Drinks

High Plains Vintners

Amid drought and freezes in a rugged stretch of the Lone Star State, winemakers are blazing a trail toward a true taste of Texas

Photo: Joel Salcido

Lonesome Vines

Grapes grow at Lost Draw Vineyards, near Brownfield, Texas.

I looked down from the 757 at crop circles cut in dirt by irrigators on wheels, a vast dun-colored landscape pinned to the geology by galloping telephone poles. The plane landed in a dust storm, with me trying to imagine how people—much less grapevines—lived here. I had come looking for the origins of the best wine in Texas, knowing that the state wins its share of medals in national wine taste-offs and has a glitzy, Napa-wannabe wine trail in the Hill Country near Austin and San Antonio. But I also knew that, if there was soul in those bottles, most likely it arrived in tanker trucks after a six-hour hard haul from much farther west, starting right here on the Texas High Plains.

People like to say there’s nothing between the THP and the North Pole to stop the wind but barbed wire. The area is also called the Llano Estacado—the Palisaded Plain, or, more commonly, the Staked Plain—and at up to 5,000 feet in altitude a testament to endurance and conquistadorial madness. Coronado passed through in 1541, looking for a city of gold, and found more or less what you find today with the exception of assorted structures protruding from the 360-degree horizon. Disoriented, harassed by Comanche, Coronado ordered his soldiers to drive stakes into the ground, according to local lore, so he could find his way back to Mexico.

There were no fine wine grapes on the Llano Estacado in those days, but now dozens of European varieties of Vitis vinifera grow here, and from them flow good wine and good stories. Like that of the man who met me outside the Lubbock airport in an old pickup. He wore Levi’s, a plaid shirt, a down vest, and sneakers (cowboy boots don’t cut it on cold concrete winery floors). The crease in his graying beard was full of white teeth. “Gol-lee,” he said, “it’s almost seventy degrees, and tonight it’s dropping into the twenties. Welcome to West Texas.”

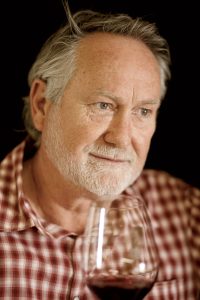

He was Kim McPherson. His father, Doc McPherson, was a chemistry professor at Texas Tech and a true pioneer of the state’s modern-era wine industry. Back in the sixties, Doc and a colleague found vines that researchers had thrown out and planted them next to Doc’s patio, without knowing exactly what they were. Some flourished, proving that fine wine grapes could take the climate. (Doc also tried planting grapevines from Spain that one of his students had wrapped around the rims of a used VW Bug and smuggled over aboard a ship.) From these serendipities sprang an industry and a way of life no one predicted for the THP.

In the seventies Doc and his friend started a winery called Llano Estacado on the outskirts of Lubbock. Though they later sold out, the winery remains part of the McPherson legacy and is now the second largest producer in the state, bottling upwards of 180,000 cases annually. Texas as a whole now makes about 1.2 million cases of wine a year, although it remains a vinous puppy compared with, say, Bordeaux or California. (Little Napa Valley alone produces enough grapes for some 9 million cases.) Wine was made in Texas out of various fruits from early on, but Prohibition shut down what little commercial production had once existed. Now, the industry is growing rapidly—270 wineries at last count. So far, however, the national swirl-and-sniff press hasn’t given Texas wine much good ink, the general belief among critics being that the state concentrates too heavily on its swilling tourist trade.

The THP is the second largest viticultural area in Texas, behind the Hill Country, but it has a bare handful of wineries and, so far, an overall paucity of fruit. Llano Estacado is by far the area’s largest winery, and it has to buy grapes and juice from elsewhere, including New Mexico and California, to meet ambitious commercial goals. McPherson Cellars, started in Lubbock by ole Doc’s son in 2000, has a tenth of Llano Estacado’s production, and though it too may supplement on occasion, the vast majority of its wines are made only with grapes grown right there on the plains.

Kim McPherson believes strongly in terroir, the unique combination of soil and climate that creates truly distinctive wine. This has gained him a considerable following in Texas and beyond. It was Kim to whom I was referred whenever I asked knowledgeable people about Lone Star viticulture, one adding pointedly, “He’s an individualist.” A vineyardist told me, “Kim can be blunt. I wasn’t sure I wanted to get into business with him. Thank God I did.”

Photo: Joel Salcido

Texas Terroir

A small sand dune at the edge of a vineyard.

