Food & Drink

Southern Masters: Frank Stitt

To understand the genius of the godfather of Southern cuisine, you need to spend a day in the kitchen with him

Photo: William Hereford

“The good cook, like the good jockey, must have a clock in his head.” —A.J. Liebling

10:00 a.m.

Guadalupe Castillio has already been in the kitchen at Highlands Bar and Grill, in Birmingham, Alabama, for two hours, cleaning by hand each of the five hundred crab claws he will serve that evening from the oyster bar. He is also in charge of checking the quality of the deliveries coming in a steady stream to the restaurant’s back door—local farm eggs and vegetables, seafood from the Gulf Coast, freshly baked breads—and he has just admitted a large order of chives, chard, and baby lettuces harvested earlier that morning by a local supplier. The first pleasant kitchen job of many today for Highlands owner and executive chef Frank Stitt is to handle, smell, and taste these still-wet-with-dew greens.

Outside the walk-in refrigerator are trays of fat, precisely ripe strawberries. “Picked this morning on a farm near Cullman,” Stitt says, handing me one. Not much of a strawberry fan, I could be made one by these: The berry is a little flash of sweet neon on the palate.

Highlands chef de cuisine Zack Redes hands Stitt a menu from the night before, with handwritten numbers beside each appetizer and main course indicating how many times someone ordered it. Greg Abrams Black Grouper with Marinated Crawfish tops the list at thirty-seven. Then the two chefs discuss the menu for tonight: the merits of blueberries in a fish sauce; pairing batter-dipped onion rings with the rib eye. The kitchen is already filling in around them with staff, though Highlands—the flagship of Frank Stitt’s four-restaurant fleet—will not open for business for seven more hours. A few of these people have worked here since Stitt opened the restaurant, thirty years ago. Not one of them—now tying on their aprons and snugging down their Highlands caps—looks anything less than thrilled to be here now.

At 10:30, Stitt walks next door to Chez Fonfon, his tone-perfect riff on a French bistro. Housed with Highlands in a 1925 Spanish-style building on a leafy street in Birmingham’s party-down neighborhood of Five Points South, Fonfon is the youngest of Stitt’s restaurants (opened in 2000) and, with sixty seats, the smallest. With its art deco detailing and French lithographs; its rustic wood tables and leather banquettes; its cheese and dessert table and wall of wines, velvet drapes, and tall windows fronting the street; and its white marble bar and rose-arbored dining patio out back with a boules court, it is also his most charming. The place feels airlifted from Montparnasse.

A half dozen men and women servers, dressed in white shirts and aprons and black vests, sit at the bar being briefed on the specials and fish dishes du jour by Adam Grusin, the chef de cuisine here. The mood among them is scholarly; most take notes. During the week Fonfon serves meals from 11:00 a.m. until 10:00 at night from a menu featuring classic bistro dishes such as moules et frites, escargot, country pâté, and frog legs. Accompanying this menu is a much celebrated wine list, and Grusin is followed by Gray Maddox, Fonfon’s sommelier, who goes over with the servers the virtues of a new Saint-Bris white, a new Côtes du Rhône rosé…

The meeting is over precisely at 11:00. At 11:01 the first eaters walk in and are seated at a sun-dappled table by the window. Stitt and I watch them from the bar as they are handed menus, on their faces an expression of delighted expectancy that I will see on hundreds of other faces today.

