were there for handshakes and hellos. But the publicist, Elizabeth Moore, was more interested in introducing me to the all-star food-and-beverage team that had been lured away from Louisville’s Seelbach hotel as a unit—executive chef Todd Richards, with his team of Duane Nutter and barman Jerry Slater, as well as Reggie Washington, who had been chef at the Alabama governor’s mansion.

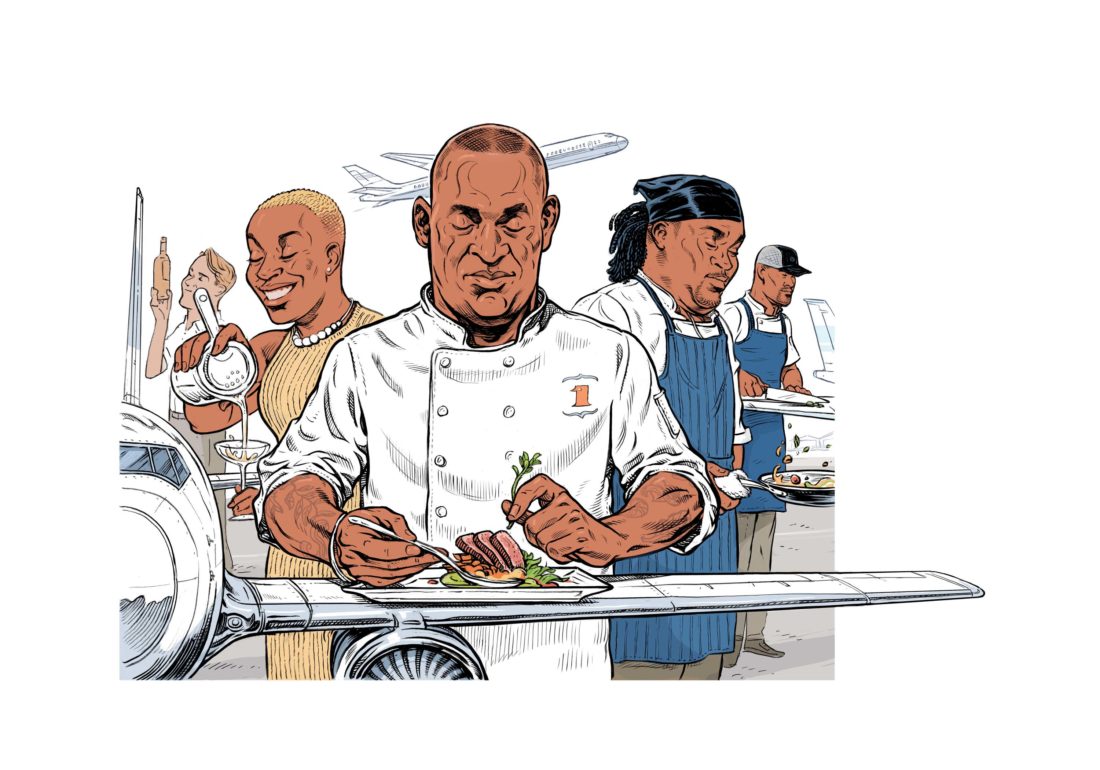

As Richards reminds me every time I see him, I made a terrible decision that night not to review One Flew South. I figured it would be like recommending a country club, a dining experience only available to some. I reported on it for news and trend stories but never took a broad look at its culinary impact. But what an impact it had: This minority-owned-and-operated restaurant was one of the first to reclaim the developing narrative of Southern food from an African American perspective. Richards, who would go on to open several restaurants in Atlanta, set a course for a generation of chefs to follow. Think of Mashama Bailey at the Grey in Savannah and Edouardo Jordan at JuneBaby in Seattle.

More than a great restaurant, One Flew South also had one of the best bars in Atlanta, if not the entire country. After a couple of years, Slater moved on to other projects and Tiffanie Barriere took charge. Here was a black woman with short platinum-blond hair, a brilliant smile, and a voice like

Macy Gray’s. Regulars arranged flights to spend time at one of the bar’s ten seats and texted her when they landed.

“Reggie and Duane and Todd and Tiffanie worked that room like it was the idealized doorstep for the American South,” says John T. Edge, director of the Southern Foodways Alliance and a Garden & Gun contributing editor. “They did something unprecedented: They set a welcome table in the airport. They said, ‘Let us welcome you to our South,’ and their South was black, their South was cool, their South was hip, their South was great.”

