Southern Masters

Meet Ron Rash, the Blue-Collar Bard

The poet, short story writer, and novelist reflects his workaday Appalachian roots in his writing, including a new novella that returns to the antihero of his best-selling Serena

Photo: Daniel Dent

“I’ve never had much of a social life,”

the poet and fiction writer Ron Rash admitted on a video call one day last spring. He had just returned from fishing for brook trout near his home in upstate South Carolina, and he was pleased to have caught one, as well as a snake he came across in the woods: a black racer. His wife, Ann, crossed the frame with a knowing shrug.

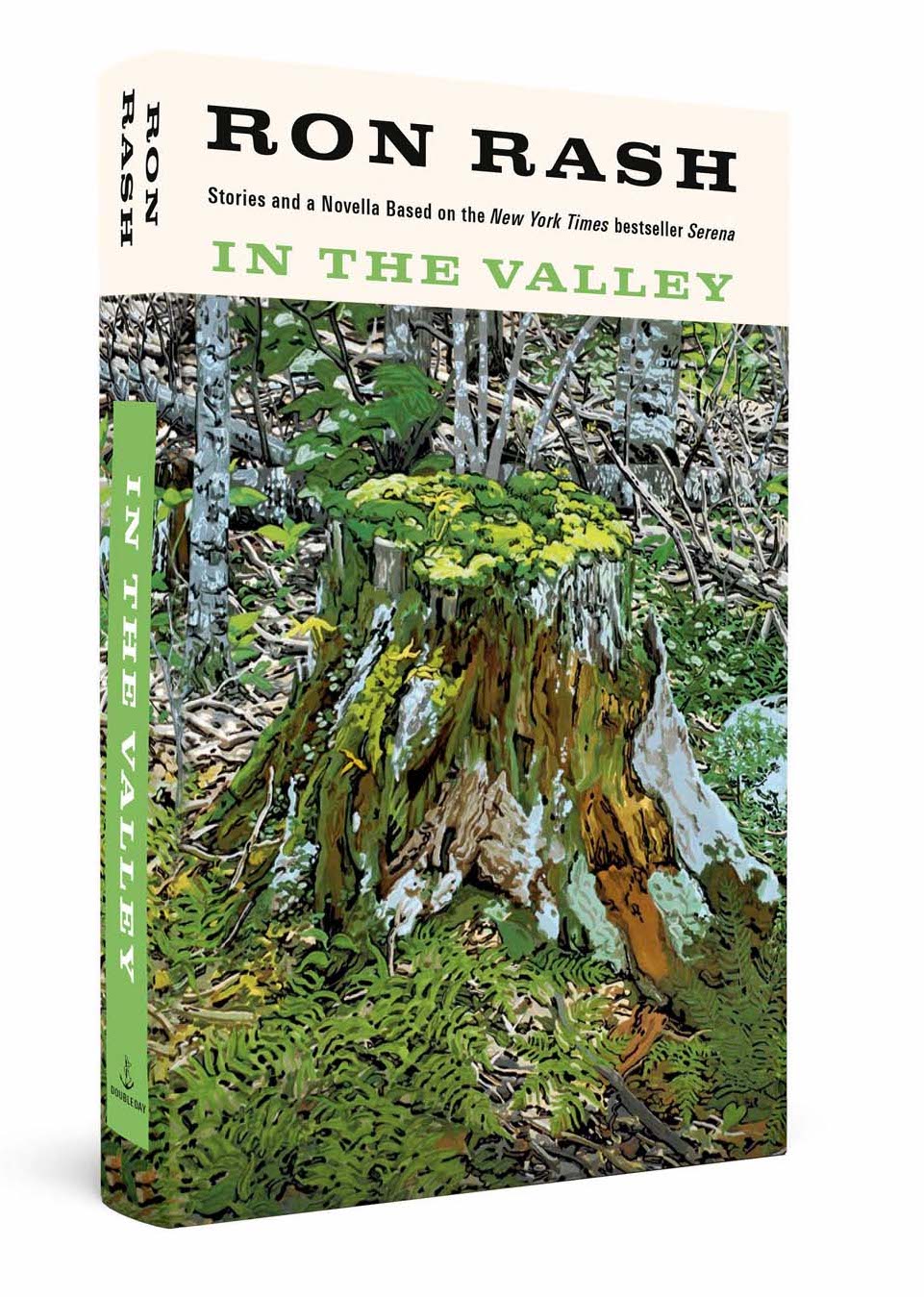

In a parallel universe, Rash would have been preparing for a book tour to promote his latest collection of stories and a novella, In the Valley, or traveling between Clemson and his other home in Cullowhee, North Carolina, where he teaches fiction writing at Western Carolina University. But the world had instead mostly ground to a halt.