Kim drove me past the Buddy Holly Center and the old Cactus movie theater, along sparsely populated streets typical of small Western cities that emptied decades ago and are beginning to refill as suburbanites seek better schools and something to do at night. He pulled in behind a low building on Texas Avenue left over from the thirties, a classic example of art deco and functional minimalism that had once been the local Coca-Cola bottling plant.

“I wanted to hear the fire engines,” he said, of his decision to build his winery here, instead of out on the plains. The long, curvilinear “pillbox” window on the sidewalk that once offered a view of Coke’s bottling line now revealed visitors happily bending their elbows next to stemmed glasses of red and white wine. We joined them and in the next hour went through a dozen McPherson wines from screw-cap bottles, a proven technology still not embraced by traditionalists but accepted by edgier winemakers.

What surprised me about the wines was their quality, and consistency. No matter what grape had gone into the bottle, they all had originated in hot European climates, and all had a recognizable McPherson signature: balance, structure, and lean, bright fruit well suited to assertive food.

“We’re the Ribera of America,” Kim said, a reference to the Ribera del Duero, one of Spain’s choice wine-producing districts on the dry, rocky northern plateau. It produces Tempranillo, Mourvèdre, and other varieties Kim thinks best suited to the THP. “The fruit behaves a little different here,” because of the extremes of temperature. “During growing season it’s ninety degrees during the day and sometimes forty at night. So we get great color and body.”

Photo: Joel Salcido

The McPherson winery in Lubbock.

He grows some cabernet sauvignon—still the darling of American red wines—in a small legacy vineyard started by his father, but he isn’t really interested in grape varieties from Bordeaux. “When I mention merlot to Kim,” one of his growers told me, “he makes a spitting sound.”

My favorite McPherson red was La Herencia, which means “inheritance.” (“Which I’ve spent,” Kim added.) The wine’s a blend of mostly Tempranillo with Carignan, Grenache, and Mourvèdre, all widely used in Spain, and Syrah from the hot Rhône Valley in southern France. Kim doesn’t hesitate to blend grapes associated with different countries, and even mixes colors, a no-no in more genteel climes. (His Tre Colore is a blend of Carignan, Mourvèdre, and Viognier, a white Rhône variety that does exceptionally well on the THP.) I also liked his unblended Roussanne, a full-bodied Rhône white.

The McPhersons, father and son, have the reputation as the collective patriarchs of Texas wine. It was Doc who encouraged Kim to attend the University of California at Davis to learn winemaking, and later urged him to leave the less-stressful winemaking in NoCal to return to Texas and make wine for Llano Estacado Winery. A dutiful son, Kim complied, saying only, “I didn’t think you’d insist, Doc.”

Kim said of his time in Napa, where he worked for Trefethen Family Vineyards and others and knew many of the people who went on to enological fame, “I didn’t give a big one about the Texas High Plains then. Now I’d love to get four or five guys here together, the ones that do a really good job, and put on a dog and pony show. Bring Texas wines to the forefront.”

Eventually Kim went out on his own—with Doc’s encouragement—and has since been recognized as the THP’s vinous Yoda. Doc himself had died just a few months before my visit, at age ninety-five. “Doc’s old ticker finally wore out,” Kim said, without elaboration.

We crossed the street to La Diosa (the Goddess) Cellars, a bistro run by Kim’s wife, Sylvia. It reminded me of an upscale cantina—dark tiles, Spanish art on the walls, good smells. A lean hombre in a black shirt sat alone at the bar. He said as we passed, without turning around, “They’ve run out of Herencia,” an ominous pronouncement. The scene was straight out of the 1890s except that the man wasn’t talking hooch but wine made fifty yards from where he sat. And it wasn’t a double-action Colt, the weapon that enabled Texans to prevail over the Comanche, next to his hand, but a luminous iPad.

Photo: Joel Salcido

Barrel Fever

Sherry ages in the sun outside McPherson.

Kim and I sat at a table and I ordered homemade empanadas. We drank tea but kept talking wine. Herencia costs $14 a bottle and could sell for twice that, if the world knew about it. So could many of Kim’s wines. “Down in the Hill Country you could get forty dollars for it,” he said. “That’s pretty spendy.” I asked why he didn’t price them higher. “I like to think of myself as a friend of the workingman,” and he added, “Millennials like these oddball wines.” While older American wine drinkers are stuck in the high-alcohol cabernet/chardonnay ditch, unglamorous varietals like Tempranillo, Sangiovese, Mourvèdre, Aglianico, and Albariño are cruising past in stemmed glasses held by thirty-somethings.