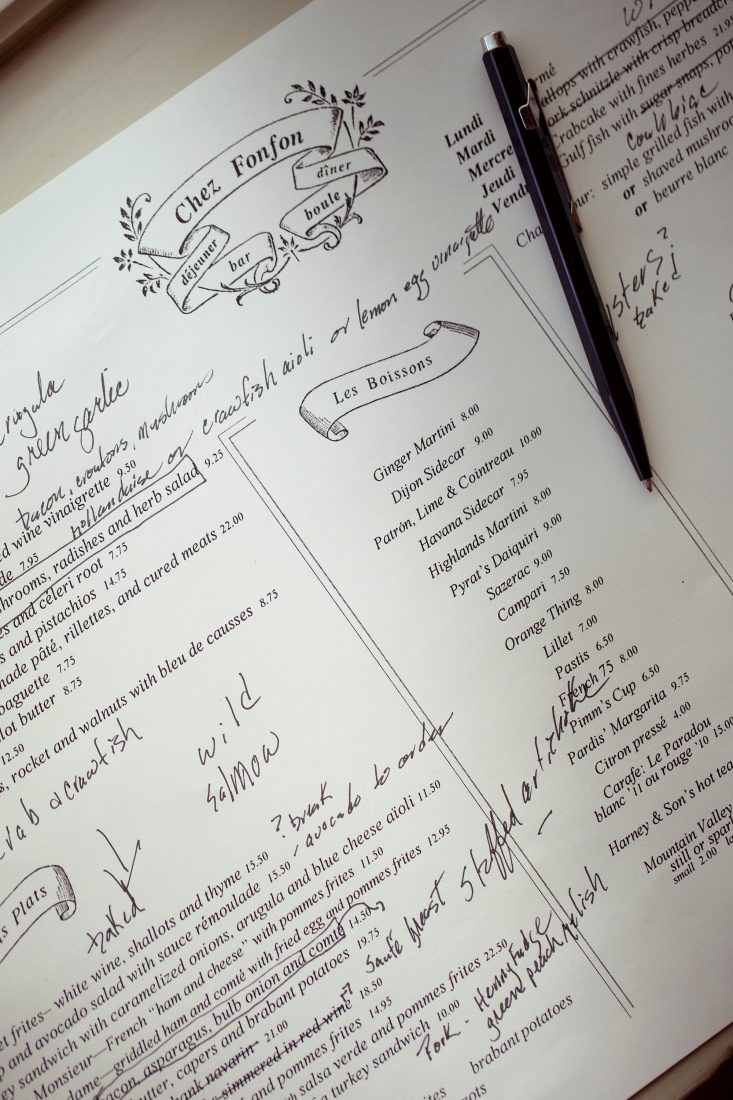

Photo: William Hereford

Notes on the menu from Chez Fonfon.

11:45 a.m.

After a visit to his cookbook-crowded office above Highlands to check e-mails and counsel with his assistant, Nikki Hallmark, Stitt drives about a mile to the elegant white limestone 1920s Beaux Arts building that contains his other two restaurants—Bottega, which he opened in 1988, and Bottega Café (1990).

On the Café side, the four cooks working the open kitchen and big wood-fired brick oven are “in the weeds”—literally covered up in order tickets. Moving around each other with choreographed celerity, to shouts of “One minute out!” and “Plating!” they ladle a fennel sausage pizza into the brick oven, tong a pork loin chop onto a bed of polenta.

Stitt stands at the “pass,” the counter where waiters pick up finished plates, talking to the café’s chef de cuisine, Scott Cohen, about the day’s menu and inspecting each order as it comes out. The trattoria-style Café is one of Birmingham’s most popular hangouts, and every table is full both in the dining room and on the outside patio.

Next door is Bottega, which Mario Batali has called “one of the best Italian restaurants outside of Italy.” It is open only for dinner, so the refined, walnut-paneled dining room is empty, but the kitchen is bustling with eight or nine people prepping for the evening under the supervision of chef de cuisine John Rolen. A sous-chef trims fresh redfish fillets. Another watches over a tall pot of octopus simmering in a stock of dried and fresh peppers, fennel, onion, thyme, coriander, and…three wine corks? “They say it helps tenderize the octopus,” says Rolen with a shrug. Later this octopus will be grilled, sliced over a porchetta di testa of pork head meat that takes two days to prepare, and served with fava beans and pea shoots. I have a taste of it that night: It is a dish to make you want to fall down on your knees and thank God you have a tongue.

At one o’clock, Pardis Stitt breezes glamorously into Bottega. She is Frank’s wife and partner in the restaurants, the successes of which (Frank is the first to tell you) are due as much to her as to him. Pardis and Frank sit down at a table in the empty Bottega dining room with Cohen and one of his sous-chefs to discuss the late spring changes to the Café’s menu. From the head of the table, Pardis runs this meeting and a later one today with charm and authority, while Frank sits very straight in his chair, listening mostly, wrapped in his serene, gracious, slightly old-world patrician aura.

“Frank wants to take the chicken paillard off the menu,” Pardis says, leaning in toward the others, her black eyebrows raised. “Are we all okay with that?” After a pause, everyone nods. “Why?” I can’t help but ask. “It has lost some momentum,” Frank says. “We’ve had it a long time. But chances are it will be back on in a couple of months. You have to be very careful taking things off the menu. I’ve had people cuss me out in the hallway over a dropped chicken Caesar salad.”