Rash, though, has built his life around long stretches of solitude, so his daily rituals went on as they have for almost forty years. First comes forty-five minutes of reading while working out on an elliptical machine. “It opens me up, to get the endorphins going,” he says. Now that he is sixty-six, his knees can no longer handle the strain of running the eight hundred meters, much less in the blistering 1:53 he did in college, or the ten- and twelve-mile jogs that used to clear his head, but for Rash, sweating and writing are twin engines. One doesn’t work well without the other.

Once his workout is complete, he typically spends three or four hours scratching away at a legal pad with a freshly sharpened pencil. He doesn’t trust the smooth, uniform look of his sentences on a computer screen, at least not at first. Using paper and pencil feels more intimate, more like real physical work. When he needs a boost, he reaches for a glass of unsweetened iced tea, and can polish off forty-eight ounces of it before finally putting the manuscript away.

I first met Ron in 2007 when we spoke on a panel together at the University of South Carolina. Then, as now, he was lanky, slightly grizzled, and thoroughly unpretentious, possessed of both a quiet intensity and a warm, self-deprecating sense of humor. His strong mountain accent rounded “writer” into “rider,” giving the trade a slight heroic tenor, and his riffs on world literature—Yeats, Marlowe, Australian fiction—exuded both wisdom and passion. Was my first name, he asked, a reference to the series of early Welsh myths, the Mabinogion? Sadly, no, but his query inspired me to seek it out.

What struck me most was his unwavering commitment to the daily act of writing. Many writers claim to work every day, but I can count on three fingers the ones I know who actually do. Rash is more disciplined than any, writing six days a week, fifty-two weeks a year. Like Dale, the aging dock builder in one of his new stories, he focuses more on process than results: “Even if they never notice,” Dale tells his impatient son, “it has to be done right.” Faced with clumsy first efforts, stalled drafts, and painful rejections, Rash has maintained a stubborn, even irrational belief that if he sits with a story long enough, he might approach that vanishing horizon some call transcendence. “The days you’d rather stick pencils in your eyes than write,” he says, “are the days that’ll make you a writer.”

That tenacity has yielded a wide-ranging body of work—seven novels, seven books of short stories, six books of poems, two anthologies, and a children’s book over the past twenty-six years—all set in the deep folds of Southern Appalachia. In the Valley includes Rash’s first novella, which continues the saga of Serena Pemberton, the ruthless logging magnate from his 2008 best-selling novel, Serena.

Though Rash doesn’t write to please critics, they sure seem to like him. Janet Maslin of the New York Times considers him “one of the great American authors at work today,” and she is not alone. He has received the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award, a Sherwood Anderson Prize, two O. Henry Prizes, and a Guggenheim Fellowship, among almost twenty other awards and distinctions.

But it hasn’t been an easy glide to the top of Mount Parnassus, and that is where the tenacity comes in. Oddly enough, he didn’t always have it.

The oldest of three siblings growing up in Boiling Springs, North Carolina, Rash did not start out as a promising student. Unless he was reading or roaming the woods around his grandmother’s house near Boone, he found it difficult to focus. (“I’m the least well-rounded person,” he says. “If I’m not interested in something, I can’t fake it.”) He failed the sixth grade, which, he notes dryly, “in North Carolina at that time was pretty hard to do.” He almost failed high school biology, too, preferring to spend his time in shop class.

At the same time, Rash knew how much his parents valued education. James and Sue Rash met in the early 1950s while working at a cotton mill in Chester, South Carolina, and both went back to school as adults—Rash’s father rode a bus all the way down to Columbia to take night classes—in order to give their children opportunities they never had. James went on to teach visual art at what is now Gardner-Webb University, inspiring Rash’s lifelong fascination with painters and painting (his middle name is Vincent, after Van Gogh).

