“A lot of people weren’t sure Dusty in Memphis was such a good idea.”

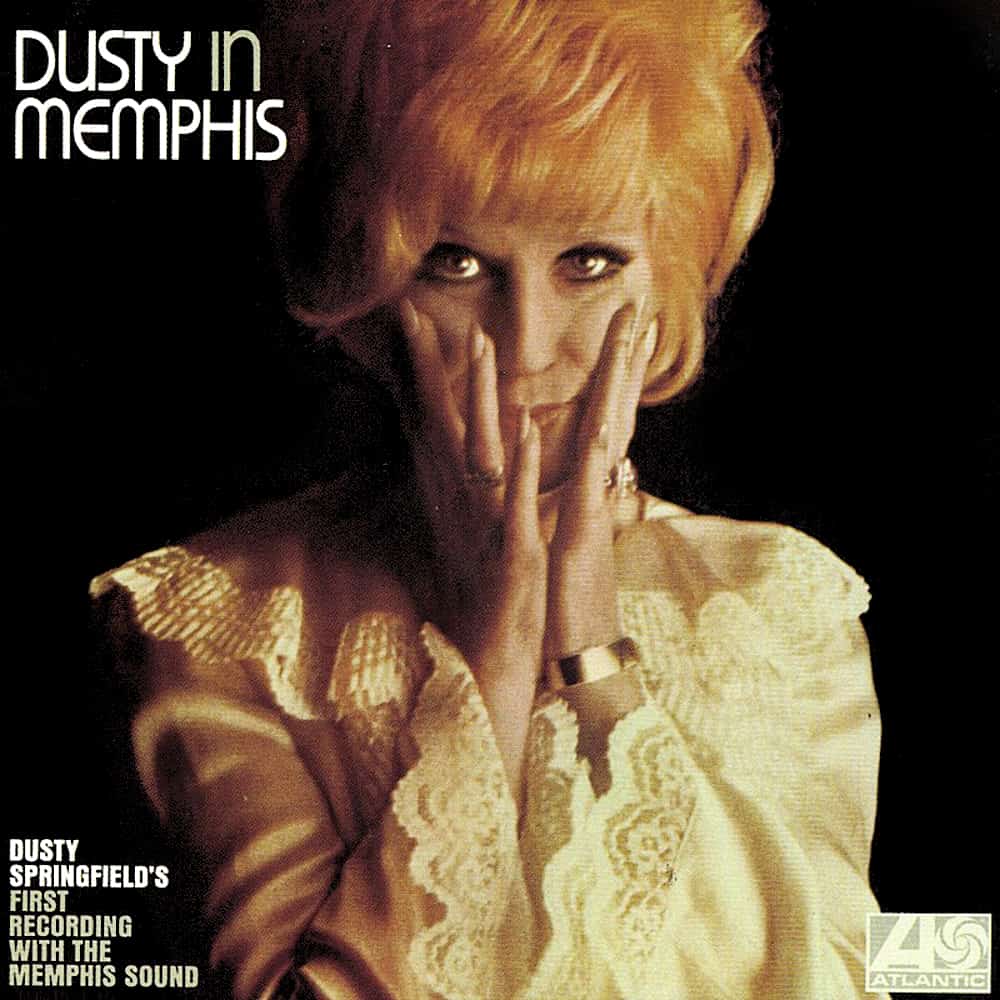

Those words, written by Stanley Booth in the liner notes of Dusty Springfield’s seminal 1969 album, probably sound foolish to fans of blue-eyed soul—after all, the album routinely lands on critics’ best-of-all-time lists, and its lead single “Son of a Preacher Man” has enjoyed decades of international fame. Even before Memphis, the British singer was a well-established hitmaker, having recorded with pop group the Springfields before topping charts worldwide in 1964 with singles “Wishin’ and Hopin’” and “I Only Want to Be with You.” By the time she began plans for recording her first album with Atlantic Records in 1968, the label was prepared to put all its musical might behind its newly signed artist: songwriting heavyweights Carole King, Randy Newman, and Burt Bacharach; producers Jerry Wexler, Arif Mardin, and Tom Down, who had worked with Aretha Franklin; and expert session musicians at American Sound Studios collectively known as the Memphis Cats.