The meeting ends at 1:45, and Frank takes me back into the still-crowded Café and sets me up at the big L-shaped bar. “Order whatever you want,” he says. “I have to go home and let the dog out.” His eyes are on the servers, who glide between tables with intent aplomb, like sharks on a flat. “Pardis and I coach them on how to carry themselves,” he says approvingly. “We tell them, ‘Think of yourselves as a ballerina or a matador.’”

While Frank is gone, I allow myself a modest working lunch of seared beef carpaccio on a bed of arugula with sliced Parmesan, and grilled jumbo asparagus with farm eggs and more sliced Parmesan. On the salmon-colored wall above the bar is a mural of happy, well-fed cherubs tooting horns. I know exactly how they feel.

The Godfather of Southern Cuisine was born in 1954 in the North Alabama town of Cullman, where his father was a surgeon and his mother one of the best cooks in town. Her parents owned a farm with Jersey cows, chickens, a large vegetable garden, and strawberry and asparagus patches where Frank developed early a taste for what he calls “the almost spiritual experience” of eating fresh, farm-raised foods.

After a couple of years at Tufts University, he transferred to the University of California at Berkeley to study philosophy, which he might be teaching today had he not discovered Alice Waters and her groundbreaking Berkeley restaurant, Chez Panisse. The pure joie de vivre of the way she and her associate Jeremiah Tower approached cooking and eating caused Frank to substitute the revolutionary food writing of Richard Olney and Elizabeth David for Spinoza and Kant. He worked part-time for a while at Chez Panisse, and for a speed-skiing Swiss chef in San Francisco. Then, in 1977, a few months before he was supposed to graduate and armed only with a letter of introduction to Olney from Alice Waters, he flew to London and was hired as an assistant to Olney and Tower, who were there creating the Time-Life cookbooks.

What followed that was a dream year of sine qua non education for a chef: serving as Olney’s personal assistant in the South of France; working with wine tasters in Bordeaux, and with Simca Beck, Julia Child’s partner, on a French rose farm; a stint in Paris; a few months of living and studying Italian cooking in Florence. By the end of that year, Frank knew he wanted to come back to the United States and open his own restaurant. He could easily have done so in San Francisco, New York, or New Orleans, but he made a far more surprising and risky choice: to go home to Alabama and locate his restaurant in Birmingham.

Birmingham in 1980, when Frank went back there to live, was a fine-dining desert. I know because I was there. What Frank calls his “Alabama epiphany” was realizing that the city was ready for something other than country club food, barbecue, and catfish. And he knew exactly what he wanted that something to be: a comfortable, unpretentious restaurant, anchored in Alice Waters’s farm-to-table ethic, with impeccable service and unfussy food that married all he had learned of French techniques and traditions to the Southern cooking and ingredients he had grown up with. A restaurant of “integrity, style, and substance,” but one with a merry, gregarious, even risqué, bar scene. Ergo, Highlands Bar and Grill.

Photo: William Hereford

Ready to Serve

Stitt checks in with diners at Highlands.

From the day it opened in 1982, Frank says, “it took off like a rocket.” In 1984 Esquire named it one of the Best New Restaurants in America, and later inducted it into that magazine’s Restaurant Hall of Fame. It has been on the short list for the James Beard best restaurant in America award for five years in a row. In 2001, Frank won the Beard Award for best chef in the Southeast, and he was nominated for national outstanding chef in 2008.

But more significant than those and the many other awards Frank and his restaurants have garnered is the truly monumental influence he and they have had on food and food thought throughout the Southeast. Around a dozen young chefs who were trained in one of Frank’s kitchens have started successful restaurants of their own that bear his style and food philosophy. Major culinary talents such as Mike Lata and Sean Brock of Charleston, South Carolina, and Hugh Acheson of Athens and Atlanta acknowledge large inspirational debts to Frank, and in March, at the Charleston Wine and Food Festival, a group of those chefs presented him with the first annual Frank Stitt National Chef Award for his contribution to Southern cuisine.

The day after the one I spend with him in his restaurants, Frank took me out to his farm, southeast of Birmingham. Called Paradise Farm, the place is well named: a comfortable farmhouse, a barn holding his five polo ponies (“a totally impractical thing,” he calls his twenty-year love of polo, “but it’s an addiction”), more than a hundred laying hens that supply his restaurants with eggs, and twenty six-by-twenty-foot raised beds and a greenhouse that provide them year-round with vegetables and greens.

