Home & Garden

Back to the Land

Three young women return to their roots––and the family farm––and in the process find that the old ways are sometimes still the best ways

Photo: Squire Fox

Jennifer Niceley will never forget the day she and her sister Anna taught themselves how to butcher broilers from a YouTube video.

“It was three years ago,” says the thirty-nine-year-old singer, her voice a slow syrup of a drawl. “My mother and grandmother knew how to do it, but I’d never been taught.” Nonetheless, it was harvesttime, and there were 150 chickens and three days to process them. So Jennifer and Anna streamed, learned, and got busy. It wasn’t exactly Slaughtering for Dummies, but it was close.

“I wasn’t a good executioner,” Anna, who is thirty-six, confesses, sitting at her sister’s kitchen table early on a recent morning, a basket of three dozen just-gathered eggs at her feet. “I was good at plucking the feathers. Peeling the feet. Making stock from the carcasses.”

“We butchered the birds humanely,” Jennifer stresses. “But it was still emotional. That moment is hard. That’s why every culture has rituals around hunting and killing. So it never gets nonchalant.”

The Niceley sisters, along with their friend Misty Travis Oaks, who is thirty-nine and whom they consider “close as family,” run their restaurant and event business from their home base of the Niceley farm in Tennessee, a place all three women were intimately connected with growing up.

“Jennifer and Anna were born and raised at Riverplains,” Misty explains of the centuries-old homestead. “And my father and uncles worked on the family land as day laborers back in the early sixties.” The young men were paid with watermelons and tickets to the drive-in theater, which the Niceley family also owned at the time. “They hardly cared,” Misty says with a laugh. “They just loved being on the farm.”

Originally a commercial dairy, Riverplains is one of those astonishing places so rich with beauty, simply laying eyes on it makes you feel a little drunk (and willing to work for watermelon). Located a thirty-minute drive east of Knoxville, the Niceley property is part of Strawberry Plains—population around 4,500, and so named because in the 1800s wild strawberries grew plentifully enough in the fields that they stained the fetlocks of passing horses red with juice.

Riverplains has been owned and inhabited by the Niceley family for generations, four of which still reside there. The farm covers more than four hundred rolling acres, which hug both banks of the Holston River, and has remained so unaltered over the ages that the narrows still hold a primitive fish trap one visiting archaeologist dated back to before the 1500s. The trap is a simple stack of rocks that could have been easily moved at any point, and yet, there it sits as if frozen in some sort of Southern amber, a literal touchstone offering hope that no matter how messed up modern life becomes, there will always be pockets of the past we cannot destroy.

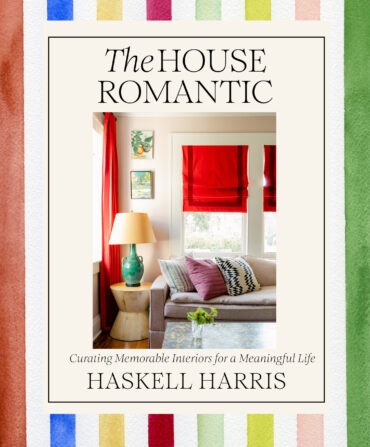

Photo: Squire Fox

This comforting timelessness is, as much as anything, why the Niceley daughters chose to return from

their wide-flung urban wanderings to settle and farm Riverplains, enlisting Misty as their partner in progressive agriculture. The three of them joined forces nearly four years ago to run an old-fashioned, one-stop, Southern food operation that includes select wholesale—local chefs snap up cornmeal, grits, eggs, raw milk shares, grass-fed beef, and pastured pork—a non-GMO food truck, cooking and butchering lessons focusing on historic methods of grain, meat, and dairy prep, and soon, a brick-and-mortar Knoxville restaurant called Mister Canteen. The trio tends every crop from soil to plate—call it seed to table—a food initiative they believe bridges the gap between farmer and chef.

“I love being able to bring our food to people in every form,” says Anna, a certified holistic nutritionist. “We are farming it, harvesting it, preparing it, and serving it.”

Originally intending to become a lobbyist, Anna spent her twenties working on various campaigns after graduating from American University in Washington, D.C. Her fascination with politics came from observing her father, Frank Niceley, a lifelong farmer and elected official who currently serves as a Republican state senator in Tennessee.

