Food & Drink

Chef Erling Wu-Bower’s Louisiana Roots

The roots of the chef’s acclaimed cooking—and his outlook on life—trace directly back to his Louisiana heritage, a cultural gumbo of bayou fish camps, New Orleans jazz clubs, and a family who gives it to him straight

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Galatoire’s fried soft-shell crabs;chef Erling Wu-Bower checks his fish stock; speckled trout comes aboard.

It’s a bit of an

improvisational

performance

tonight.

For starters, Erling Wu-Bower is a long way from Chicago, where his mash-up of cross-cultural cuisine has won him accolades, including status as a three-time James Beard Award finalist. He’s worked the kitchens at some of the Windy City’s upper-echelon restaurants—among them Avec, the Publican, and Nico Osteria. In the spring of 2018, he opened Pacific Standard Time to glowing write-ups in the New York Times, the Chicago Tribune, Wired, and elsewhere. But he insists that this place feels most like home: the Spartan kitchen of a Louisiana fish camp on stilts, a half dozen ingredients on a rough countertop, fresh fish on the cutting board, a bayou and family close at hand.

Under his gaze, shrimp shells stew in a rich stock. Fresh speckled trout marinate in fennel, shallots, garlic, and wine. At Wu-Bower’s shoulder, his father, Calvin Bower, stirs a roux in a cast-iron pan. Bower is no stranger to performance, either. He grew up in South Louisiana in the 1940s, the son of a Southern Baptist preacher. He learned to play piano and piano accordion so he could lead hymns at his father’s tiny mission churches in Port Sulphur, Belle Chasse, Empire, and Buras. Some of the churches were so small that their congregants paid his father in fish. “‘Blessed Assurance,’ ‘The Old Rugged Cross’—those hymns set my life in its direction,” Bower says. As professor emeritus of musicology at the University of Notre Dame, he now studies the history of sacred music in the Middle Ages. He has served as choir director for the Notre Dame basilica, and recently published an award-winning translation and commentary on the liturgical poetry of the ninth-century Benedictine monk Notker Balbulus.

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Bayou Log Cabins in Port Sulphur, Louisiana.

As did many Cajun children, Bower learned to cook with passion. He was only eight years old when his father gave him a cypress pirogue, a ticket to the fish-rich bayous around Port Sulphur. Today he has andouille sausage and fresh filé—the ground sassafras leaf that is an essential finisher to authentic gumbo—shipped north to his home in Chicago. It’s not a stretch to say that Bower may be the only medieval musicologist who can catch, clean, and cook an alligator gar, and it would be hard to find another Cajun who once owned an apartment in Munich to serve as a locus for his research throughout Europe.

Nor has he forgotten how to chunk bait toward a Gulf of Mexico rock jetty. Listening to the repartee in the kitchen reminds me of a moment earlier in the afternoon, as we were fishing for redfish and trout. It was one of those big-blue-sky sunny days in the pre-pandemic era when cares were held at an arm’s distance, and Wu-Bower and his father stood shoulder to shoulder on the bow of a boat, casting live shrimp toward the rock jetties off Grand Isle as tall, rolling swells lifted and then dropped the boat with knee-jarring force.

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Wu-Bower serves up grilled fish while his father, Calvin Bower, looks on.

“Keep that slack out of the line, Dad,” Wu-Bower admonished. The chef was barefoot, the professor clad in Birkenstocks. It was tough footing on the boat, but still they swung trout over the gunwales, and through it all there was a little dance up on the bow deck, a kind of Cajun two-step as they searched for purchase and balance. And for what would not be the last time over the next few days, it was hard to tell who was leaning into whom.

Back at the fish camp, father and son chop celery, bell pepper, and onion, the holy trinity of Cajun cuisine. Wu-Bower’s half brother Greg, a musician and vintage turntable restorer from Durham, North Carolina, referees the conversation. The “Bower boys,” as Wu-Bower calls this assemblage of family, have invited me to tag along on one of their occasional pilgrimages to South Louisiana, their ancestral home, to cook, fish, eat, and plumb their old haunts in New Orleans. (Another half brother, Georg, is a Colorado Springs–based pilot whose side gig is restoring vintage Honda motorcycles.)

In the kitchen, the pair work in concert, a discordant strain or two evened out with humor.