While Frank drove me and his blue heeler, Fernando, around the property on a four-wheel-drive Mule—past a pond, fenced paddocks, a stream off which we jumped a pair of wood ducks—I asked him how he accounts for the majestic and seminal success of his restaurants over such a long time.

The Godfather thought for a minute, then said, “Mostly it’s just keeping the blinders on—really focusing on what we’re doing and what we’re after, and never being a hundred percent satisfied. I also think it’s important to know more than the other guy does, to be more curious, to study more about technique and ingredients and the traditions and cultures of food.”

He might well have added this: working ten to twelve hours a day at his restaurants, most of it on his feet. Six days a week.

Photo: William Hereford

The charcuterie plate.

3:30 p.m.

After a meeting in Bottega’s dining room with the eight managers of the restaurants (at which Pardis directs them to communicate to the servers her strong desire that they use some part of their bodies other than their feet to open the kitchen door when they are carrying dishes), and after a return to Highlands (which will open its doors to a ravening horde of eaters in less than two hours now), Frank is unhappy with an onion marmalade planned to accompany an ethereal (I ate one) appetizer of seared foie gras atop a buckwheat pancake.

I had asked him if he still cooks in the restaurants. The answer is mainly no, but the following sort of offhand display of brilliance is what he does do. He dices one of the aforementioned strawberries along with a few leaves of mint, then scrapes that mixture into a bowl to which he adds pinches of salt and pepper, splashes of olive oil and cider vinegar, and a bit of lemon zest. He stirs it, tastes it…grins, and passes it to Zack Redes and me to taste: Pulled from the air in less than a minute, it is simply a perfect concoction of flavors for the foie gras.

We move between the eleven people now working the kitchen to a sous-chef making pork crepinettes studded with chard and shallots that will be seared, covered with a net of caul fat, roasted, and served with fried oysters and a lemon aioli. (Heaven its ownself! I also ate one of these.) Then to another guy filleting a twenty-pound cobia that was speargunned neatly between the eyes by a supplier on the Gulf Coast who believes they taste better when harvested that way.

Photo: William Hereford

Addressing the staff at Highlands before the evening rush.

At 4:00, we walk next door to Fonfon to check on the triggerfish and frog legs, and to attend with Gray Maddox a tasting of wines being offered for consideration by a local distributor. The consensus: A Loire muscadet is bigger than most with a great nose; four Grüner Veltliners are so-so, and one sings. Frank thinks the Côtes du Rhône Grenache has too much cassis taste to it. I am not spitting my sips into metal cups as the others are, so I really don’t remember how anyone felt about the Malbec or the two Arbois.

5:00 p.m.

Following a menu briefing at highlands with its servers, Redes, and its stalwart general manager, David Parker, Frank goes home for an hour to let his dog out again. This time I am set up at the Highlands bar, where Guadalupe Castillio, now at his evening job of oyster shucking, seems to divine that I am wearing a little thin and kindly offers to fortify me with a dozen giant Apalachicolas and an order of the crab claws he had cleaned that morning. I am talked into it; and, by an equally solicitous bartender, into a glass or two of Sancerre. As happy to be off my feet as with this repast, surrounded by the chattering, well-dressed bar regulars who gather here at Highlands every night like elephants at the Mushara watering hole, I feel welling up in me the impossible-to-restrain, bright-hearted bonhomie that Highlands engenders. The room fairly buzzes with laughter, expensive brio, and mingling hormones: just exactly, I imagine, what Frank had in mind.

Ernest Hemingway had his clean, well-lighted places. That nonpareil eater and commentator on eating A. J. Liebling had his Restaurant des Beaux-Arts on the Rue Bonaparte. And by the grace of God, my hometown has Frank Stitt’s four restaurants. After a while, as I followed Frank around in those restaurants until 9:00 p.m.—watching splendid food being prepared and delivered by servers moving like matadors to diners as delighted as horn-tooting cherubs—they all seemed to blend together into one, and I had this intimation: that all great food is the same happy place. At his farm, I asked Frank what he thought of that.

“Yes!” he said. “That’s what we’re all after—a place that makes people feel good, that gives them a respite from all the horrors of the world with the happiness and comfort of good food. That’s the Holy Grail.”