That night in my hotel room I listened to the wind on the other side of sealed windows. When I swept back the drapes, I saw a layer of dust on the sill and, outside, light poles bobbing in the horizontal gale. There was snow on the ground, and a few hours before it had been seventy degrees. This climate would give anything color and body.

One of Kim’s growers, Andy Timmons, picked me up the next morning and we headed west across flat, dry farmland, past Ropesville (“Ropes”), the soil on one side of the road a reddish color signifying iron, on the other a chocolate brown studded with old cotton stalks. I had encountered reminders of the Deep South other than the Coca-Cola bottling plant—towering lemon meringue pies and “chicken fried chicken” at the Cast Iron Grill, for instance—but cotton was the strongest. Lubbock had been named for Colonel Thomas S. Lubbock, a former Confederate officer and a Texas Ranger. Texas got plenty of Southern farmers after the Civil War who left notes on kitchen tables at home, scrawled with the letters “GTT,” familiar to many a left-behind wife and sweetheart: Gone to Texas. Today, cotton is still the state’s foremost crop, far ahead of grapes. Yet new vineyards were being planted even as we rode.

Timmons wore a little goatee and drove his big four-door Ram pickup—“the Texas truck”—with care. “Grapes don’t like wet feet,” he said. “There’s clay in this red dirt, where the vines grow best, but not enough to prevent good drainage.” The stress vines need to build character, he added, includes minimal rainfall that limits grape size and concentrates flavor. But with only about nineteen inches of rain a year, and ambient moisture often as low as 15 percent, the THP can have too much of a good thing. “Grapes get a little shrivel on them,” he said, when wind moves towers of dust, haboob-like, across the land.

Irrigation is a desperate standoff between the twin specters of evaporation and a falling water table. The THP sits at the dead end of the abused Ogallala Aquifer, which starts up in South Dakota. Growers use drip irrigation, just as in California, but many bury their lines to minimize evaporation—and then have to dig them up again after they freeze. Sudden frost often arrives late in the spring, as it did in 2013, the harvest from hell when vines were struck three times during bud break and the forming grapes dropped to the ground. Then in early May the temperature fell to 26 degrees, and 80 percent of that harvest gave up the ghost.

Timmons had daringly installed four wind machines at a cost of more than $30,000 apiece as frost protection. The traditional method—coating the clusters with water, which in a cold snap will freeze and thus protect the grape inside—was too expensive because of the cost of water. The machines come on automatically at 32 degrees and temporarily move cold air out of the vineyard, a system that works in isolated valleys but until Timmons’s gamble had never been proved on the THP.

Photo: Joel Salcido

A wind machine to protect grapes from frost.

“People think I’m crazy,” he said, “but all you need to do to justify the cost is save one vintage.” That in itself indicates just how valuable are grapes capable of producing fine wine. As it turned out, this past spring would prove to be the worst yet for grapes on the THP, and Timmons’s wind machines indeed saved much of his crop.

Quality grapes can’t be grown just anywhere. The THP has real terroir, as Kim McPherson and others were demonstrating. The demand for good grapes already outstrips what the state grows. The common sense of planting hot-climate varieties here, despite their difficulties of survival, is as clear as a windless morning, but identifying the best blends, after the grapes have become wine, is still a work in progress.

Such experiments must have once been conducted in Greece, Sicily, Tuscany, Rioja, the Rhône Valley, Bordeaux. The THP shares a living provenance going back to prehistoric times in the Ural Mountains, on the other side of the earth, where Vitis vinifera came from. The THP’s search for what Andy Timmons called “the Texas taste”—a signature of quality and subtle distinction—could well have been called “the Mesopotamian taste” millennia ago. Listening to him, I had a vision of some THP blend dancing in a bottle labeled “Plainage,” or “Mirage,” sitting on a restaurant table in Chicago, New York, London, Madrid, or Beijing.

