I stepped out of the cold and into Doc Watson’s living room. It was a sunny day in the Blue Ridge Mountains, and there was still snow on the ground from a recent storm. I was thirteen years old—a kid with braces, skate shoes, and a limited appreciation of music. I knew of this legendary North Carolina folksinger and guitarist, who had played for presidents and won every award they give for making music. I had even begun learning one of his songs from my guitar teacher, but up until that point, my musical interests seldom reached beyond the artistic ventures of Kurt Cobain or Jimmy Page. So how did a kid still relatively oblivious to the history of American roots music find himself in the home of one of its most celebrated masters?

Wayne Hayes was a man who lived in my hometown of Concord, North Carolina. He was a local guy, a music lover, a song- writer, and a social studies teacher at the high school I would eventually attend. Around 1988, he wrote a song in honor of Doc’s famed son, Merle, who had recently passed away. He sent the song to Doc, a gesture that would prove to be the beginning of an enduring friendship. Wayne was also a friend of my father’s (it seems that in a small town, guys who play guitars and sing old country songs are bound to become friends sooner or later). They got together often in my dad’s wood shop or in whatever garage was available to talk, play songs, tell stories, and maybe have a cold beer.

Around 1993, Wayne asked my father if he’d like to visit Doc at his home in Deep Gap, North Carolina. Thankfully, Dad passed the invitation on to me. He figured this extraordinary opportunity would be more valuable for a young person, especially one with a few years of guitar lessons under his belt (or maybe he just saw an obvious advantage in the possibility of hearing something other than Nirvana’s Bleach blasting from the speakers in my bedroom). Doc was scheduled to play in Winston-Salem in a few weeks, and Wayne set it up for me to meet him during the day at his home, and to go to the performance with them that night.

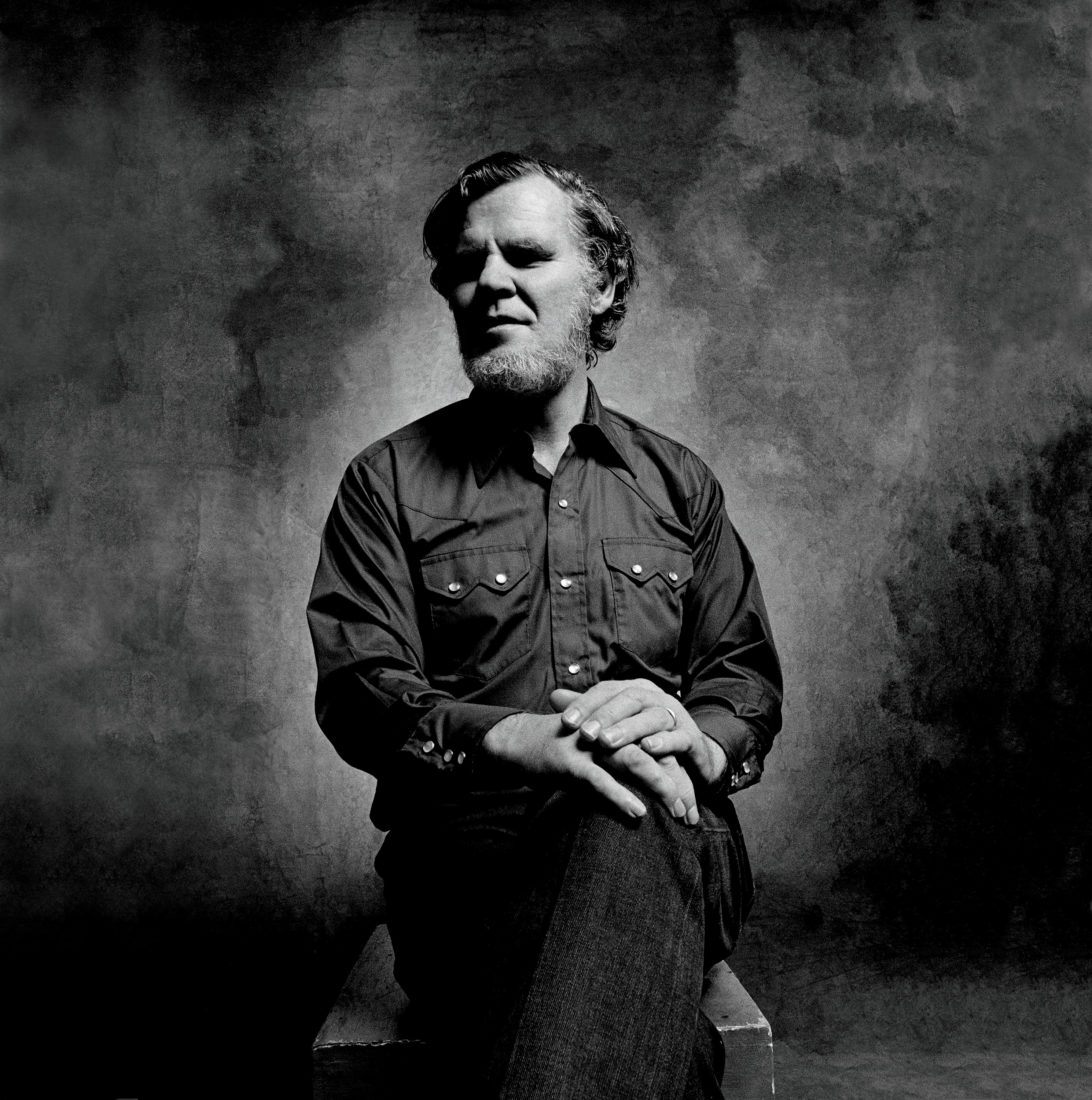

Photo: Tim Mosenfelder/Getty Images

Timeless Voice

Watson during a 2005 performance.