“I moved to New York City, which was amazing,” Anna recalls. Then, after bouncing around the country, trying to find a job she enjoyed and a place she could call home, she met her future husband, Dino. “We knew we wanted to marry and have children. And then, Dino got sick.”

He lost twenty-five pounds in six days. The eventual diagnosis was colitis. The scare instantly reprioritized their lives and reignited Anna’s curiosity about diet as medicine, something her family had ingrained in her and her sisters as children.

“I read The Maker’s Diet, dug into Michael Pollan’s books. We’d grown up with a practice of home cooking, everything being made from scratch from our farm. We never had anything out of a box, only fresh food.”

After Dino’s illness, Anna thought, too, about how robust her parents seemed to be compared with other adults their age, something she attributed to their lifestyle and diet.

“My father always says he eats ‘the way his daddy did,’ and Granddad lived to be ninety-four and never used a cane,” she says. “At sixty-seven, our father is so hale and hearty. He doesn’t take any medicine. He doesn’t need a doctor all the time. Dino’s dad has this whole bag devoted exclusively to his pills: blood pressure, heart stuff, cholesterol. My folks don’t have any of those issues.”

Photo: Squire Fox

The path seemed clear. “It just dawned on me one day, instead of casting about for a healthy place to raise our family, why don’t we just go back to the farm?” Anna recalls, widening her eyes, the epiphany still a bit surprising even now, years later. As a girl, she had been so eager to leave, certain the city would bring her the type of stimulation and challenge she craved. “But after years of roaming around, wondering why nothing fit, I figured out I’m not supposed to be anywhere else.”

The week they settled at Riverplains, Dino started driving the tractor. This was beyond a reach for her husband, as he didn’t even own a car. Misty chuckles at the memory of looking out onto the pastures and seeing “this totally tattooed hipster guy in the middle of these Jersey cows.

“It was a crash course for all of us,” Anna recalls. “That same week my mom announced, ‘I’m going out of town, so you need to milk the cows.’ And I was like, ‘Ohhh. Oh-kay.’”

Jennifer’s path back home was even more unexpected. After spending a few years in Wales, she settled in Nashville to become a musician, doing “whatever I could to survive so I could make records.” She had a spot of success, but the industry wore her down, as did a series of failed relationships. Missing the straightforward pleasures of the land, she moved to North Carolina with another man, this time to try her hand at primitive mountain living, outhouse and all. “I wanted to go back to basics, learn to be more self-sufficient,” she explains.

When that partnership also soured, Jennifer rang Anna, who drove to the mountains, picked her sister up, and escorted her home to Riverplains. With winter around the corner, Jennifer decided, against her instincts, to stay put.

“I couldn’t see myself fitting in here again,” she says. “But, given all that had transpired, I thought, I’m just going to sit still for a second and see what happens. I was disappointed that what I’d labored so hard for hadn’t turned out the way I’d wanted. I was in my early thirties looking at myself, kind of like, now what?” But farm chores wait for no existential crisis, and Jennifer found the call to tend to the animals a welcome break from hobbling introspection.

“It felt really good to be doing things with my hands,” she says. “To be outdoors. I remember walking back with the milk pail at night, and thinking, Oh my God, I’m so glad I’m here and not in some club in East Nashville. I felt connected to something real.”

She taught herself how to make cheese, butter. How to raise chickens, goats, pigs, and cows. “It was the self-education in all the homesteading arts that I had been dreaming about.” She also planted open-pollinated Hickory Cane, an “old-timer’s corn”—a low-yield, photogenic crop that the Cherokees had grown when they farmed what became Riverplains.

Her father, Frank, wasn’t sure about the choice. “Most farmers don’t fool with it,” Jen-nifer explains of his logic, but once the lovely stalks sprang from the ground, suitors came calling. “There was immediate interest, because no one else was growing organic, nonmodified corn. You can’t get it.”

Riverplains is now contracting with an artisanal distillery, Knox Whiskey Works, to make organic, non-GMO whiskey, one of the only ones available on the market.

“That was a big victory for me,” Jennifer says, with a relieved grin. “It showed my dad I wasn’t crazy. And that this farm can do the responsible thing and still bring in money.”

As Jennifer and Anna made their personal transitions, so too did the farm. Out went the chemical fertilizers. And the GMO crop leases that had been held on the fertile bottomlands. Ruminants were permitted to graze freely. All the animals started feeding on non-GMO grains. Every cow and goat was milked by hand.

