Charley Crockett’s life sounds a bit like the script to a Western or maybe a Highwaymen song: He was born in a trailer park in the Rio Grande Valley community of San Benito, Texas, lived the later years of his childhood with his single mother in Dallas, and after tumultuous high school years, spent the next decade developing his music the hard way—busking on the streets of New Orleans, Memphis, and New York City while sleeping in abandoned warehouses and parks. But in 2014, he left that life behind and returned to Texas to officially launch his music career.

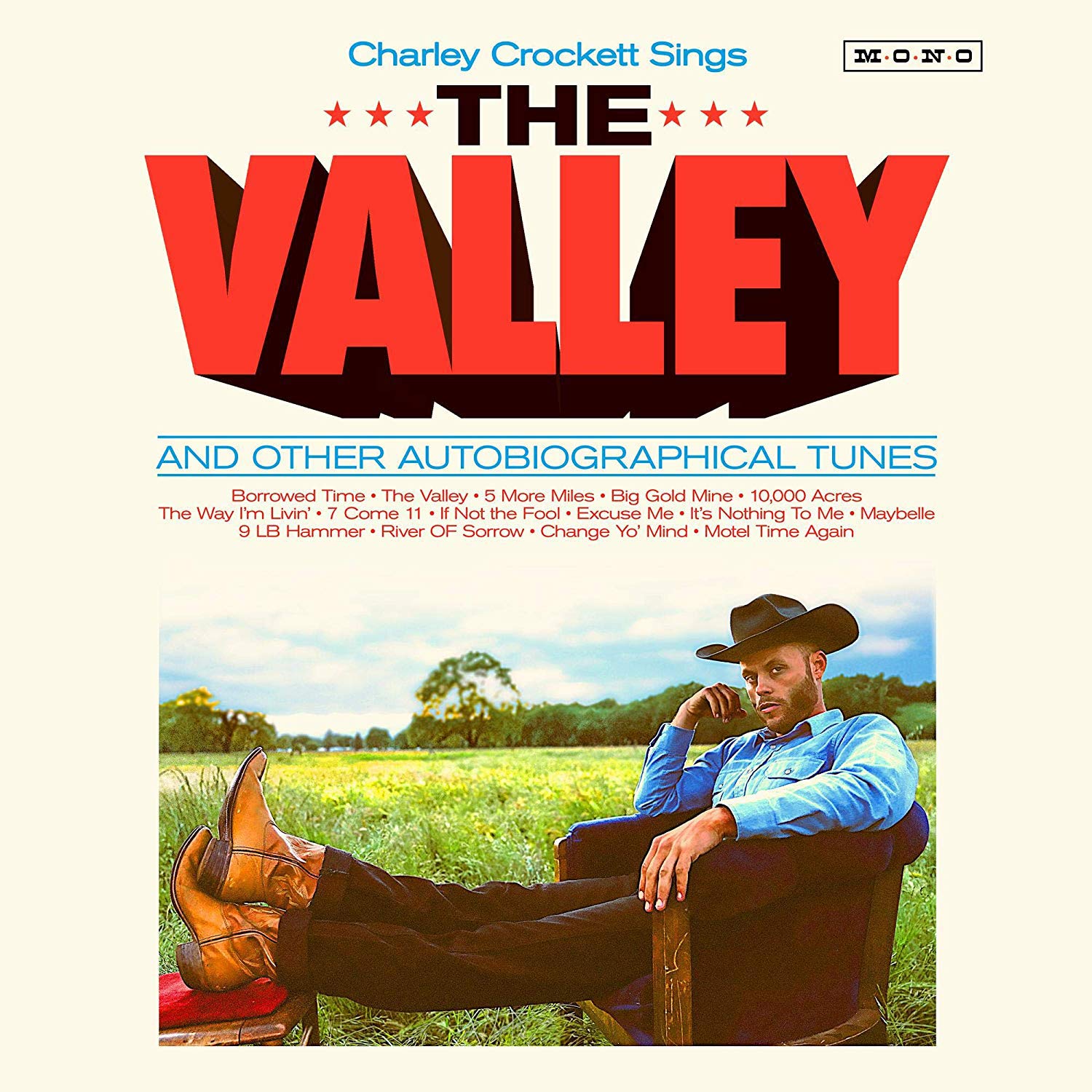

Musically, the thirty-five-year-old intermingles country, folk, soul, jazz, and honkytonk blues, recalling past greats such as Ernest Tubb and Lefty Frizell, but with his own modern edge. Since returning to Texas, Crockett has played with the likes of Leon Bridges and Turnpike Troubadours, and this past June, he made his debut at the Grand Ole Opry. But he almost didn’t make it to the Opry stage. In January, doctors warned him that complications from a rare heart disorder would lead to heart failure within a year if left untreated. A week before undergoing a life-saving surgery, he recorded his new album, The Valley, which comes out this Friday and is comprised of fifteen original and deeply autobiographical songs.

Now fully recovered, Crockett just completed a European tour and is headed back to the states for a string of shows this fall, beginning in Athens, Georgia, September 28. We caught up with him to talk about his Texas upbringing, developing his unique sound, and why he refuses to slow down.

You recorded The Valley the week before undergoing surgery, and it’s incredibly personal. Why was it important for you to tell these stories?

As I’m getting older, I want to leave more behind. I was trying to make an album that would really tell my story more than anything else. When you’re going through all that kind of stuff, you think about honesty: What’s honest and true for me versus the desire to be successful or be appreciated by whatever the music industry is. When you’re facing your mortality, it tends to make you go back and find your essence.

So many of your songs deal with the idea of moving around.

I became an itinerant musician and started hoboing around in my late teens, so I’ve learned a lot from being on the road and being in uncomfortable situations. Relying on the kindness of strangers to let me do my thing, play on the street, find places to sleep at night. But the funny thing about doing the street thing and then going into fulltime touring is they’re actually very similar lifestyles.