One of my only associations with Doc Watson was the quiet and beautiful black-and-white photograph on the cover of the Memories LP. It was a record that had been on a shelf in our living room since before I had any memories of my own. When I was a young child, that image, with all its wisdom and reverence, made him interchangeable in my mind with Abraham Lincoln.

At the time of this writing, I am thirty-one years old. I remember the experience of going to Doc Watson’s house in the same way one might remember a first day at a new school, or a first breakup, or the first time driving a car with no one else in it: an event when you know things will not be the same after this. My mind was about to be opened musically, and by someone esteemed and respected the world over, no less.

The nature of the visit and the surroundings were in no way glamorous. He appeared to live the relatively simple rural life that one might expect from his music. He lived in a modest home in a beautiful part of the state, in a friendly and uncrowded neighborhood near the Blue Ridge Parkway. We sat in his living room and talked about music. I remember Rosa Lee, his wife of forty-six years at the time, making something in the kitchen. She talked with me about their garden, about which vegetables had done well that year and which hadn’t. His daughter, Nancy, showed me around the house; I saw a hammer dulcimer for the first time, sitting in a small room that also happened to have six or seven Grammys on one wooden shelf. They had a couple of cats. I remember that when Doc opened the door by the carport, he somehow knew if they were there, despite his blindness. It was incredible. I recall thinking his hearing must be very different and clearly more advanced than mine. He let me play his guitar, and I showed him what little I had learned so far. He gave me some pointers. He gave me a pick. I remember feeling very calm, very at ease sitting and talking with him. So much of his character was right there, at the forefront of casual interaction: humility, knowledge, care, humor.

The performance that evening was at Salem College. Doc would be playing solo, and Wayne drove the three of us to the venue. We stopped and had supper at a K&W Cafeteria. I remember a swell of pride as Doc asked me to guide him into the restaurant. We walked slowly through the cafeteria line, his hand on my shoulder. I was nervous because I thought I might mess up somehow.

When we arrived at the college, I helped carry his guitar and amplifier inside. During the show, he played the song I was trying to learn at the time and, much to my amazement, mentioned me in his introduction—something about how there’s a young fellow in the audience trying to learn this one and that he’s doing a good job with it. I remember how clear his voice was, and how melodic his picking was, and how I, along with the rest of the audience, was completely rapt. I had never experienced a performance like it: simple in presentation, technically complex at times, highly professional, engaging, relatable, and vastly entertaining. He was funny and friendly and human and powerful but not in a way that I had ever seen before. In my mind at the time, “power” in musical performance was often synonymous with “volume” or even “aggression.” The power Doc had as a musician, and as a person, was not of the variety that required loudness. On the stage his ability to tell a story and to interpret a song so fully and with such a natural feel for melody was enough to draw the undivided attention of everyone in the room, no matter the size. Millions would have this experience firsthand throughout his eighty-nine years. His was a voice of unparalleled temperament, even and strong, graceful yet gloriously matter-of-fact. It truly was, and will remain, one of our classic American voices, rightfully in the company of Louis Armstrong, Hank Williams, Sr., Elvis Presley, Ella Fitzgerald.

In life, Doc was friendly and respectful to strangers, friends, family members, and fans. He exemplified patience, and brought joy and laughter to those with whom he came in contact. In conversation, he spoke and listened with interest, even to a thirteen-year-old kid from Concord.

When the show was over that night, I sold merchandise for Doc Watson. It took so much concentration just to count the change, as I was buzzing so intensely from the performance I had just witnessed. My dad was there for the show, and as people made their way out of the venue, we walked over and said our good-byes to Doc and Wayne. My dad thanked Doc for allowing me to come and visit, and Doc told him it was a pleasure to have me along and that I helped a lot. His saying that remains one of the proudest moments in my memory.

Doc Watson changed the way I saw the acoustic guitar. He changed my understanding of how a song could be presented in sound and mood. He made me laugh, and he made me listen more intently to the melody. He helped lead me to a uniquely rich tradition of music, and to a path of research and inspiration that continues for me daily. I am eternally grateful to this man who spent so much of his life sharing songs, and who was kind enough to share some with me all those years ago, on a clear day in the Blue Ridge Mountains.

Timothy Seth Avett is a founding member, with his brother Scott, of the Avett Brothers.