“It’s really inconvenient and I’ve tried to change it and it just doesn’t work,” says Charles Frazier of his writing routine. “I don’t start feeling very creative until up in the afternoon— about three o’clock is the start of my workday. An ideal day is I sit around drinking coffee and reading books for a couple of hours and then run some errands and then go for a bike ride or a walk. Then it’s like an alarm clock goes off. If I’m not at home getting ready to get up at my desk by three, I start getting antsy.”

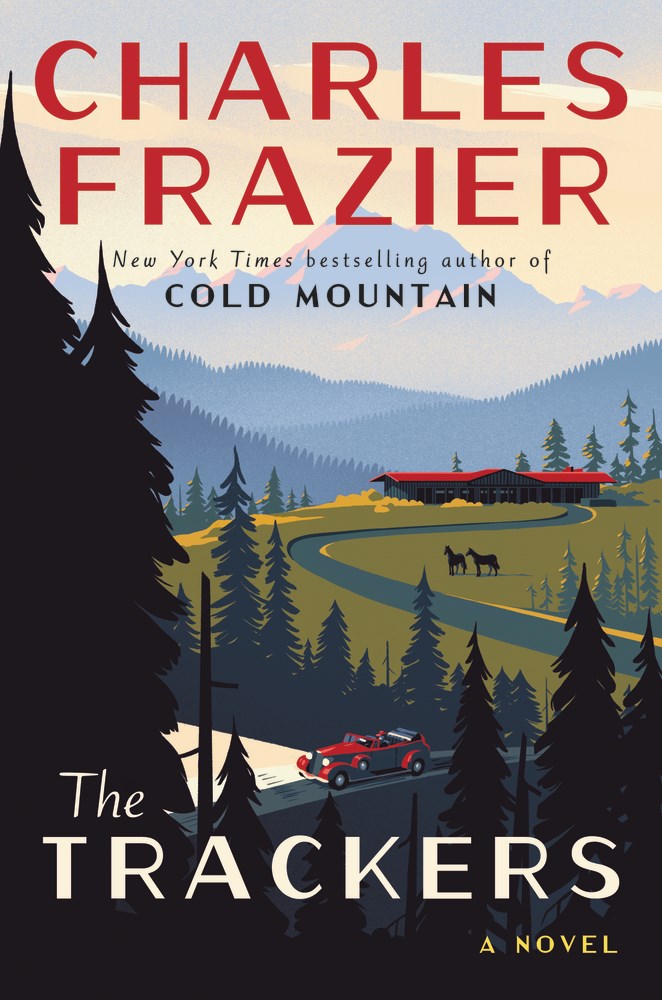

This might be one of those “if it ain’t broke…” scenarios, as Frazier’s writing routine has solidified him as one of the living greats of Southern literature. Frazier is best known for his 1997 debut, the Civil War–set Cold Mountain, which went on to top bestseller lists, win the National Book Award, and become a film starring Nicole Kidman and Jude Law. His later books, including Thirteen Moons, Nightwoods, and Varina, were also set in Western North Carolina, Frazier’s homeland. His latest novel, The Trackers, takes his characters farther afield during the Great Depression: out West, to San Francisco, and to the Gulf Coast and Florida (Frazier drew inspiration for that section from his own experience owning a horse farm—a refuge for retired show horses—with his wife in Central Florida around Ocala National Forest). Here, the author shares some of his favorite North Carolina memories, how a photo inspired his new book, and what he really thought of those Southern accents in the film adaptation of Cold Mountain.

Where did you grow up in North Carolina?

I was born here in Asheville, in Biltmore Village in a little hospital that was designed by Douglas Ellington, who did the S&W building and some of the other iconic Asheville buildings. But I mostly grew up in Andrews, which is even farther out there. My father got a job as a school administrator in Franklin, so I was also there for two years at Franklin High School. We came over to Asheville every other week. Asheville was the city, and it has always felt like a little city, all broken up in different sections of downtown, weird little corners and all that. I always loved it. When I would come up with my friends from Andrews, I got to be Mr. Urban Sophistication. I knew how not to get lost.

You described your perfect day as including a bike ride—what are some of your favorite spots to bike around Asheville these days?

The place that everybody goes because it’s close is Bent Creek. But over in Pisgah Forest, there’s loads of trails and I do some of those when I have time for the drive. DuPont Forest has tons of trails, and these are good for hiking too. Sometimes I’ll ride around Biltmore Estate, just along the river and on the trail that goes up the back side of the house.

You were in academia for a while before writing novels. What were some of your early jobs before that?

I worked at least two, maybe three summers on a large old-fashioned farm in the Cowee Valley [North Carolina]. They had tomato fields, tobacco, and there was a lot of hay to bale up and put in the barn. Just old-fashioned farm work before everything was so automated. My good friend and I, we were always up for it. We didn’t want indoor jobs. We joked that we’d do anything for a dollar an hour. I worked on two houses around Franklin too, carpentry. Back then it was different because you had a builder who did almost everything. So it wasn’t like there’s this contractor and that contractor. We did everything from pouring the foundation to putting in the kitchen cabinets.