“I always take the strings out of my celery,” says Bower, slightly stooped and nearly bald, an impish grin tugging at a wiry gray mustache.

Wu-Bower smiles. He knows where this is going. “Those pieces are going to be, like, less than a quarter inch long, Dad.”

“The strings are bitter,” Bower parries.

Wu-Bower’s smile widens. “Celery is bitter,” he says, triumphant.

“Not if you take the strings out.”

His son taps the tip of a chef’s knife on the cutting board, holding his tongue for the moment. “You know, Dad, I’m pretty good at what I do.”

His father relents, but barely. “Look at him,” he says. “He cuts vegetables the way I play scales on the piano. I’m very jealous.”

There is a brief pause. “But I always take the strings out of my celery.”

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Crawfish étouffée; Wu-Bower and his father stirring things up; marinating the day’s haul.

Exactly what Erling Wu-Bower does is a topic he’s curious about himself, especially as he ponders his immediate future. He left Pacific Standard Time last summer and is working on opening a new restaurant that incorporates rooftop-grown vegetables from Chicago office buildings in an organic space that can shape-shift to include, say, a pottery gallery or a pop-up vintage album kiosk. “I want to take the local concept and make it even smaller,” he explains. “I’m more convinced than ever that food isn’t about labels. It’s about story. And I want to tell my own story through what I do next.”

His family story and his culinary expressions are tightly interwoven. He was born in South Bend, Indiana, and moved to Chicago when he was six. His parents divorced, which had at least one fortuitous side effect: As a young child, he traveled extensively with each parent. His mother, Olivia Wu, was a food writer for a suburban Chicago newspaper, the Daily Herald, and then the Chicago Sun-Times. As a child, Wu-Bower trolled Vietnamese markets with his mother and was her go-to date on restaurant assignments. (Olivia Wu moved to a similar position at the San Francisco Chronicle before joining Google in 2007 as an executive chef.) All the while, he was trekking with his father back to Louisiana to visit grandparents in Lafayette, and hitching rides across Europe on Bower’s frequent research trips.

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Speckled trout and mackerel on the grill.

“Some of my best, earliest memories were of being on a train with Dad, traveling across Europe, eating amazing food,” he says. “He would do his research in these grand old libraries while I wandered the nearby streets. It was incredible.”

Bower laughs at the story. When his son was only twelve, Bower recalls, “we went to a very nice French restaurant, and Erling told the waiter, ‘I’ll begin with escargots, and then I want the veal kidneys.’ The waiter looked at me with raised eyebrows, and I knew what he was thinking. Is this really what the kid wants? And for the rest of the night, Erling was the center of attention. They brought him anything he ordered.”

As the shrimp stock thickens, Wu-Bower considers his cross-cultural mix of personal history, deeply rooted in food. “A lot of the soul of my family is rooted in the South,” he says. “Growing up, food was never just food. It was celebrated, analyzed, and discussed at length.”

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Bower tending the pan.

Think about gumbo, he says. It isn’t a thing in and of itself so much as it is an aggregation of other essences. It seems an apt metaphor for his own culinary trajectory, and the vibe of this weekend with his family. “I grew up in an environment where you couldn’t separate the cultural aspects of food from the cooking and eating,” he says, spooning out a sample for a taste. “That’s why I hate recipes. You are, in a sense, stealing someone else’s story. And story is where good food begins.”

Music is also a chief ingredient of the Bower boys’ trips to Louisiana. From the Port Sulphur marshes, we head north to New Orleans. We headquarter at the Pontchartrain Hotel, the grand 1927 Garden District landmark where Tennessee Williams lived as he wrote A Streetcar Named Desire, then sortie out to some of the family’s old haunts.

As undergraduates at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, Bower and a small band of music fans pilgrimaged to New Orleans often. “We stayed in cheap motels on the edge of town,” he recalls. “We were there for Al Hirt and Pete Fountain at long-gone clubs like Pier 600. I was the Baptist preacher’s kid who didn’t drink, so I had to do all the driving.”

Greg Bower listens with one ear turned to his father and the other cocked toward Bourbon Street. While Wu-Bower’s relationship with his father revolves around food, music is the stronger bond for his half brother. “You can’t imagine what music would be like without the New Orleans jazz scene,” Greg says. “Rock and roll, R&B, soul, funk—it’s all intertwined with the jazz, and then you layer in the Cajun music and history, and my dad grew up in the middle of all that. It was the foundation for a stunning career doing things most people have never heard of.” He shakes his head. “It all came together for him right here.”

