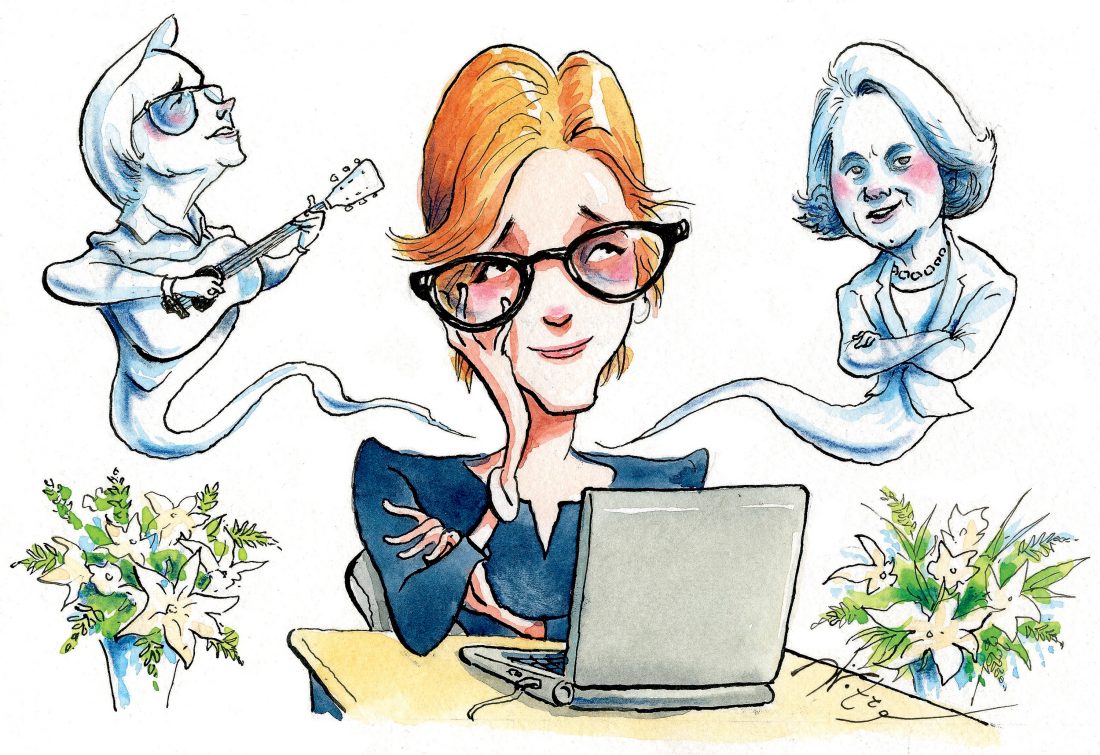

During the past year, almost four months to the day apart, two people who had a profound influence on my life died: Jean Harris, eighty-nine, my headmistress at Virginia’s Madeira School who was referred to derisively as Integrity Jean; and George Jones, eighty-one, who was, well, George Jones and referred to good-naturedly as No-Show Jones and the Possum. Jones’s song “He Stopped Loving Her Today” is arguably the best country music recording ever made, and the sausage sold under his name was so good I wrote a New York Times column about it. (The inclusion of a recipe for sausage balls, a Deep South cocktail party stalwart Jones had never heard of, prompted the following outbursts from the man himself: “I’ve got the sausage and I’ve got the balls—ha!” and, “Say Mama, they’re burning up my sausage…. Don’t worry about your sausage, son, you better worry about your balls”). But despite the countless hours of entertainment (both musical and comical) I’ve derived from Jones, Harris’s influence was rather more dramatic: Had she not murdered Herman Tarnower, her longtime lover and author of the wildly successful The Complete Scarsdale Medical Diet, I might not have had a career.

This, in a—sort of—nutshell, is what happened: During my junior year at Madeira, the almost entirely all-male board decided with typical wisdom to replace our brilliant but decidedly masculine headmistress (who went on to become town supervisor of Shelter Island, New York) with Jean Harris, even though her most recent job had been manager of sales at a Manhattan-based company that sold cleaning contracts to office buildings, and when I later interviewed a former board member at a previous school where she’d been head, he blamed her for its ultimate demise. When she was introduced on the hockey field during the spring Fathers’ Weekend (in a bow to the number of divorced parents, the traditional Parents’ Weekend had been split in two), I took one look at her, turned to my father, and said, “One day they are going to come get that woman in a truck.”

My father, like most of the rest of the assembled dads, had already pronounced her “attractive” in her knockoff Chanel suit, and mumbled something about my dislike of authority (which is not exactly true—I just prefer it when the people nominally in charge of my well-being possess some modicum of sanity). At any rate, the following year proved my instincts right. She walked through campus head down, yanking at her hair; once, at a “relaxed” meeting at her house, she sat with us on the floor and pulled up huge clumps of carpet. We had no way of knowing that she was taking the methamphetamine Desoxyn (along with Valium, Percodan, Nembutal, and other goodies revealed to have been in her medicine cabinet), or that she was in the grips of an increasingly desperate obsession with the famous Dr. Tarnower.

