Home & Garden

Inside Julia Reed’s Delta Dream Home

The author called upon friends both far and near to help design and build the house of her dreams—a place for raucous good times and soulful silence—in the Mississippi Delta

Photo: Paul Costello

The main room has fourteen-foot ceilings and serves as library, dining area, and sitting room. The sofa is slipcovered in Le Manach Palmyre from Pierre Frey, and the lanterns are from Jamb in London.

My house in the Mississippi Delta was born on a legal pad in Birmingham’s Highlands Bar & Grill over martinis with the gifted architect James Carter. That was in the winter of 2017, but its gestation had begun decades earlier. Almost ever since I’d left it for good, I’d been dreaming of a get-away in the place where I grew up, where so much and so many people that I hold dear still exist. Where I could let loose, ride a horse, throw a party on a sandbar, drive the levee at sunset, soak up the loamy chemical smell that is more powerful to me than any madeleine. There was my parents’ house, of course, but much as I love them, sleeping in my brother’s childhood twin bed was not what I’d been imagining. I needed a room, a house, albeit a small one, of my own. Toward the end of my marriage, the need became more urgent. I brought my friend Ellen to visit for the first time and she said she could feel my whole being exhale as soon as we crossed into the flatlands from the hills. When my mother announced she was selling our house, that did it—there was a sliver of land separated from our deep backyard by a tall wooden fence. It sat across a dirt road from the pasture where I once kept my horse and felt like it was much farther into the country than it actually was. “Don’t sell the land!” I shrieked into the phone. She didn’t, but she and pretty much everybody else told me I was crazy: There’s no hookup for gas, water, or electricity; the resale value will be laughable; you don’t really want to do this, you just think you do. As a child I was told—a lot—that I was hardheaded. Maybe, but even then I knew my own mind. In this case, my mind and my heart told me that this was exactly—finally—right.

Photo: Paul Costello

William Dunlap’s Trout Rouge and John Alexander’s Monkey Boy hang above an English bar trolley.

Not long after that first meeting with James, he’d translated our felt-tip scribbles and my breathless wish list into a preliminary plan and a gorgeous drawing of a green house with lightish blue shutters and a veranda covered in the orange trumpet vine I’d always pictured. (It’s strange what gets in your head and stays there.) Essentially one pavilion-like room separated from the bedroom by a wall of bookshelves, the house has a wing on one side for a powder room, bath, and dressing room. On the other, there’s a kitchen and mudroom. It’s small, not quite fifteen hundred square feet, but as soon as I saw the plan’s fourteen-foot ceilings and soaring windows and doors, I knew it would feel like a light-filled cathedral.

Photo: Paul Costello

Books piled into an English Regency wine cooler from Niall Smith beneath an Irish Regency console.

James also made gorgeous interior drawings, which were especially fun because he knew all my stuff. Between one pair of windows he drew a fireplace; between the pair on the opposite wall he placed the enormous portrait of a cricket player that had been my great-grandmother’s above a nonexistent Regency console (I found a similar Irish one I love on 1stdibs) flanked by the same great-grandmother’s needle-point Queen Anne chairs. His purpose had been to show me the scale of the windows, but it was a perfect tableau, so I copied it exactly. To help flesh out everything else, we both knew whom to call: our close mutual pals Courtney Coleman and Bill Brockschmidt, partners in a New York– and (now) New Orleans–based design firm whose color sense I adore and who had designed Keith and Jon Meacham’s Nashville house, where I occasionally bunk.

Photo: Paul Costello

The house from the front meadow of daffodils.

I knew we’d have a blast collaborating (I have long called upon them for design advice large and small), and as devoted attendees of the annual Delta Hot Tamale Festival, they already understood the culture. For our first powwow, they arrived with a stack of paint decks as well as a folder of magical colors from a Belgian company called Emery & Cie. Usually I agonize over endless swaths of possible choices and drive myself and everybody else insane. But within minutes, we’d chosen the colors for the exterior (Benjamin Moore Great Barrington Green, named after one of my favorite towns in Massachusetts) and the shutters (Farrow & Ball Oval Room Blue). Inside, in the main space, we were driven by the crusty ocher trumeau procured from my mother to hang above the fireplace. I’d always thrilled to those French houses done up with gray-green woodwork and ocher walls, but since the mirror was ocher, the scheme was flipped. Emery & Cie had the perfect shades for both, so we kept going, choosing Absinthe for the bedroom walls and a chalky white for the ceilings. For the kitchen cabinets, I’d been thinking safe and dark, but Courtney pushed me toward a more exuberant deep turquoise, and even the painters agreed.

Photo: Paul Costello

Kitchen cabinets painted in Farrow & Ball’s Vardo.