Many of Bower’s old standby joints are still hopping. At d.b.a., as narrow as a train car and with kaleidoscopic lights playing over old beadboard walls, Walter “Wolfman” Washington is bathed in a green light, playing it all: trombone, saxophone, guitar, bass, drums, and keyboard. We dip in and out of bars, catching snippets of acts, following Bower through the cobbled warrens of the French Quarter.

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

New Orleans’ Preservation Hall.

Preservation Hall proves the strongest draw. Even today the venue is hard to miss, a simple wood-shuttered Creole building built on Saint Peter Street in 1817, a year after a massive fire swept through the French Quarter. Part jazz club, part tourist mecca, and part historic site, it is almost self-consciously pristine. Inside, the building’s original porte cochere serves as a waiting area for ticket holders, musty and dark, with walls covered with old concert posters and vinyl records. In the tiny performance hall, we sit on splintered wood benches only slightly less comfortable than the straight-backed kitchen chairs that support the band players.

Bower remembers firsthand its transformation. He started coming in the late 1950s, when the space was a funky art gallery where the owner invited local jazz musicians to play for tips. It was a fraught moment in New Orleans music history, as traditional jazz was being steamrollered by rock and roll. “There was a movement to find old musicians from the twenties and thirties,” Bower recalls, “and convince them to play again.” Bower joined a nascent organization called the New Orleans Society for the Preservation of Traditional Jazz, which organized shows and jam sessions at the art gallery. Crowds spilled into the streets. The venue was renamed Preservation Hall in 1961, and soon music lovers from around the globe packed the place.

The show is exactly what it purports to be—part cover band, part tribute to the arc of jazz history that draws both acolytes and the simply curious. Bower is decidedly in the first group, a little wild-eyed that he’s back in town, his fuzz of gray hair backlit by the stage lights, and it’s easy to imagine him here as a college kid. As one song winds down, he hollers out a request: “Just a Closer Walk with Thee,” the down-tempo Southern Baptist staple.

He catches the confusion crossing my face. “It’s a classic New Orleans funeral song,” he explains. “At Pier 600, Al Hirt would play it during his third set, and he’d tell people, ‘Put your drinks down now, and be quiet.’ They’ll play it in a Dixieland style. Just listen.”

As the soulful, sacred notes reverberate off the walls, everyone in the room is starstruck. And quiet.

