Arts & Culture

Daniel Wallace Explores the Art of Mudlarking

Finding peace and pieces in Southern streams

Photo: Tim Tomkinson

Greetings, fellow mudlarks! You of the boots or old tennis shoes (the ones you bought two summers ago, worn out already, sacrificial footwear) sinking deeper than you may have expected or hoped for into the ever-soft foreshore. But it’s a bargain you make with the elements. Like everything else in this life, it’s about how far you’re willing to go—how dirty are you willing to get? The farther and dirtier the better: We mudlarks know this. Beachcombers are in our family tree, friendly relations, but they are not us. Those of you with no dirt beneath your fingernails, we pity you.

And yet, this is interesting: Though you’ve been one off and on for most of your life, you may not even know it. You may not know what mudlarks really are. You may never have known that digging around in the mud looking for cool stuff had a name, that it was called something other than digging around in the mud looking for cool stuff. But everything has a name, and this thing we do is called mudlarking, a beautiful word for something that is essentially a muckfest, a deep dive into our silty past.

Mudlark. The magic of the word doesn’t wane from repetition, but the beauty of it is deepened by its regrettable history. It’s defined by the New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary on Historical Principles as “a person who scavenges for usable debris in the mud of a river or harbour.” It’s a term that was coined in the latter part of the eighteenth century, in London, describing those who scratched around on the shores of the River Thames. The Thames is a tidal river. It rises and falls by up to twenty-four feet a day. And every day on its shore—the foreshore, it’s called, the part of the shore between the high and low water marks—something is seen that wasn’t seen before. Two hundred years ago in London, the children (most mudlarks were children, or robust older women) took to the water’s edge at low tide hoping to find something, anything, they could sell. By the late nineteenth century, there were almost three hundred of them, scrounging for a living in the river’s muck. Lumps of coal, rope, bones, iron, copper. The children hauled their catch up to the street and sold it for whatever they could get. But there were also incredible treasures to be found: Bronze Age swords, shields, rapiers, Roman coins.

To this day, every day, the tide reveals new ancient things: Mesolithic flints, fragments of bricks and roofing tiles from the Middle Ages, Victorian pottery sherds (not a typo: fancy archaeologists use sherds when referring to broken bits of old pottery, and shards for everything else, like glass, metal, and bone), buttons and handmade marbles, and clay pipes from the 1600s to the early 1800s. The clay pipes were used to smoke tobacco from the New World. They were often sold already filled with tobacco, and once it was consumed, and the pipes themselves burned away with it, they were discarded. Finding these things among the stones that disguise them, it’s impossible not to realize that you are the first person to touch them in hundreds, sometimes thousands of years—Western civilization has been using the Thames as a dumping ground for over two millennia. (Mudlark, by Lara Maiklem, is required reading for those who want to know more.)

The Thames is like a museum that only opens at low tide. It’s a museum of the day-to-day lives of the people who were here—right here on this river—before we were. To mudlark along the Thames now, you need a license. You need to belong to a special club, which is very particular.

But the Thames is not the only place you find mudlarks. There are other rivers.

Photo: Tim Tomkinson

Back in the late sixties, when I was ten years old, I was a mudlark. There was a stream at the bottom of a shallow ravine behind my best friend Jamie’s house, just outside of Birmingham, Alabama. I don’t know where it came from—what larger entity—or even remember wondering. It was just there, a stream that began in one place and ended in another and part of it went through his backyard. It was so narrow you could jump it without having to think about it twice. But this stream (rivulet, runnel, rill—so many great names for tiny rivers) could be anywhere, trickling in the shadows beneath an army of pine trees and oak. There were places where a backlog of sticks slowed the current and created small pools of water. You could see to the bottom and the fine sandy granules of dirt. We would spend large amounts of time here, by this stream. Much of it was spent picking up rocks and seeing what was beneath them: crawdaddies, salamanders, frogs, tadpoles. But kneeling in the mud you could find other things too. Just as it was on the edges of the Thames, in Jamie’s backyard we found glass. Old soda bottles, and the insulators from the top of electrical poles that looked like abandoned parts of alien spacecraft. Lodged between the river rocks were smaller pieces of glass, in the deepest hues of green and blue, small shards worn down until their edges were as soft as a wedding ring. I remember finding an old fork there once, tines bent and burned as if in a campfire; I found some old coins—Lincoln wheat pennies from before I was even born—and a bird’s bleached bones. I also found rusty metal license plates buried in the mud or hidden beneath a pile of leaves. This was a mystery to me. How did a license plate, which was made of metal, and the length and width of a shoebox, get down here? Could it have floated in on a tide during a rainstorm when this stream became a baby river? Or was this wooded ravine a place where people came to disappear? To change their old lives by getting rid of everything that marked them as who they were? They gathered around a campfire, eating beans with this fork, playing card games with pennies, and in the morning set out into the world, never to be seen here again.