Even though you’ve spent so much time traveling around, your home state of Texas seems to have had a major impact musically.

Good Lord, Texas. In the cities, you have this convergence of these different cultures: urban city blues, Tejano music, the Cajun and Creole that bleeds in from the southeast. I think anywhere I’ve gone in the world, Texas carries a lot of weight. When I was younger in hard times, I really tried to run away from Texas, which I think a lot of young people do. But as I got older, I came to an acceptance of how much this place had made me who I am. One day I turned a corner from running away to embracing and being proud to represent the heritage of Texas. I’m related to Davy Crockett—being born with the last name, it puts a lot of responsibility on me as a Texan.

Photo: Lyza Renee

Charley Crockett at the Kessler Theater in Dallas.

Your sound is so different from most everything coming out these days. How did you develop it?

My mama got me a Hohner guitar out of a pawn shop in Irving, Texas, when I was seventeen, and I just started messing around on it. I’ll never forget the first stage I ever got on was at a place in Dallas called the Balcony Club. It was this little five-by-five stage, and I was playing all these weird little songs I’d been trying to write. This guy who had let me on stage and was backing me up asked, “What are you calling this music?” I said, “I have no idea what it is,” and he said, “Well, I’ll tell you what it is. You’re playing the blues!”

Later, I was playing on the street in New York City one day. Somebody showed me this book of T-Bone Walker chords, and I realized I had accidentally found them naturally myself. T-Bone Walker was from rural Texas and went up and made his mark in Dallas, and then he changed the world with blues music. I’m not saying I’m anywhere near as good as that, but it was this acceptance of realizing the place I was from had made me who I was. I realized there was this Dallas blues sound I had naturally been finding, and it seemed like the farther from home I got the more I was finding that sound.

Do you have a favorite song on The Valley?

Probably “5 More Miles.” I originally wrote it on a banjo, and when I hear it, I can hear my struggle and can hear this person inside me overcoming it. That’s how I feel about life. We play this game in society that more often than not is made to lose. I can spend my whole life crying about it being house rules, or I can just play my damn hand and keep moving. Because if you stop moving, you get left behind. I get a lot of people always asking me, post-surgery, why I’m still working so hard. But if I slow down now, then I’ve got to answer to myself.