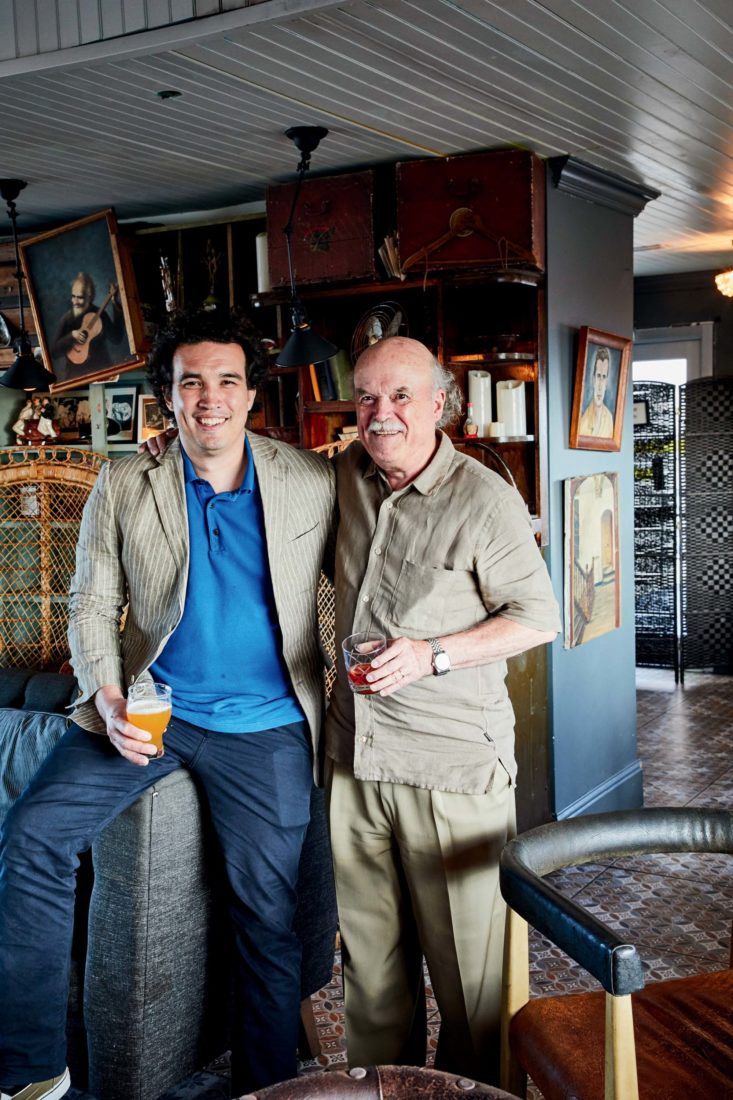

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Wu-Bower and family at Galatoire’s.

Given that our road trip down the culinary and musical lanes of Bower history has been a bit of a French Quarter walk of fame, it’s no surprise that we wind up the night at Galatoire’s Restaurant. The Bourbon Street fixture, dating back five generations, and the famed Commander’s Palace feature as foundational landmarks in Wu-Bower’s culinary journey. He has been here many times with his father, and at the table, he sits with his arm around Bower, patting him on the shoulder in a display of easy warmth.

We start the meal with turtle soup topped with sherry, and Bower is immediately transported. “This is New Orleans!” he exclaims, for the tenth time this evening, and every time he means it. But it doesn’t take long for his focus to narrow from the memorable surroundings to the tureen on the table.

“There’s some kind of thickener in it,” he says, mouth half full, spoon in midair. “I can’t quite place it.”

“It’s roux,” Wu-Bower says. “It’s full of roux.”

“No, not roux,” his father corrects. “Could be the collagen. I taste it. Or maybe I feel it.”

Greg Bower weighs in. “It’s the way it pours. I vote for collagen.”

Wu-Bower shakes his head, outnumbered. He knows good and well it’s roux.

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

At the Pontchartrain Hotel.

His father senses that perhaps he’s pushed a bit hard. He offers a compliment by way of apology.

“In his restaurants, everywhere he’s ever worked, he’s a f**king artist,” Bower tells me. “Even his salads, my God, they’re wonderful.”

“And he’s an artist because you dragged him to places like this,” Greg offers, “all over the world for half his life.”

“True, true,” Bower notes. “But with the salads, you know, I’d still say he uses too much vinegar.”

The table bursts out laughing. “I’m sorry I make food taste bad, Dad,” Wu-Bower says, grinning. His hand never stops rubbing his father’s shoulder.

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Greg and Calvin Bower outside Preservation Hall.

The conversation ricochets between tales about jazz clubs back in the day and unforgettable meals shared the world over. Bower tells the hilarious story of one of his most memorable New Orleans moments. Galatoire’s might offer elevated plates, but it is nonetheless situated in the heart of the Bourbon Street area, a melting pot of tastes, to say the least. Once, Bower was meeting a classics professor from the University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill while at a conference of the American Philological Association, when his professor friend walked up to the table.

“And she was completely flustered,” he says. “She had been horrified by the walk to such a classy restaurant. ‘Did you see what I saw just a few doors down?’ she asked me. ‘Candy underwear!’”

Bower breaks out in uproarious laughter. “Candy underwear! How can you not love this place!”

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Pompano at Galatoire’s; at the Pontchartrain Hotel.

Just then, the waiter, a gentleman named Charles Grimaldi who has worked at the iconic restaurant for thirty-five years, places in front of Bower a fillet of pompano, sautéed and lightly glazed with butter. The conversation stops as Bower looks at the fish as if he were studying a hymnal, then grasps the plate with both hands, pulls it close, and smells the fish deeply, from one side to the other. A smile breaks across his face. He knows it is the most appropriate response imaginable to the wild-caught fish on his plate.

Beside him, Wu-Bower nods approval. Bring it close. Touch it, smell it, use every sense to harvest the essence. It’s not just food, like it’s never just music.