When Rash was in high school, his father was hospitalized for depression, an illness that tormented him for years. Sue Rash was left alone to look after three children in a small Southern town, one that often felt to her eldest son like its own dwarf planet. But when the family needed support from their neighbors, they got it. “The whole town helped us,” Ron says. “It was a struggle that was never spoken of, but they knew. And people came through for us.”

Rash learned to center himself by running. Unlike baseball, which he played as a boy, or basketball, which he loved but never mastered, running was a solitary, meditative pursuit that honed a level of focus nothing else could touch. It required no equipment. He could do it anywhere. Most important, it was a sport made of rhythms: breaths, footsteps, heartbeats. Loops, laps, splits. The event he ultimately settled into, the eight hundred meters, is notoriously difficult; it’s too long for a sprint and too short for long-distance pacing. The gangly Rash seemed to have been born for it, and his skill as a runner soon earned him a scholarship to Brevard College. The more he ran, the more addicted he became to the rare moments when the training took over and he floated free of himself, feeling stronger and faster than he’d ever been.

When he wasn’t in school or at the track, Rash escaped to the mountains of Watauga County, where his uncles taught him to hunt and fish and bale hay on their neighbor’s farm. He also began reading more intensely, beyond his boyhood favorites of Jack London and Mark Twain or the eerie shadowlands of Edgar Allan Poe. At fourteen, he discovered Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment, the first book that truly shook something loose inside him. During the famous scene in which the young Raskolnikov murders the pawnbroker, Rash felt utterly transported, almost possessed. “I had always entered the book,” he says, “but it felt like that book entered me.”

Rash didn’t attempt any serious writing of his own until he was an undergraduate English major at Gardner-Webb, where he transferred after a year at Brevard. Encouraged by an attentive professor, he drafted his first short story, “Turtle Meat,” about a man who used a snapping turtle to find the corpses of people who had drowned. The story won a fifty-dollar prize in a county writing contest, which inspired him to write more stories and try new forms. He fell in love with the rhythmic freedom of poetry, “the sounds of words rubbing together,” especially the work of Seamus Heaney and Dylan Thomas (who, Rash points out, was also a runner). Language could do so much more than simply convey information; it could reach inside of you the way a Doc Watson or an Earl Scruggs record could, strumming “three chords and the truth.” Poetry was music, and that music held him tight.

Rash’s first poem took him into deeper, more personal waters. It recalled an afternoon of fishing with his uncle Earl, a hard drinker with a wild past who once put on a football helmet and wrestled an orangutan at the county fair. Earl was patient and kind with his young nephew, eager to teach him how to read the land while stressing the value of hard work. He embodied many of the qualities found in Rash’s resilient blue-collar characters, who are sometimes faced with impossible choices—what Edith Wharton once called “the hard considerations of the poor”—but whose fundamental decency isn’t predicated on perfection. When Rash speaks of Earl now, the words catch in his throat. “I just wanted to give him something,” Rash says of the poem, which he lost years ago. “The people who stood by me have made what I do possible.”

Rash continued to write while pursuing his master’s in English at Clemson University and devouring much of the Western canon, from Beowulf to James Joyce, William Faulkner, and Eudora Welty. He favored authors who used the culture and customs of a single place (be it the real Dublin, Ireland, or the “apocryphal” Yoknapatawpha County, Mississippi) to express the universal. He likens this to drilling for water: The bit enters the earth at one small point, but it is searching for a large, flowing current. The writers who fail to do that, who perpetuate old tropes and play up the exotic for its own sake, are doomed to languish in the bargain basement he calls “regional color.” In the best of Southern literature Rash found voices who endured not because their worlds were narrow—he still cringes at the stereotype of the “unlettered country genius”—but because they were vast: Faulkner read Dickens and Balzac, Welty drew from Mann and Yeats. Storytelling was an act of inspired cross-pollination. And in capable, compassionate hands, the South became a window, not a cage.

Photo: Daniel Dent

Rash gets inspiration from the outdoors, and often hikes and fishes in the mountains.

Rash’s time at Clemson changed his life in two distinct and divergent ways. The first involved a chance meeting with a fellow student in the master’s program, Ann Todd. Standing only five foot two, Ann sat on a dictionary when she typed, and Rash needled her by asking if she was trying to learn new words by osmosis. (“A lot of people would not have thought that was funny,” Rash says, “but she did.”) Six years later, the two were married, and soon had a daughter, Caroline, and a son, James.