Photo: Joel Salcido

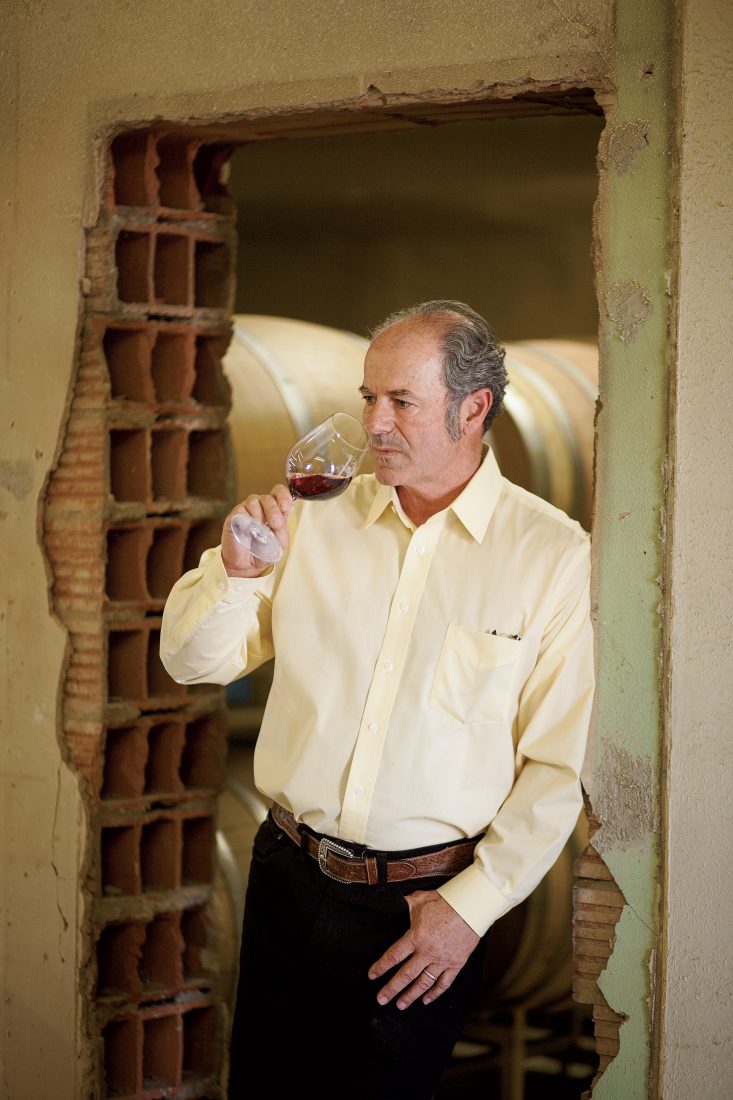

Greg Bruni, of Llano Estacado Winery.

Unexpected lines cross in the THP: ethnic, historic, viticultural. Coronado’s failed expedition left behind a lot of destruction but also made a cultural addition to native Mesoamerica. It’s ironic that his country is also the origin of so many of the grapes that are proving themselves here, in intensely flavorful wine conjuring up distant landscapes as it washes down a shaving of Manchego or a fajita, some foie gras or a braised short rib.

“We’re still trying to figure it out,” I was told by the head winemaker at Llano Estacado Winery, Greg Bruni. He had taken me out to see one more vineyard, reinforcing the maxim that without good grapes you can’t make good wine. Bruni wore a padded Windbreaker between himself and the elements, and he gestured affectionately toward gnarly old cabernet sauvignon vines—“cab sauv”—planted by an Indian from Mumbai named Vijay Reddy, a soil scientist.

“These grapes are blended with our Sangiovese to produce Viviano,” he said, referring to a Llano Estacado wine and a “super Texan,” a special category. (The same blend was used in the seventies in Tuscany, where the Italians called it “super Tuscan.”) Viviano was the first Texas wine I had ever tasted, and that mouthful of flavor had brought me to West Texas, only to learn that cabernet is far from the backbone of winemaking on the Llano. Reddy, for instance, was growing twenty-eight other varieties as well.

Bruni worked for fourteen years in wineries in the Santa Cruz Mountains and could have climbed more in NoCal’s vinous meritocracy, just as Kim McPherson could have. He had recently gotten a dose of perspective on what he and his High Plains colleagues are up against when he visited Napa and told a viticulturist there about the THP’s drought, wind, dust, hail, brutal winters, and bud-killing frosts. “He said, ‘I don’t know what to tell you. We don’t have any of those problems. My main job is not to screw things up that happen naturally.’”

The hardship and the uncertainty of any given harvest seem to unite THP winemakers in common cause. Llano Estacado Winery may make ten times as much wine as McPherson Cellars, but the two are intimately linked. “Kim makes such beautiful wines,” Bruni said. “We’re lucky to have him here. I’ve known him for twenty years and feel like he’s a brother.” He added, “It’s all about pioneering. The struggle requires passion, and we’ve got that here on the High Plains.”