Southern Masters

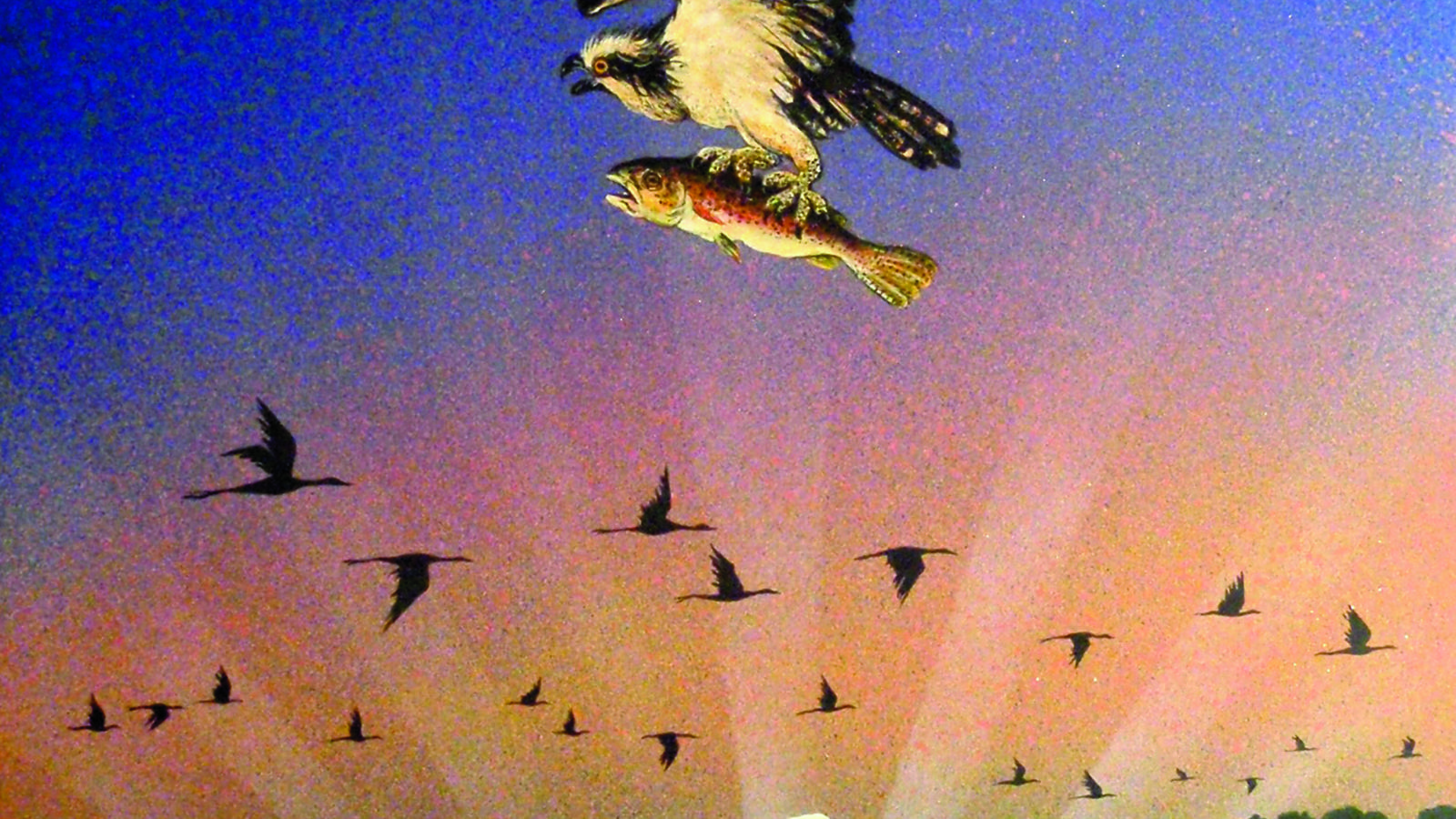

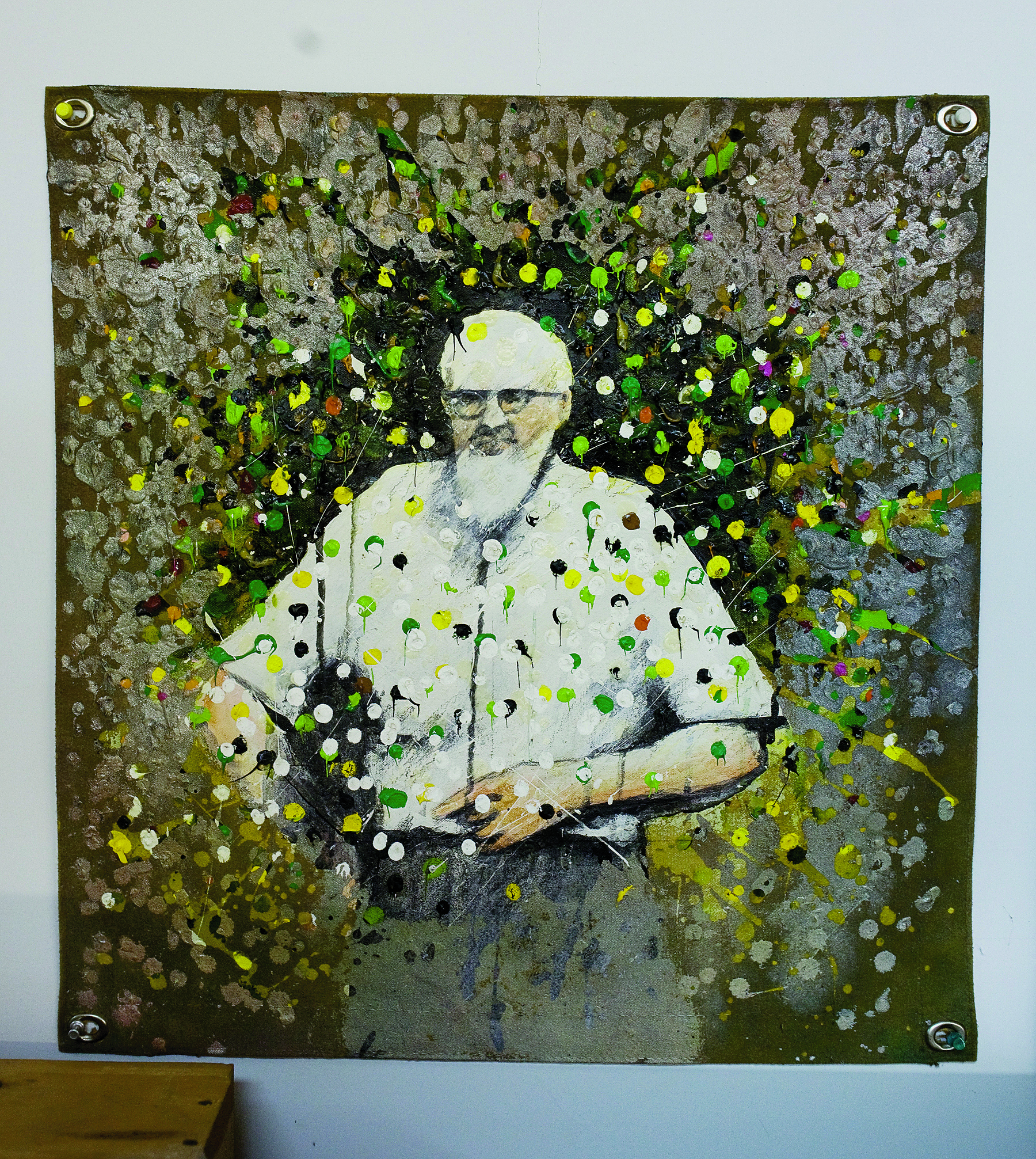

The Art Ambassador

William Dunlap is bold, outspoken, and not afraid to have a good time

Photo: Caleb Chancey

The artist in his Mississippi studio with more than a few things that inspire him

On January 20, 2005, the date of George W. Bush’s second inaugural, I spent the day in our nation’s capital in the unlikely company of my friend the artist William Dunlap, who lives in nearby McLean, Virginia, for half the year. I knew Dunlap had not cast his vote for Bush—to this day he persists in sharing his irritating opinion that Al Gore was a bad candidate who would have made a good president. But he is a Southerner, with a Southerner’s sense of history, and he is capable of rising, with great style, to almost any occasion. So it was that immediately after the swearing-in, we made our way to the balconied Pennsylvania Avenue apartment of the late conservative columnist Robert Novak to watch the parade. As soon as we hit the door, Dunlap spotted a tall brunette who was very good-looking—but also sporting an insanely unflattering hairdo of sparsely spaced, gel-induced spikes. Before I knew what was happening, Bill had marched straight up to her: “Baby, who did that to you? Tell me right now so I can whip his ass.”

I held my breath—I knew this woman, and she’s pretty formidable. Also, her husband was within earshot. But I should have known better. Within minutes, she was utterly charmed and they were the best of pals, laughing and talking about art and shared friends in the Virginia hunt country. Before it was over, she’d enlisted his help with a fund-raiser, and I’d swear he sold her a painting.