PREPARING FOR TAKEOFF

One Flew South opened as a joint venture between two of the larger concessionaires at Hartsfield-Jackson: Global Concessions, helmed by Terry Harps, and Jackmont Hospitality, run by Daniel Halpern. These two men were used to competing for dining dollars at the airport, but here they joined forces. Their publicist, Elizabeth Moore, arranged an ad hoc audition with a chef crew visiting Atlanta.

Halpern: The space was unused ticket counters. When it became available, the airport articulated they wanted a restaurant. Something upscale, but they left us to figure out what it was. What Terry and I really wanted to do was work with an African American chef who could serve Southern food with an emphasis on the African American culinary experience. We’re two African American–owned companies. [Harps is black, while Halpern’s partners

in Jackmont Hospitality are Valerie Richardson Jackson and Brooke Jackson Edmond, the widow and daughter, respectively, of Maynard Jackson, Atlanta’s first black mayor, who founded the company.]

Richards: There was just so much serendipity. They wanted to do a restaurant that featured black chefs. We [Richards, Nutter, Slater, and Washington] happened to be in town for the High Museum wine auction, and we knew Elizabeth from the Southern Foodways Alliance. But mainly we were trying to leave Louisville and get back to Atlanta.

Moore: Todd and Duane came and cooked at my house while Jerry made cocktails. I remember having to explain to Terry and Daniel what a James Beard Award was.

Richards: Duane and I had been together off and on from the time of Chef [Darryl] Evans [the African American former head chef of what is now the Four Seasons Hotel Atlanta, where the two chefs met in the late 1980s]. We’ve always had this rapport from growing up in the kitchen together. Maybe it’s that I’m left-handed and he’s right-handed.

Moore: We all got together for this three-day naming exercise in a private room at a client’s restaurant. We had these little sticky notes all over the walls. We had a bunch of aviation terms, but they all seemed really dry and definitely didn’t speak to what we were trying to do. I came up with the name. I was thinking about how one would tell a story or share a memory: “That one time when I flew South…”

Halpern: In early meetings with the airport, they suggested we use materials indigenous to the region. Working with [Atlanta restaurant architect] Bill Johnson, we got Georgia Cherokee marble for the counters, and heart pine reclaimed lumber for the wood slats we used instead of walls. People walking by the slats could look inside to see the forest mural along the back wall. Some thought it was a private club.

Richards: After we signed on, we had only a couple of months [before opening]. The restaurant was already in construction, and, honestly, the line wasn’t set up to be the most efficient. We had to make some adjustments, also to our style of cooking.

Nutter: All the knives had to be chained to the workstations—they were tethered to the tables like dog leashes [due to airport rules]. I had to keep a drill in my tool kit for when we needed to swap them out.

Slater: We did this soft opening, and the owners invited all the Delta executives. But they really overinvited, and it got crazy that night. One of those Delta guys came into the kitchen while we were trying to get the food out and asked why the Benton’s bacon—you know, it’s an artisanal product—looked different on sandwiches. Duane was so in the weeds and he just said, “You’re going to have to go back in the dining room and take that shit up with Jesus.”

Richards: After all the media parties, we got feedback from the Department of Aviation. They said they had never seen anything like this.

RAREFIED AIR

This unusual mixture—high-end spirits, upscale Southern fare, and a sushi bar—caught on immediately in 2009 with airport executives, frequent fliers, and the press.

Moore: After Todd and Duane developed the first menu, I remember thinking nobody quite knew what to do with it. I mean, they had this Lowcountry bouillabaisse and I was thinking, “How do you sell an eighteen-dollar soup in an airport?”

Richards: We [had been] doing high-end stuff [at the Seelbach]—foams, molecular gastronomy. We toned that down, but still we showcased a repertoire of dishes. A pork belly dish we made for Daniel and Terry at the tasting ended up on the menu. We were serving duck and fresh fish that we broke down every day.

Nutter: One time I was trying to break down this big ole fish—it was about five feet long. I kept going at it and cutting myself and finally realized I had to unscrew [the knife chained to the table]. It would have been a ten-thousand-dollar fine if the inspector came in then. I did get busted once. Some new guy showed him where I kept [knives] hidden in the ceiling tiles.

Slater: A lot of the guests at that time were European [Concourse E was then the international terminal], and they got what the food and drink was about right away. We had to add gratuity to the bill because Europeans don’t always tip. But people had no problem spending $150 on a bottle of wine.

