In 1935, at a literary conference in Baton Rouge, folklorist and scholar Benjamin Botkin looked out at an audience that included Robert Penn Warren and Randall Jarrell and declared that Southern poetry, as a distinct category, didn’t exist. “One of the things that strikes the outsider about Southern writing,” said Botkin, a native Bostonian living in Oklahoma, “is that as soon as one stops writing prose and becomes a poet, one ceases to be a Southerner and even poetic.” Rebuttals, if they came, were muted: grumbles here and there, maybe, handkerchiefs dabbing sweaty necks. Six decades later, in an essay, the Virginia poet Dave Smith tried wrestling with Botkin’s assessment but fell short of a pin. Was there anything to distinguish the Southern poet, Smith asked, from an American poet from any other region? His puckish answer: “Yes, no, and maybe.”

A trio of new poetry collections would seem to point that needle toward yes. At a surface level, what unites these books is the happenstance timing of their publication and the geographic coordinates of their authors’ births. But then at times, flickeringly, emerges something else: a humid intensity, a magnetic orientation toward home, and an emotional dissonance that together expose a Southern taproot even Botkin couldn’t deny.

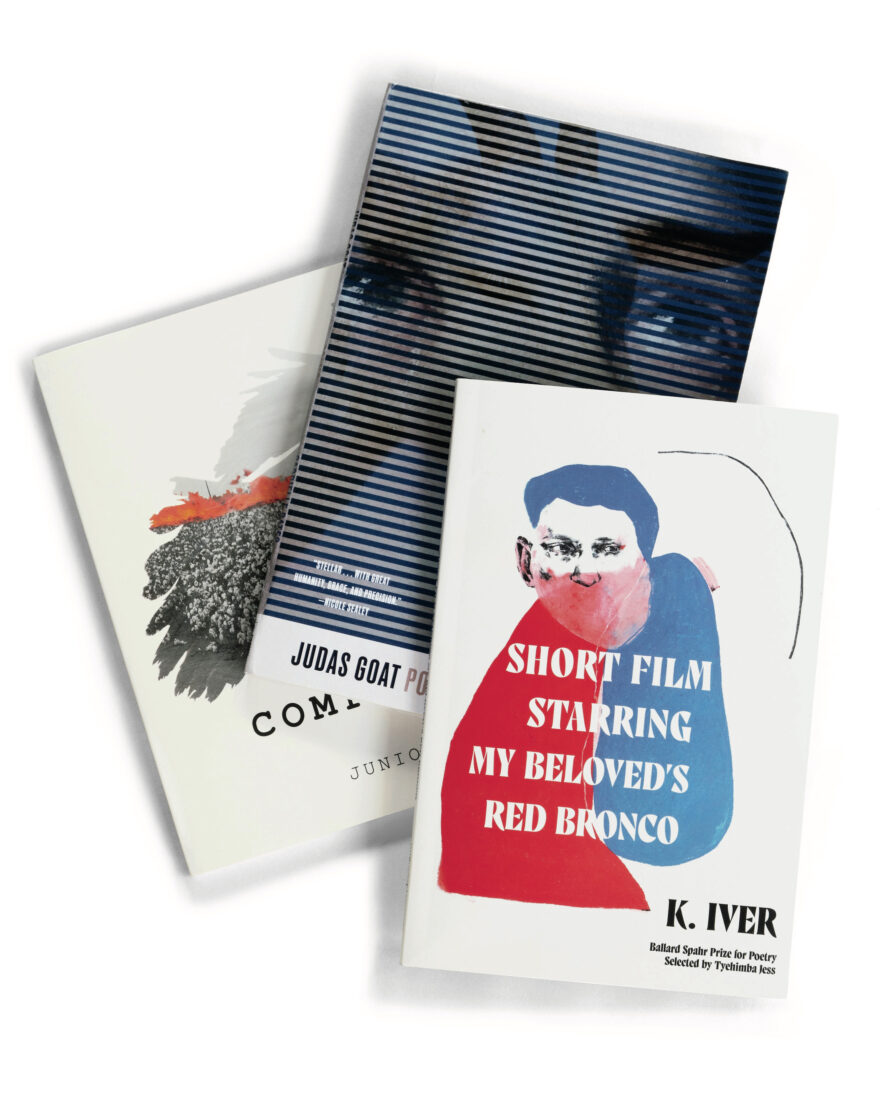

In the forty poems in Judas Goat, Gabrielle Bates’s ravishing debut, sacred and unsacred longings find their embodiments in cemeteries, barnyard animals, squirrel and snake carcasses, mudbanks, and ghosts from scripture. In “Dear Birmingham,” a nod to her birthplace, Bates writes: “I was once so terrified of my own contentment / I bit my shoulder / and drew blood there.” Bates’s writing is anything but bloodless: Legs are shaved “amphibian-smooth,” mushrooms wear soil “like Catholics bearing ash,” ferns fiddle from “an old magnolia’s many armpits.” These are not, however, poems for the squeamish. A dog suffers a horrific death in one. A piglet meets a grisly fate in another, “four black hooves like split rocks scattered on the porch.” The caveat here is that neither is life for the squeamish. Bates apprehends this, and refuses to flinch, or cease longing.

Composition, another debut, comes from Junious “Jay” Ward, a poetry slam champ and the inaugural poet laureate of Charlotte, North Carolina. More a collage than a collection, the book takes a kind of depth sounding of Ward’s identity: biracial, male, Southern, Baptist, raised in a town “small like an atom you need to stay and escape / from, split without exploding.” But the personal, for Ward, is also the political; hence his righteous disemboweling of Virginia’s Racial Integrity Act of 1924, a law criminalizing his very existence. Ward, thrillingly, heaps everything into Composition: visual poetry, an imagined conversation between Ma Rainey and Elvis Presley, etymologies, redacted documents, an ekphrastic ode to TV’s Black-ish, family and historical photos, Dick Gregory quotes, footnotes, drawings, news clippings, and lyrical poems shot through with pathos, with unexpected nostalgia, with raised fists, with an exquisite kind of blues.

“I’m trying to / unwrite this place.” That’s K. Iver, the author of Short Film Starring My Beloved’s Red Bronco, and the place—psychic bruise as much as a location—is Iver’s native Mississippi. Short Film’s thirty-one poems orbit the teenage love affair between Iver—who is nonbinary trans—and Missy, a “blond boy forced to call himself a girl.” Memories of swapping candy outside homeroom, of yearbook photos, of “the decade-old landline that held our breaths until 3 a.m.” get subsumed in a torrent of heartbreak: In 2007, at twenty-seven, Missy committed suicide, a harrowingly common fate for trans youth. Short Film is one of the most powerful excavations of grief in recent memory, a genderqueer kaddish that veers from guilt (“I have a body / and you don’t”) to despair to tenderness to searing anger (at Iver’s mother, who separated them; at the small-minded townsfolk who wished them consigned to hell’s flames). Iver’s poems will turn you inside out. “You held many more objects,” goes one,

than a chair and a rope. Faces

have softened in your hands.

Steering wheels have lived

there a long time. But I can’t

celebrate that. Not yet.

I can’t praise the smooth

contours of your nose

without wishing it were still

a nose. Without asking Mississippi where it was

that night.