Whereas her predecessor didn’t much care what we did as long as we worked our asses off academically, Harris clearly had more literal goals in that department. She put the entire school on what turned out to be the Scarsdale Diet, she hammered incessantly at our general lack of ladylikeness, and twice in her yearbook letter to our graduating class, she underlined the importance of a “stout heart.” No wonder—in a scenario familiar to country music fans everywhere, it turns out that she was being eclipsed in Tarnower’s affections by his younger, blonder office assistant, a woman whom the high-minded Harris derided in a letter to her lover as “tasteless,” “ignorant,” “cutesie,” and, for good measure, “a slut.” It was the latter’s frilly negligee and pink curlers that Harris spotted in Tarnower’s bathroom on that night in 1980 when she pumped three bullets into his chest from several feet away, an occurrence she forever termed a “tragic accident.”

By then I was a sophomore at Georgetown and a part-time library assistant/phone answerer at Newsweek’s Washington bureau, a job I’d gotten via Madeira’s ingenious cocurriculum program, in which the students are bused off to D.C.-area internships once a week. On the morning after Harris shot Tarnower, the bureau chief woke me up with an order to get out to my old school. When I asked him why on earth, he barked, “You idiot, your headmistress just shot the diet doctor.”

Looking back, I realize I had none of the usual reactions. Instead, I threw on clothes, jumped in the car, made my way past the guards (with whom I’d made sure to be on extraordinarily good terms during my slightly shady school tenure), and got the scoop on all that had transpired before Harris drove off campus armed with a gun. On the way back, I stopped at a pay phone to make an especially fulfilling “I told you so” call to my father (even the truck part was right—deliciously, Harris had been transported from the crime scene in an old-fashioned paddy wagon). Then I typed up my notes, filed my story to New York, and got my first-ever byline. I was nineteen and only the tiniest bit sorry that the good doctor had given his life in service to my future as a journalist.

It has been during that career that I’ve had the privilege of meeting many a country music great, including Jones, largely through my friend Susan Nadler, to whom Jones referred to with affection as “my little Jew” and who was also part owner of his record company. Susan has worked with everyone from Willie Nelson and Kris Kristofferson to Tammy Wynette (Jones’s third wife and singing partner) and is herself no stranger to crime. She once did time in a Mexican jail, an experience immortalized in a memoir called The Butterfly Convention, and she wrote another fine book, Good Girls Gone Bad, in which Harris could easily have been a chapter. Anyway, just before Jones died, he sent Susan a letter promising her a spot next to Johnny Paycheck in his private group of cemetery plots, and while we were cracking up over that, um, generous offer, among other evidence of Jones’s decidedly off-kilter but weirdly sweet nature, it occurred to me that Jean and George had more in common than might initially be apparent.

Harris was born in an affluent suburb of Cleveland, Ohio, while Jones was born in an area outside of Beaumont, Texas, known as the Big Thicket. Harris went to Smith College and graduated magna cum laude; Jones went to Jasper, Texas, where he played and sang on KTXJ radio. Which is why it is always instructive to go deeper. For one thing, the emotional use of a firearm landed them both in a lot of trouble. Jones shot up an untold amount of hotel rooms, some houses, the floor of one of his tour buses, and the car of his good buddy Peanut Montgomery, for which he got slapped with an attempted murder charge that was later dropped. And while the only room we know for sure Harris shot up was her boyfriend’s Scarsdale bedroom, it turned out to be enough, since it landed her in a women’s prison for twelve years.

Then, of course, there was the fondness for drugs (Jones preferred cocaine and whiskey over Harris’s pills) and the resulting paranoia. Jones was variously convinced that monsters were crawling in his car or that he’d been targeted by the mob, and he was once carted off in a straitjacket. For her part, Harris accused her rival of subjecting her to all sorts of indignities, including cutting up her clothes—though Harris herself had cut up a needlepoint rug made by yet another woman whom the doc had earlier dated, and mailed the pieces back to her in a shoebox. When it came to tortuous love affairs, Jones, not surprisingly, took a more direct approach—on the night he took Tammy away from her then husband, he simply turned over a dining room table and shot the lamp.

It was always said of Jones that he was such an astonishingly moving interpreter of country songs because he’d lived most of their content, but plenty of Jones’s titles (if not the exact lyrics) could have been applied to Harris’s tawdry saga. “She Thinks I Still Care,” “Why Baby Why,” and, of course, “He Stopped Loving Her Today” come immediately to mind.

Harris wrote that she found redemption (even though she never actually admitted guilt—she was, she said instead, an “instrument” in Tarnower’s death) by campaigning for a nursery for the children of fellow inmates. That’s nice, but I’ll take Jones’s 100-plus albums and unmistakable voice filled with that aching vulnerability and full-on heart—qualities the jury could never locate in Harris, who wore fur-collared coats and an air of superiority to court every day.

With heart also comes humor, and the all-important ability to laugh at oneself. During our first interview, I had to confess to Jones that I’d run over one of the newly installed lights in his driveway. “That’s okay,” he shot back, “I’m partial to guardrails myself.” It was a hilarious afternoon (before he even agreed to return home from his daily lunch at Subway, he had to be reassured I wasn’t a Yankee), punctuated by the Jones magic. At one point he broke into a spine-tingling a cappella version of Don Gibson’s “I Can’t Stop Loving You.” It’s not a bad epitaph for both Harris and Jones—for the former, one leaning toward the bitterly ironic, and for the latter, entirely fitting. Those close to Jones say he never completely let go of the torch he carried for Wynette, and he certainly held on to his deep love for “true” country and his sainted fourth wife, Nancy, who is credited with keeping him—mostly—straight, and who will be buried beside him.

Want more Julia Reed? Her book South Toward Home is a collection of both rollicking and warm stories about the highs and lows of Southern life.