Oh, and the worst job—do you know that place Gold City? They found an old cave on the side of the mountain, and they were going to let people go in and out of their “old moonshiner’s cave.” A friend of mine heard about a job there, but it was cleaning out the cave. There were like three of us working. We lasted two days and had to get the hell out of there. What I wanted was the “gunfighter” job at Gold City, but I never quite made the cut. A friend of mine in high school who got it, he looked like he was forty years old when he was eighteen.

I promised my mom I would ask you this: There’s this character in Cold Mountain, the goat woman who helps heal Inman. Was she based on someone you knew?

Yeah, the character itself was partly based on a friend of ours, of my mother’s, in Andrews. She did not have goats. [Laughs.] But she had a garden and did a lot of canning and putting up and all that. She was just a hilarious person to be around, she was so funny. She knew all the stuff, like what days to get things done. When I had my tonsils out, they were taken out according to the signs. She would always tell us what blocks of days to get what done, but don’t do it on these other days because you’re likely to bleed to death. My younger sister would just say, “I’m sick, I can’t go to school,” and my mother would take her down there to spend the day. There are bits of her all over my writing. It’s that kind of old knowledge that she had a lot of. And an old sense of humor that had a huge amount of irony in it.

That’s a thread in a lot of your books, of old ways and new ways colliding. The new book The Trackers reflects that theme.

It started with a photograph. I’ve always been interested in the federal projects from the Depression, especially the public art stuff. At least ten years ago, we were up at Appalachian [State] for something, a horse show or something, and I was killing time. I saw this picture in the library that showed a mural in the works in a small post office. It had mountains and horses and cowboys. There were two youngish guys on a scaffold and a somewhat older man and woman dressed up on the floor looking up. I thought about it, and I did some more reading about the WPA [Works Progress Administration]. And then I did another book. And when I got through with that one, I came back and I was still thinking, who are those people? Where are they? Why are they there? What are their relationships to each other? And I just started working with that.

When I was a kid, every adult had a Depression story or had some little something they did that reminded you that that time was still with them. You know, like people who would use a piece of aluminum foil and wash it and spread it out and reuse it. I tried to just connect to some of those childhood memories of how the adults talked about the Depression. There’s also a really good book that shaped a lot of my thinking about teenagers in that time. It’s got the somewhat odd title of Boy and Girl Tramps of America, by Thomas Minehan. In the 1930s, he was a graduate student who went out and traveled with teenage hobos. He got tons of wonderful stories, and it was out of print, but the University Press of Mississippi just republished it.

The characters in The Trackers travel to the Gulf, to San Francisco, and out West. Was that a bit of a departure for you?

I’d been going out [West] from the time I was pretty young. I went every summer, because my father loved it out there and he was the school administrator at a time when they had big chunks of time in the summer. Little towns out there like Lander and Rawlins, Wyoming. I think Rawlins is where my father’s uncle lived. He looked like a little old cowboy, a short man with blue jeans and a cowboy hat on.…And [my wife] Katherine and I lived in Colorado [in the eighties]. One time [around 1989] I had maybe a month that I didn’t really have to do anything. I did this long, slow drive in northern Nebraska and then ended up in the Tetons. That’s where I wrote the first bits of anything that became Cold Mountain.

What does your family think about the movie version of Cold Mountain?

I think mostly they liked it. And I liked it, but I kept in mind, you know, the book’s mine and that movie was Anthony’s [director Anthony Minghella].

He treated me so well. I’ve done some of those onstage roundtable discussions where writers who have been adapted start out saying something like how their work was so disrespected, and they’re getting these big laughs. And then it’s my turn, and I’m like, gosh Anthony treated me so well, we became friends, he sent me every draft of the screenplay, we met in London, and in Rome, and this, that. He came to Asheville over and over, and we hang out up here. And it’s like, yeah, that’s such a letdown to people. [Laughs.]

I went over to Romania where a lot of it was filmed. I got there, and the scale of it was just pretty incredible. They had used the Romanian army for the battle scenes. I walked down to the set the first day, taking it all in, and I said to Anthony, “I guess a lot of people would look at this and think how powerful you are, and I look at this and think how vulnerable you are.” And he was like, uh-huh.

My daughter [Annie] did work on it, she was there a good while. And one of the things she did was, they’d be setting up a shot, and Anthony would say, “Annie come over here, look through the camera, does that look like Western North Carolina?” She’d say, “No, but if you turn it this way, this kind of looks like it.”

There’s a scene inside a store and there’s a woman who comes up and…again, how respected I was—I went up to New York to watch some of the early edits. And Anthony said, “What do you think of the accents?” I said, “There’s one, that woman in the store. She has it made. She has it.” And he just said, “Yeah, she’s from Waynesville [North Carolina].”

Frazier’s current book tour includes stops in Mississippi, North Carolina, Alabama, South Carolina, and Georgia—find more details here.