There are stories in objects, in the most random things, and this is when you know you’re a mudlark, when you see them.

Beachcombing is what mudlarks do on vacation. We have seen them walking back and forth just beyond the breaking waves as we watch from the deck nursing our first cup of coffee, or second mojito. Most beachcombers are just hoping for a pretty shell or two, a souvenir to remind them of where they went last July. But shells that look pretty glittering wet in the burning sun fade into dullness by the time they get home. Truly, there is not a lot the average surfy beach reveals. Of course, that doesn’t keep your uncle from looking, the one with the metal detector and air-traffic-controller headphones, hoping to find a gold Timex, or maybe half a pair of earrings. No real story there, though. Something was lost and now it’s found. No mystery.

Mudlarking is not about discovery but about liberation, because most of what a mudlark finds was never lost, it was given to the water by its owner deliberately; finding it gives it back the life it lost when its owner was done with it. Mudlarks only find what the river wants to give them.

Serendipitous happenstance is enough sometimes. Or simple beauty. But soon you’ll want context. It’s no longer simply What is this? but Why is this? Why is this here? An aimless walk along the banks when you see something unnatural in nature. Shards of the past from a broken bottle, or something that just might be an arrowhead, and your eyes home in on the space around your feet. Mudlarks call this “getting your eyes in.”

Some of the best mudlarking is done among remnants from earlier centuries. In Charleston, South Carolina, there’s a slip of sand along the Battery where people dumped trash in the early nineteenth century. Just strolling along near there, you can find a lot of ceramic fragments, like Mocha ware or china. Everyone had Mocha ware back in the nineteenth century because it was so cheap, and when it broke, they’d just throw it out. Now it’s amazingly expensive. But find a piece of Mocha ware in Charleston and you have to wonder how it got here. It wasn’t made here. It was shipped here from England, and some early Americans ate their supper on it. One of the kids came hurtling through the dining room and slammed against the table, busting the dinner plates. Into the harbor they went. It’s just a story. It’s storytelling through objects. You might find it on your lunch break, pick it up—the first person to touch it in a hundred years. The first person since it was unceremoniously tossed.

The electric thrill of that touch is addictive. True mudlarks can’t stop. It’s as if they’re trying to reassemble the world.

The globally renowned self-taught artist Butch Anthony has been a mudlark almost all of his peripatetic life. He lives in the unincorporated community of Seale, Alabama, not far from the Georgia state line, and about two and a half hours from where I grew up in Birmingham. When he was fourteen, he dug up a vertebra from a mosasaur, a seventy-million-year-old fifty-foot-long lizard; now, though near half a century has passed, he has not slowed down a bit. But it’s not about extinct reptiles anymore, it’s about his art. On the Chattahoochee River, near Columbus, Georgia, sandbanks appear when the river dries up, spangled with all sorts of things, mostly glass, old bottles especially: Columbus opened a Coca-Cola bottling plant in 1902.

“There’s a bridge there, and everyone has been throwing their stuff off of it for a long time,” he says. He spots things around the bridge and in the water—whatever beautiful refuse finds its way to the surface. He calls his signature style Intertwangelism, a word he made up that describes his way of assembling art, design, and objects from nature. To him, inter = to mix, twangle = a distinctive way of speaking, thinking, behaving, and ism = a theory.

Storytelling is central to Anthony’s work. And it’s a magical restoration of sorts: finding something once considered functional, and turning it into something that is proudly not, an art that exists for its own sake, a collaboration with an unnamed teenager from 1953, throwing back the last of his cola and thoughtlessly dropping the bottle into the Chattahoochee.