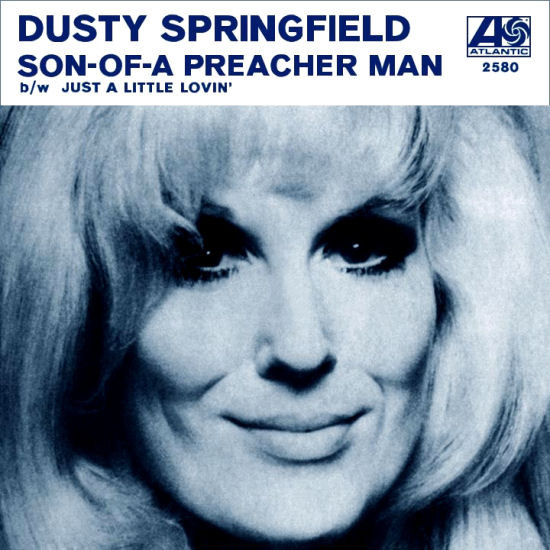

“Son of a Preacher Man” seemed a promising start for Dusty in Memphis. Muscle Shoals, Alabama, songwriting duo John Hurley and Ronnie Wilkins intended the sly almost risqué song about young love for Franklin, but it didn’t fit with what the Queen of Soul was recording at the time, so “Preacher Man” passed to Springfield. The song was her first departure from British pop, and when the song was released as a single in fall of 1968, it reached number ten on the U.S. charts and eleven in Britain, building anticipation for the full-length record set to follow the next year. But the doubters were right—at first. On April 12, 1969, two weeks after its release, the album peaked at number ninety-nine before falling off the Billboard charts entirely, never to return.

How did such a promising album tank so quickly—and what caused it to eventually bounce back? Some speculate that a faulty marketing strategy sank Dusty in Memphis—that in promoting the album, Atlantic Records had tried to obscure the influence of African American music on Springfield’s sound. “Given the hateful racial climate of 1968 and the worsening polarization of 1969, it is not surprising that Dusty in Memphis was a commercial failure,” writes Annie Randall in her 2008 book, Dusty! Queen of the Mostmods. Downplaying the impact of singers like Franklin and Mavis Staples—Springfield’s idols—only hurt the smoky-voiced singer. “The fact that ‘Son of a Preacher Man’ was the album’s first and only hit,” Randall continues, “suggests that Atlantic’s marketing strategy to distance Dusty from soul backfired.”

The lackluster sales stalled Springfield’s career, and her next release in 1970, A Brand New Me, hardly rebounded. Subsequent releases failed to find much footing. Though Memphis sold poorly, it did find its way into the hands of a small but influential following. The Pet Shop Boys, stars themselves who were longtime fans of Springfield’s work, collaborated with Springfield for “What Have I Done to Deserve This?” in 1987. And in 1994, Quentin Tarantino tapped “Son of a Preacher Man” to soundtrack an iconic moment in his cult classic, Pulp Fiction—he’s said he would have cut the scene entirely if he hadn’t gotten the rights to Springfield’s recording.

Springfield’s peers in the recording industry helped amplify her influence, too. “Son of a Preacher Man” has gotten the cover treatment from Mavis Staples, Bobbie Gentry, Tina Turner, Dolly Parton, and yes, the Queen of Soul—only after hearing Springfield’s version did Franklin decide that maybe the song did fit, and released her version in 1970. “Preacher Man” wasn’t Springfield’s only contribution to strike a chord in the music community, either—in 2008, Alabama-raised singer Shelby Lynne released an entire album of Springfield covers, including Memphis tracks like “Just a Little Lovin’” and “I Don’t Want to Hear It Anymore.”

“Dusty Springfield’s singing on this album is among the very best ever put on record by anyone,” wrote musician Elvis Costello, who contributed the liner notes on Memphis’s 2002 re-issue. “It is true to say that the voice is recorded in the audio equivalent of ‘extreme close-up.’ Every breath and sigh is caught and yet it can soar.”

And soar it has—Rolling Stone and NME both designated Dusty in Memphis as one of the 100 greatest albums of all time, and its slow-burning Memphis-grown sound went on to inspire blockbuster talents like Adele and Tom Petty. “The fact that this record has had such a fantastic afterlife,” Springfield is heard saying in the 2006 BBC documentary Dusty in Memphis, “has been one of the joys of my life.” Springfield died of breast cancer in 1999, eleven days shy of her induction into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. But her sound—and the Southern forces that molded it—paved the way for countless artists to come.