The shift required a number of heart-to-heart chats with their father, a staunch conservative who focuses on the bottom line. “I explained that our land had been abused for decades,” Jennifer says. “And we needed to rescue it. For him, a lot of changes I would suggest were actually things they used to do before the seventies. He’d say, ‘Well, that’s how Daddy used to do it.’ We were able to get on the same page that way.”

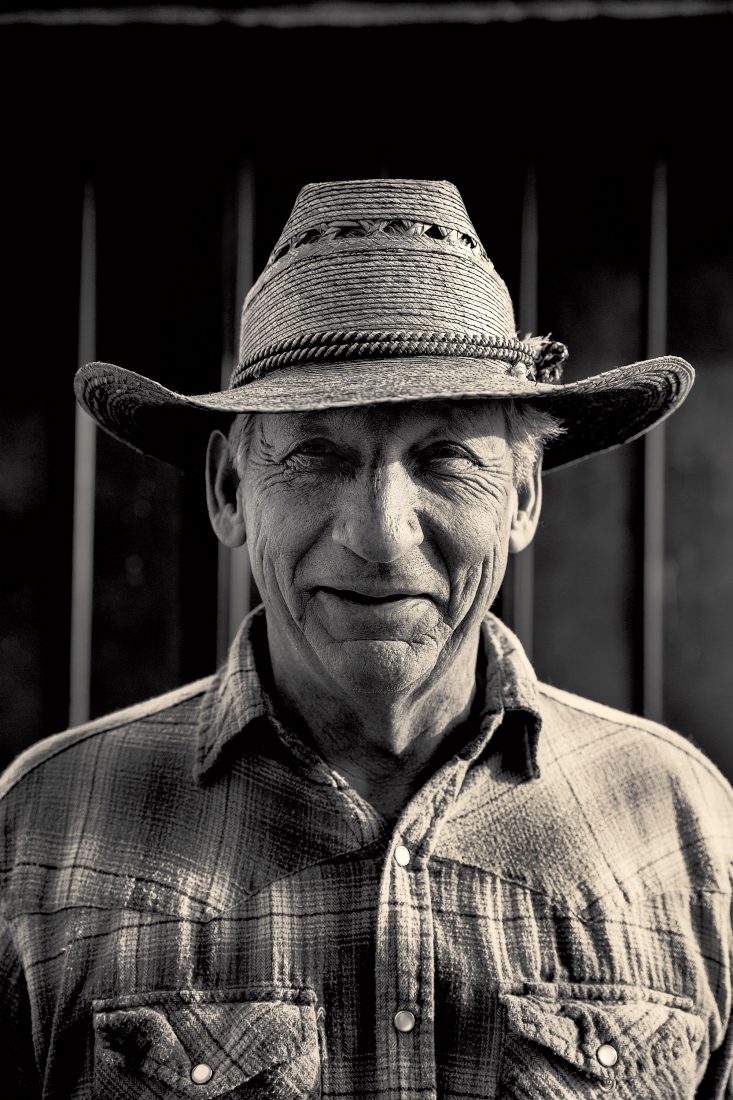

For the senior Niceley, the journey from shrugging acceptance of Big Agra to becoming an heirloom preservationist has been swift and enlightening. “I can see now that it’s not really true you can’t feed the world without genetic modification,” he says. “It’s more work, but it’s worth it in the long run.”

Spending his whole life on the farm, Frank Niceley observed the connection between time-honored methods and longevity. “You have to have healthy soil for healthy plants. Healthy plants mean healthy crops and animals.” More to the point: “Feeding dairy cows, you apprehend the value of nutrition. One little thing can be off, and they go down.”

Last year, Senator Niceley introduced a bill requiring seeds and plants sold in Tennessee to be labeled to indicate open pollination, genetic modification, and hybridization, and in May of this year, he pushed to have industrial hemp made legal to farm again in the state—both issues typically regarded as left-leaning causes. Niceley insists he’s still the same conservative he’s always been.

“All I’m saying is we need to be farming the way our grandfathers did,” he explains. “The old ways are the best ways.”

Photo: Squire Fox

There is still a traditional farm lunch served at Riverplains every afternoon. The weathered wooden table sags under the weight of bowls of beans, platters of cornbread, cottage cheese, pickles, and eggs. Anna and Dino’s girls, two-year-old Maggie and five-year-old Montalee (named after their great-grandmothers), come eat after their farm chores. So do all the uncles, cousins, and grandparents still active on the farm.