Moore: They ended up doing triple the business they were expecting. Soon after we opened I was sitting at the bar next to this German dude, and he was trying to figure out what to order. I suggested he try the 23-year-old Pappy Van Winkle, which was fifty bucks a shot. He didn’t blink an eye.

Slater: We had come from Kentucky, and I knew Julian [Van Winkle, the master distiller]. We ended up getting two bottles of everything in his whole line to open with. That really was pretty rare. But it wasn’t just the Pappy. Everything had to be curated. We believed that people would get it. Maybe they got it a little too well.

Nutter: Bosses would come by to see why there were always expense reports for this place. A Delta executive came out to say everyone is changing their flight plans to come here. It was kind of like Cheers, but nobody was from Atlanta.

Richards: There were people who became huge fans right away, and there were some detractors. One lady complained when her BLT went off the menu, and I had to tell her, ‘I’m sorry, it’s not tomato season now.’ She just kept checking in every time she came through Atlanta.

Barriere: It was insane the amount of business we were doing. We had only ten seats, and usually about 80 percent of the folks there were bar regulars. If I really loved you, I’d let you sit at the service bar.

Maggie Howes [who became a regular customer in 2010]: I live in Key West, but I’m a veterinary consultant, so every week I fly all over the world, and I stop in One Flew South two to four times. I remember there were two people who came in and got pretty inebriated. They didn’t know each other at first, but after forty-five minutes, they walked around the corner and started making out. But the main thing was everyone sitting there had a rapport with the bartenders and each other.

Barriere: We’d see the same people Mondays and Wednesdays and then Tuesdays and Thursdays. There was a couple who met because they would both order chicken noodle soup. I made cocktails for them, and soon they were getting really flirty. They’d plan to meet at the bar. They stopped coming for a while and I was worried. But then they came in with a baby, which we named Chicken Noodle Soup.

Howes: Pretty quickly [Tiffanie] became part of what I consider my travel family—the gate agents, the Delta lounge folks. I see them more than people at home. It’s like having a bunch of crazy brothers and sisters who also bring you good food.

Nutter: There was the one guy who never sat, so we knew to move the chair away for him before taking him to the table. Then there was the guy who always came in for the scallop dish. One time a manager, Brad, had to tell him we had taken it off the menu. “That’s the wrong answer, Brad!” he said. And from then on he was known to all as the Wrong Answer Guy.

Barriere: I had a lot of celebrities come to visit. Mos Def, Ludacris, Usher, Samuel L. Jackson. Laurence Fishburne was a really cool dude. Nicolas Cage did this full spin, hands in the air like, ‘Look, I’m here, everybody!’ Robin Givens came, and we got her really drunk. The one I was most excited about was Ric Flair, the wrestler. And we had several parties. We did several birthdays. Even a bridal shower.

Nutter: The menu took a big change when Concourse F [the new international terminal] opened. I realized I couldn’t run foie gras specials no more, because I now had Spirit Airlines next to me. I got to switch up a few things. Hello, meat-loaf sandwich.

IN FOR THE LONG HAUL

By 2016, much of the original crew had flown the coop. Nutter and Washington left to open Southern National in Mobile. Slater now co-owns the Expat in Athens, Georgia, with his wife, Krista. Barriere works as a brand consultant in the spirits industry. Richards has authored an award-winning cookbook (Soul: A Chef’s Culinary Evolution in 150 Recipes) but still manages the culinary team at One Flew South, which remains busier than ever. According to Halpern, it brings in about $6 million in revenue per year. The chef for the past two years, Cedric McCroery, grew up near the airport in East Point, an Atlanta suburb.

McCroery: There were so many things going on in this kitchen that I had never seen before anywhere in my career. I started on the grill side, then went and worked the sushi bar. I seriously never thought that would be a skill I could add to my repertoire. But my goal was to come here and learn. What have I learned? That you can tell a story through food.

Richards: Right from the start it felt groundbreaking. How many restaurants have been this successful for ten years?

Nutter: We took a whole different approach because we came from a fine-dining background. We looked at these customers for who they were. It’s just a different group of people who travel for a living, and for them we were a respite.

Howes: There isn’t anything like One Flew South anywhere in the world. Not in Dubai, not in Japan, not in Germany, definitely not in the United States. I’m a Southern girl, and I have a good appreciation for hospitality. Maybe that’s it, that little bit of Southern tradition, that Southern hospitality that sets this place apart.