Photo: Tim Tomkinson

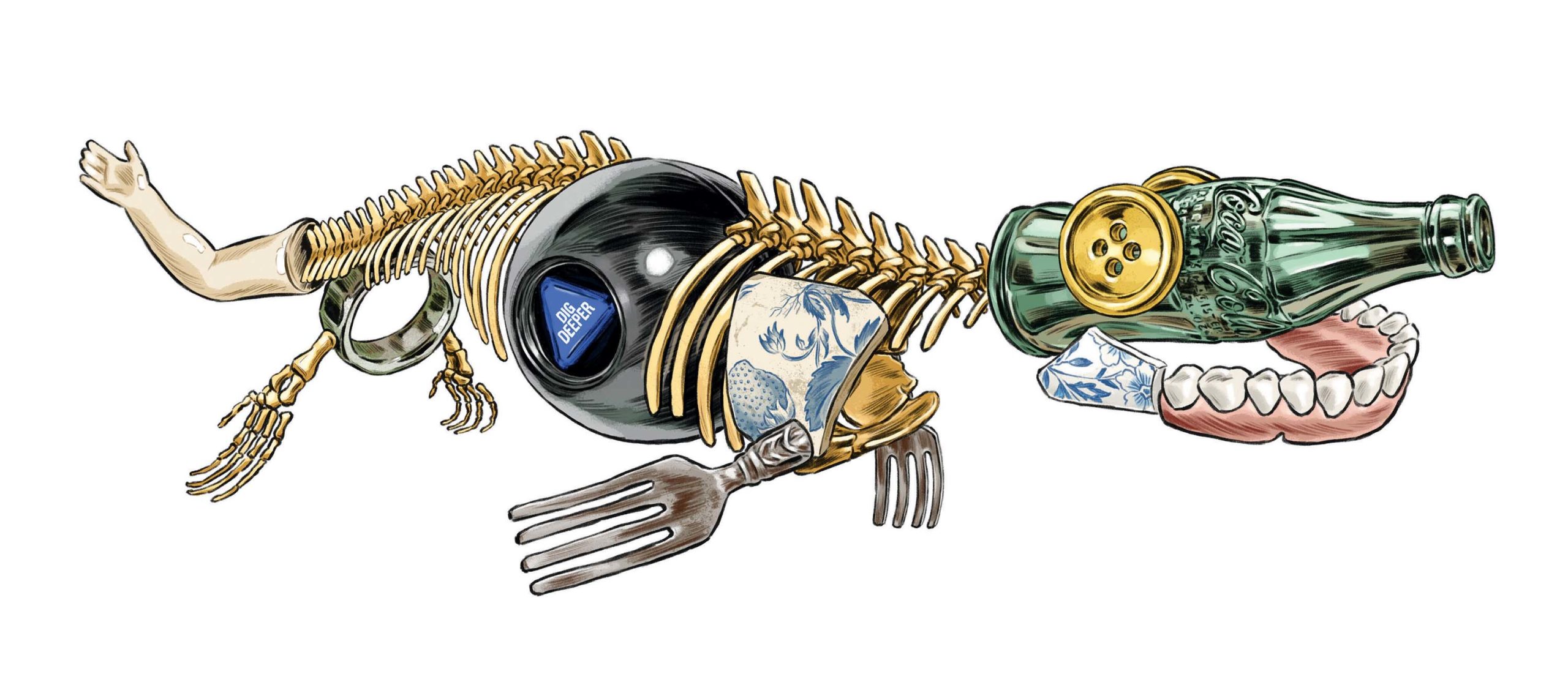

No matter who they are or where they’re doing it, mudlarks are treasure seekers, but their treasure is, literally, the trash of other people long dead. And this leads to questions: What is the process by which rubbish attains value? How much time has to pass before, say, a zirconium wedding ring or a set of false teeth or a Magic 8-Ball becomes a prize? Some serious scavengers dig up outhouses and seek out antebellum rat nests, rats being great collectors themselves. When will my father’s ashtrays, which we threw into Chesapeake Bay, make somebody’s day? I will hazard this answer: When enough time has passed that the object has a secret, a story to tell, one that we may never know the particulars of, but one you can happily spend a few moments imagining. That’s the difference between today’s mudlarks and the world’s more common scavengers: dumpster divers, junkmen, waste pickers, grubbers. There is almost no monetary value in what a mudlark finds; almost none of what they find is whole. Joy comes from finding a piece of something: a piece of brick, of a pipe, of a plate. A fork with bent tines. These are clues, clues pointing toward a larger mystery.

That larger mystery is us.

All of us are mudlarks, forever digging into the mucky and murky past for remnants of who we were, in the hopes that by bringing these small broken parts of ourselves into the light, we’ll understand the greater whole. And maybe we’ll learn to be as careful about the things we throw away as we are about the things we keep.

Water subsumes and reveals us. We will find more of the old world as waters recede in coming droughts, and lose more of the new world as glaciers melt, pouring into and over our coastal towns and cities, setting the table for future mudlarks farther inland. And all of our future selves will wonder who we really were to have done what we did. Think of what we’ve had and lost, carelessly disposed of, and of the young just now being born who will go out looking for it all, and tell stories about what they find.

This article appears in the August/September 2020 issue of Garden & Gun. Start your subscription here or give a gift subscription here.