The second event was a workshop held by a Famous Writer whom Rash greatly admired at the time, but whose name he’d rather not disclose. Rash signed up for the afternoon session hoping for guidance on a short story he knew didn’t yet work. Instead of offering that guidance, the Famous Writer eviscerated Rash in front of his friends and teachers, taking great pains to chart every grim coordinate of the story’s awfulness. Red-faced, the humiliated Rash returned to his shared office and sat alone in the dark, staring at the walls. After fifteen minutes of gazing into the abyss, Rash summoned up the “weird little knot of confidence” that always tightened when someone wrote him off. “Okay,” he told himself. “This is the way it’s gonna be. There’ll be people that do this. It’ll probably happen again, so are you gonna let this stop you? Or are you gonna become better?”

The sting of that rebuke hasn’t entirely disappeared, even decades later, but Rash now believes the writer did him a favor. Until then, he hadn’t realized just how serious he was about his writing and how hard he was willing to work to improve it, regardless of who liked it—or didn’t.

Rash moved forward, revising his work regularly, but not religiously, after he and Ann were married. Sometimes, though, there simply wasn’t enough time to focus on creative projects; the list of his responsibilities as a husband, father, teacher, and friend edged them out. Much as he regretted that, he accepted it as inevitable.

That changed in 1980, when Rash’s father died at the age of fifty-six. Rash was then twenty-eight, and the sudden loss triggered a radical reappraisal of his priorities. Do I really want to live my life, he thought, not knowing if I could do this, if I could be a writer? Committing to that path would mean training for it: stripping his life down to its barest elements and getting rid of anything that did not involve his wife, his kids, or his job. It would also mean staring down years of potential failure and disappointment. But time, he realized, was not an infinitely renewable resource. He would rather try and fail than never know.

For almost twenty years afterward, Rash wrote almost every day with no assurance that anyone would ever read his work. He woke early in the morning and wrote before teaching a full load of classes, first at a local high school, then at a technical college. He didn’t socialize, didn’t travel. When his young children wanted to go to the park, he wrote on the picnic table at the playground. He wrote on weekends, he wrote on holidays. It was not uncommon for him to take a piece through fifteen drafts—or more—before finally sending it off to a magazine or literary journal.

Rash worked in all forms, using poetry to experiment with rhythms while distilling his prose into taut, muscular portraits of mountain life. In both, he started with a visual image (a farmer standing in a field, for example, or a fish dying in a stream), then wrote toward it, chipping away at a draft’s wall of words until that image came to life. Again and again, he returned to the places that haunted him, such as the Jocassee Valley in upstate South Carolina, which was flooded for hydroelectric power in the early 1970s, and the Shelton Laurel Valley in Western North Carolina, where Confederate soldiers executed thirteen Union sympathizers in 1863.

Every poem, every story, was an attempt to honor the beautiful, troubled, often contradictory and violent world of Southern Appalachia without blurring its edges. As his close friend, the novelist Steve Yarbrough, puts it, “Ron’s determination as a fiction writer seems to be: never, ever to call attention to Ron Rash, and to keep the focus always on the lives of the characters. He knows the area he writes about inside and out. You can feel the love he has for the landscape, and for the people who inhabit the landscape.” At times Rash’s understanding of those characters required a careful alchemy of research and something just shy of Method acting. He pored over history books and interviewed old-timers, but the breakthroughs came from hands-on experience. He once sat in a forest for hours, inspecting trees, to figure out how his protagonist would hide a body. To grasp the physical sensations of drowning, he held his breath at the bottom of a pool.

Having amassed a stack of rejections by the mid-1990s, Rash cherished every triumph, and soon he’d accumulated enough of them to publish three collections of poetry and short stories with small presses. Eager to learn from fellow craftsmen, he nurtured friendships with writers he esteemed, such as William Gay, Lee Smith, Robert Morgan, and George Singleton. Still, he struggled to find a larger audience, and he wasn’t quite sure how, or if, he could paint on a larger canvas. He threw away two finished novels that he felt were too forced, too plotted, too deadened by the top-down mandates of an outline. He did not publish his first novel, One Foot in Eden, until 2002. He was forty-nine.

