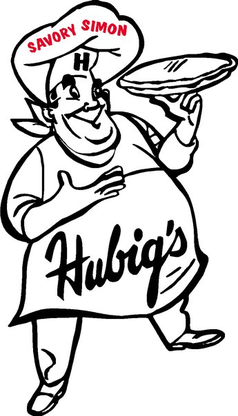

In the Marigny of New Orleans, on my friend Miriam’s kitchen wall, hangs a picture frame containing one crinkled white wax-paper wrapper. The fat chef we call “Savory Simon” stands staunch in the center of it, twirling a pie on the tips of his fingers, his toque a mushroom cloud the color of lemon curd. The word Hubig’s scrawls across his belly, over what was once the belly of the hand pie sealed inside.

C. Morgan Babst

Seven years ago, Miriam opened that wrapper and bit through the sugar-slicked thick fried crust into the jammy peach middle—the last Hubig’s pie she expected ever to eat.

That morning—Friday, July 27, 2012—a fire had broken out in the fry room at the Hubig’s Pies factory on Dauphine Street. Since 1921, when Fort Worth baker Simon Hubig opened a chain of shops across the South, the sweet aromas of pie had emanated from that white brick building. Now, it just smelled like smoke. As the fire-fighters battled the five-alarm blaze, legend has it, they began to cry. Though the New Orleans factory had been the only of Hubig’s plants to survive the Depression, even the tears of the firemen couldn’t save it now. The factory burned to the ground.

As news of the fire spread across the city, people dashed into drugstores, hardware stores, gas stations, and grocery stores and stocked up on Hubig’s pies. My dad snagged two, which he doled out in small slices for days. Over the coming years, plans to rebuild the factory would fail to yield fruit, and, until last Thursday, we believed that these pies—stocked in freezers or long since scarfed down—were the last we’d ever eat.

Courtesy of Hubig’s

Before that fire, Hubig’s pies were a daily pleasure in New Orleans, like king cake during Carnival or snowballs in summer. As a girl, I’d get a lemon pie from Harry’s Hardware when I helped my grandmother run errands. As a boy, my husband would buy an apple pie from the deli after school. On days when he felt rich—when he had a quarter, say, and not a dime—my dad would get a Hubig’s to go with his can of red drink after baseball. Miriam’s friend Susan would eat them on the Algiers ferry, as she watched the river churn.

A 1922 ad for Hubig’s Pies.

Those fried pies, cheap and cheerful, were a staple—the kind of thing New Orleanians carry with us when we travel. (I tote Steen’s syrup around the country, and my dad brings Luzianne coffee. Miriam packs Zapp’s. Susan carries Bunny Bread and cans of Dubon peas.) Without Hubig’s, the world just tasted wrong.

Then, last Thursday, the Louisiana governor’s office issued a press release: our hand pies were coming back. Hubig’s owner Andrew Ramsey secured a loan, and plans to build a bakery in Jefferson Parish are afoot. It’s not a lot, but it doesn’t take much to get our hopes up. New Orleans is overjoyed.

Few things make New Orleanians happier than zombie pastries. Around Mardi Gras, my feeds fill with haloed photos of king cakes from McKenzie’s—a bakery dead now for nineteen years. McKenzie’s closed its shops in 2000, but then its donuts, jelly rolls, cinnamon buns, and brownies returned. Their recipes were bought by Tastee, who executes them faithfully and even slaps a green McKenzie’s logo on the bag. I’m partial to the donuts—buttermilk drops to be precise—but whenever I buy a dozen, I’m sure to leave them out on the counter for a day until they develop that signature McKenzie’s staleness that makes them taste just right.

“Rightness” is essential when you’re resurrecting dead desserts. One misstep—bake a hand pie that should be fried, swap butter for shortening, sprinkle cinnamon sugar on the crust—and the memory collapses in a puff of sugar, leaving nothing but a sweet ghost hanging in the air. No one yet has been able to recreate a Hubig’s pie, though imitations abound. Even the homemade pies that try hardest, waiting in their white paper wrappers by the register at the dry cleaner, don’t quite hit the spot. No one I know has tried such stand-in hand pies more than once.

“Either the crust is too thick—” my dad tells me.

“—or it’s the wrong kind of filling.” My husband finishes this thought.

“Something about it,” says Susan, “just isn’t right.”

“We won’t change a thing,” Hubig’s Andrew Ramsey reassures us in the morning paper—in New Orleans, this counts as news.

Still, some of us fret about this promised new factory with its shiny pots and new machines. Without ninety years of grease to season those conveyor belts, can our pies really come out right?

We may be getting ahead of ourselves in our excitement: planning pie parties and refreshing our Hubig’s Halloween costumes, designing pie-themed floats in advance of next year’s Mardi Gras. Even if all goes well, we still have at least a year to wait until the new factory turns out pies.

My cousin Alice, who grew up with a Hubig’s heiress—her wedding shower featured Hubig’s pies custom-stamped with her and her husband’s names—called her as soon as she’d heard the news. “You’d better not be toying with our emotions,” Alice warned her.

It’s true we’re feeling some feelings—a kind of advance sugar high.

Courtesy of Hubig’s