“We have fifteen relatives who are here every day,” Anna says. “It’s our own sweet community.” She acknowledges, “It’s not always easy to live with parents and siblings as adults, but the pros outweigh the cons. Having all that history around. The wisdom from their ancestors getting passed along to the kids.”

“Thankfully,” her father chimes in with a chuckle, “it’s a big place.”

Over the past decade, there has been a statistical uptick in family and micro-farms. “I’ve noticed more and more young people asking me questions about farming,” Frank attests. “It’s in our DNA. People have a thirst to raise something.”

There may be another reason the back-to-the-land movement is growing: No one feels shitty on a farm.

“Every time I come here, I think, This is how you should experience living,” Misty says, pinning a stray wisp of hair back into her loose bun. We’ve been walking the breezy edge of the Holston, talking about her earlier stint in Los Angeles, when she worked as a stylist and event planner.

“I loved L.A.,” she says, stopping to lean down and dip her fingertips into the river, watching as the water picks paths around them. “But after exercising the horses, harvesting the okra, clearing the brush, I go

home a good kind of tired. I’ve earned my shower. I’ve earned my meal. I just feel so happy and alive.”

She stands and looks out over the fields, her shoulders visibly releasing as she does. Soon she and the sisters will prep the meal for tomorrow’s outing with their Mister Canteen food truck, the traveling arm of their seed-to-table mission. The menu is deceptive. Dishes like savory egg and polenta, Indian fry bread tacos with mashed potatoes and grass-fed Belted Galloway beef, and iced spelt doughnuts seem straighforward but belie labor-intensive roots. The bone broth for soups simmers for thirty-six hours. The hominy is made from their Hickory Cane corn, a three-day process. The sprouted spelt bread is mixed the night before and baked before serving. The doughnuts are fried in hand-rendered lard that is replaced after every use.

“Before we go out, Jennifer is in the garden at sunrise,” Misty explains, now back in Jennifer’s modest house with the sisters. (Both live in former tenant homes on the property, an option Misty is also considering.) “Everything is planted here, collected here, cleaned here. And those same hands are the ones serving you.”

Photo: Squire Fox

“And unfortunately those same hands are washing the dishes later,” Anna quips.

“It is a ridiculous business model,” Jennifer admits. “But we have pride in doing this accurately. No corners cut.”

The women are doing something right. At their last farm dinner, guests were shamelessly smuggling the handmade butter off the table into their purses. This budding success fills the trio with hard-won satisfaction. At the Mister Canteen truck, Anna gives impromptu baking tutorials about spelt to curious doughnut buyers. Misty breaks down the myths about lard. Jennifer shares tips for pasture-raised eggs and chickens.

“We talk all the time about how we are broke and poor, but we are rich in ways most people aren’t,” Anna says. “We have six gallons of milk every day. Four dozen eggs every morning. And we have purpose.”

On her new album, Birdlight, Jennifer sings more than a couple of tunes inspired by the land where she now works and lives, including a whimsical cover of Jimmie Rodgers’s “No Hard Times”:

Got a barrel of flowers, Lord, I got a bucket a lard.

I ain’t got no blues, chickens in my backyard.

Birdlight is an ode to the farm and the curative powers of manual labor. With each verse she reminds listeners how much can be healed by breathing in and looking out, spreading the optimism brought on by her new life to folks who may reside in darker places, as she once did.

“I can cast back and say, when I moved here, the land was being mistreated, it was toxic, and now it is being turned around,” Jennifer says. She smiles wanly, aware. “I know, I know. It’s a metaphor for my life.”

Misty experienced a similar evolution.

“If someone had told me two years ago when I was sitting in traffic on the 405 that I would be wandering around this farm on turkey-slaughter day, collecting feathers,” she says, “I would have laughed. I’ve come such a long way.”

That night, driving home in her truck, windows down, the air bringing in the welcome cool of dusk, Misty speaks about the importance of family—genetic and otherwise—and the value of passing down food knowledge from generation to generation. She explains that, for her, a meal is “not just sustenance, but a work of art, a story to enter into.”

“My hope is that one day people will expect all of their food to come from a place like Riverplains,” she says. “That everyone will believe they are worth that.”

Back at the farm, Frank Niceley couldn’t agree more.

“People in the South like a good meal,” he sums up. “I don’t know about the North, but down here, we care about food. It’s everything.”

Photo: Squire Fox