Were the narrative of Rash’s life split into three tidy acts, the success of his first novel after such a long, hard-won apprenticeship would mark the satisfying conclusion. Except that it wasn’t. Despite getting a flurry of positive reviews and winning three literary prizes, the book didn’t sell the way the publisher hoped, and neither did his next one, Saints at the River (2004), which won three more prizes, or the third, The World Made Straight (2006). All three novels explored the ways in which rural Appalachia has been both shaped and destroyed by people at war with the land, and in some cases, at war with one another: the flooding of mountain valleys, the battle over wild rivers, the slow creep of the drug economy into desperate communities. The conflict between humans and their environment is not a regional concern, and these were not “Southern” stories; they were, and are, American stories that happened to occur in the South. But, unfortunately for Rash and many other artists, the rest of the country doesn’t always see it that way.

Photo: Daniel Dent

Rash at work.

In 2007, Rash finished his fourth and most ambitious novel, a dark, sweeping Shakespearean epic set in a North Carolina logging camp during the Great Depression. Nearly a dozen publishers passed on it before the manuscript finally landed with Lee Boudreaux at Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins. Boudreaux was floored by the novel’s brilliant female villain, Serena, who sends a swarm of loggers gnawing across the Smoky Mountains like carpenter ants just as Horace Kephart is campaigning for a national park. The story’s chorus of minor characters gave it the depth and ballast of a Renaissance play, with the loggers caught between feeding their families and gutting the land that supports them. “It was propulsive,” Boudreaux recalls of the book, which struck her as both timeless and timely, a fiery critique of capitalism run amok. She recognized the strong voices of the rural South she remembered from growing up in the Northern Neck of Virginia, and she saw parallels to the environmental clashes in other parts of the country, like the Pacific Northwest. “You’re so vividly in the landscape with every word Ron uses about the land and with every piece of dialogue,” she says. “You feel like these people have sprung to life in front of you.”

Championed by the independent booksellers Rash had befriended, Serena went on to become a New York Times best seller and a finalist for the 2009 PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction before being made into a 2014 film starring Bradley Cooper and Jennifer Lawrence. It also renewed interest in Rash’s earlier work, with The World Made Straight adapted for the screen in 2015. Around the same time, Rash received numerous prizes for his short fiction, published his first story in the New Yorker, and won a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2017.

Rash and Boudreaux worked on two more books before she left HarperCollins, and then reunited for his new book published by Doubleday. “What I love about Lee,” he says, “is that she pulls no punches. That’s what you want in an editor.” That bedrock of trust was critical when Rash began drafting In the Valley. He had been nagged for years by the feeling that several of the characters in Serena had more to tell him, but he had no desire to write a novel-length sequel. (“That’s too much like Ghostbusters part two,” he says.) He set out to work in a new form, the novella, and bring forward the voices of the loggers, specifically the character of Ross. After reading the manuscript, Boudreaux felt Rash had lingered too long on one of the female leads and encouraged him to focus on the “spooky” scenes he had written of the loggers hauling timber out of the fog. For the next pass, he’d added brief, lyrical interludes, told from the perspective of the animals fleeing the valley as it was logged, which widened the story’s aperture into the unearthly realm of biblical metaphor. With that small flourish, all the elements clicked into place. “Ron’s got the willingness to sound those deep bass notes,” Boudreaux says, “and play those chords that unsettle you in your bones.”

Does a swell of praise change a person’s life? Of course it does, in some ways. Rash gets more requests for readings and interviews, and he’s learned how to write in hotel rooms while on book tours. More exciting: He can now travel abroad. In France, Ireland, Australia, the Netherlands, and New Zealand, he’s found enthusiastic readers who have never visited Appalachia but see themselves and their families in his work. He is humbled by and grateful for that, having spent so many years searching for that universal current. “He will never take any of it for granted,” Steve Yarbrough says. “He wouldn’t even know how.”

Almost everything else has stayed the same: the morning workouts, the reading, the unsweetened tea. The long walks in the woods, scanning for snakes. Now at work on his twenty-third book, another novel, Rash plans to keep it that way. He’s spent too much of his life leaning over yellow legal pads, batting away distractions, to worry about the demands of literary fame. He’d rather keep reading, keep writing, keep sweating it out every day. Better to focus on the page in front of him, on chasing transcendence over the horizon.

This article appears in the August/September 2020 issue of Garden & Gun. Start your subscription here or give a gift subscription here.