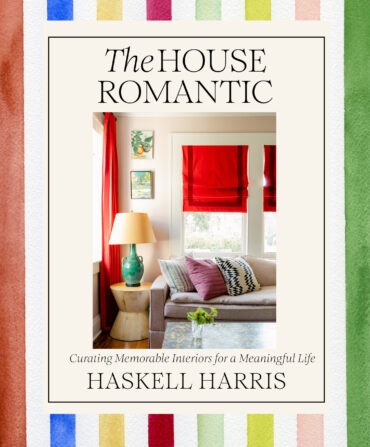

The thing about having something fester in your brain for so long is that you collect piles of images to fuel the dream. The wide-plank walls and ceilings were inspired by the brilliant Furlow Gatewood, whose collection of extraordinary houses I’d written about in One Man’s Folly. Long before the plans were finished, I’d printed out a divine Pierre Frey chintz I’d spotted on Instagram, and then Courtney and Bill sent me the same swatch in the mail. Clearly meant to be, it went on the living room sofa, and everything else followed—the jewel-like blue velvet ottoman, the blue striped daybed mattress, a pretty pink-and-white print on the wing chair from my mother’s living room. For my bedroom, I had a headboard, bed skirt, and chair in a favorite Claremont fabric from an earlier guest room. The talented designer (and super-nice man) Markham Roberts combined the same fabric with a floral chintz in a room I’d seen in his book, Decorating the Way I See It. It inspired me to do the same and we hit immediately on an old favorite, Bailey Rose, which was used for the bed hangings I’d always wanted and to upholster the settee.

Photo: Paul Costello

The bed’s headboard and pillow are covered in Claremont’s Butterfly Vert. The hangings are Cowtan and Tout’s Bailey Rose.

Photo: Paul Costello

A collection of bird prints surrounds the mirror above the desk in the bedroom.

If working with Courtney and Bill was a dream experience, the same was, naturally, not the case with the actual construction. The first team was led by the aptly named Mr. Wanker (who I feel sure is unfamiliar with the spot-on British epithet that is his name). One day I arrived in town to find that twenty feet of concrete had been poured for a five-foot porch (overhang, really) off my bedroom. “I did not ask for a suburban patio,” I bellowed onto deaf ears. They were either incapable of reading James’s meticulously drawn plans or they simply ignored them. The windows were hung six inches too high, which was not the biggest of deals except that the bookshelves had to be reconfigured to line up with them. By then I’d found a new crew led by Tommy Carnell and his right-hand man, Derrick, who are loaded with a ton of actual talent and whom I now think of as beloved big brothers though I keep forgetting I’m the one who is older. It was Tommy who called to tell me that when he tried to plant grass seed, he hit concrete an inch below the dirt—the previous morons hadn’t bothered to get rid of my “patio,” just to camouflage it. Similar gifts emerged. Just the other day I realized the fireplace is not actually centered between the windows. Thank God for the plain wooden interior shutters that fold back and throw the eye off just enough.

Photo: Paul Costello

The dining area with a view into the powder room. On the table are Herend service plates in raspberry Chinese Bouquet, antique luncheon plates from Reed’s collection, and Reed Smythe & Company goblets in Original Green.

But such is my happiness quotient in this house that the irritating mistakes (and those are by no means all of them) do not matter. The house took a village to complete, and it has welcomed a village since. Before I moved in, the ever-generous Howard Christian flew down from New York to help me organize countless boxes of books; his housewarming present to me was a collection of two thousand daffodil bulbs that bloom from March until May, an order he duplicated last fall. On the first Thanksgiving, when the house was still very much a work in progress and the gas had only just been hooked up to the stove, Ellen Stimson (the same Ellen who commented on my Delta transformation) and her whole enchanting family made the trek from Vermont with homemade pies in hand. The next night we blessed the house in a decidedly raucous ceremony scripted by my überspiritual (and spirited) friend Courtney Cowart, a doctor of theology in the Episcopal Church. (Ellen’s son Eli blessed the bathtub—we were thorough.) Hank Burdine (who did lots to shepherd the house into being, including finding the nine-inch-wide pine boards for the floor) made his famous duck poppers, I made crawfish étouffée, and Eden Brent played rollicking blues late into the night while everyone sang along, including my always game father and my sweet, sweet mother, who became an early convert and had everything to do with making the house, my hard-fought folly, happen.

Photo: Paul Costello

A view of the powder room from the bath; a view of the toolshed through the copper screen of one of the two front doors.

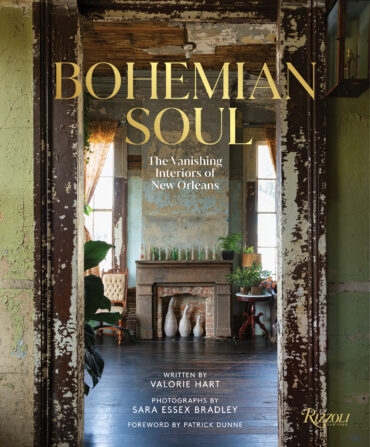

That was less than two years ago, and since then I’ve had two Christmas parties, a catfish fry featuring a gospel choir, and dozens of small get-togethers. It also serves as a soulful (and soul-filling) retreat for my dog, Henry, and me, a place where I’m surrounded by most of my books and all of my music, paintings by my dearest John Alexander and Bill Dunlap, photographs by Jessica Lange and Jack Spencer. Early on, as a joke that stuck, I dubbed the house the Delta Folly, since it seemed to fulfill two definitions of the term: “lack of good sense” and “a costly ornamental building with no practical purpose.” There’s no question that I don’t always have good sense. But the Folly’s purpose manifests itself to me in new and wondrous ways every day, and I am grateful.

Photo: Paul Costello

A Directoire sideboard provides storage in the mudroom, where Henry waits patiently by the back door.

This article appears in the June/July 2020 issue of Garden & Gun. Start your subscription here or give a gift subscription here.