I have told this story many times because everything about that day tells you a lot about Dunlap. He’s an unreconstructed lefty but would not dream of missing something as significant as a Presidential inaugural or as potentially fun as a parade-watching party because of something as trivial as politics. He can charm unlikely women and disarm angry cops in riot gear with equal aplomb. This was the first inaugural after 9/11, after all, but Dunlap managed to fast-talk us past the endless barricades my press pass was powerless to get us through. Then there was the lunch he’d hosted the day before at the Cosmos Club, where his guests included Mississippi Republican Senator Thad Cochran and Marsha Barbour, the wife of the Republican governor.

Photo: Caleb Chancey

A bronze sculpture Dunlap cast for the Governor’s Arts Awards

But that’s the thing about Dunlap. He’s an extraordinary painter, but he’s also a fully engaged citizen of the world. When I remark on that, he shoots back, “Well, thank you, but isn’t that why we’re here?” adding that in any case, the “difficult, more precious” approach to his craft has never held much interest. “I want to live a good, interesting, compelling life and not suffer. I think artists and writers are cast in this role. It’s a post-Christian thing—Jesus died for our sins and so must James Joyce. That may be why I don’t have a lot of artist friends. They whine and complain. I have to lecture them. I say, ‘Listen, our job as artists is to have more fun than anyone else.’”

Throughout his life, he’s always managed to excel at that. But fun has always been entwined with the pursuit of his art. Between college and grad school in his native Mississippi, he toured the country with a rhythm and blues band, playing drums, but also soaking up the contents of the museums in each city. While teaching at Appalachian State University in the 1970s, he convinced the dean to let him start a branch campus in New York, and he and his students commuted to an enormous loft he rented in Tribeca. In 1995, he won a Wallace Grant and traveled and painted in Southeast Asia for six months. Ten years later he returned to Thailand with his wife, Linda Burgess, and their fourteen-year-old daughter, Maggie (both of whom are artists), for a month-long painting holiday, and last fall the trio spent a month as visiting artists at the American Academy in Rome.

He has produced work that resides in the collections of institutions ranging from the Metropolitan Museum and the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan to the Mississippi Museum of Art in Jackson and the William Morris Museum in Augusta, Georgia. But he has spent at least as much time serving as a roving ambassador of sorts, employing his famous charm and seemingly tireless energy to promote Southern art and culture from a variety of platforms including the Ogden Museum of Southern Art in New Orleans, where he serves on the board of directors, and the Governor’s Awards for Excellence in the Arts ceremony, which he emcees every year in Jackson. And while he excels at his official posts (he has elevated the Governor’s Awards to such a level of buzz and importance, you’d think it was Oscar night), his cheerleading goes well beyond any official duties.

“Bill’s generosity in supporting Southern artists of all shapes and forms is beyond measure,” says William Ferris, the folklorist and former National Endowment of the Humanities chair who now teaches at the University of North Carolina. Generosity is indeed a consistent theme. “Bill is a constant source of inspiration and encouragement to younger artists,” says David Houston, the chief curator and co-director of the Ogden. “He wants to bring the next generation along with his success.”

One member of that generation is Phillip McGuire, an artist who began his career as Dunlap’s assistant. “I realize now that Bill often took me along to meetings or art events where my presence was not really required,” he tells me. “I encountered writers, artists, and other cultural forces that I would never have had the opportunity to meet. I learned a lot from Bill. He affirmed that drawing is the underlying foundation of visual art, for example. Not least though is that he taught me how to be big-hearted, to freely give more than I’m asked.”

Among Dunlap’s closest friends is John Alexander, the artist originally from Beaumont, Texas, who now lives in New York. “The key to understanding Dunlap is realizing that what he does is not about self-promotion,” Alexander says. “He does it out of an enormous generosity of spirit. It’s real—and it’s not new.”Alexander points to one of their early experiences together, the Southern Rim Conference that Dunlap organized at Appalachian State in 1976, just after Jimmy Carter’s election. Taking as his rough model the Black Mountain Conference, which had included young artists of the 1950s (Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, John Cage) who later became superstars, Dunlap invited Southern artists, writers, and musicians to a four-day retreat in the Blue Ridge Mountains. “Southern art at that time was just beginning to get outside recognition,” Alexander says, “and Dunlap believed it would be in everybody’s best interest to bring all of us together so that we could share ideas and common goals.”

Photo: Caleb Chancey

A detail of a larger construction

In addition to Alexander, the attendees included artists James Surls, Jim Roche, and Ed McGowin, photographers William Eggleston and William Christenberry, and songwriter and artist Terry Allen—all of whom went on to become influential figures. But Dunlap’s particular genius was to include curators and museum directors and critics from outside the region as well. “He wanted to give them some understanding of what we do,” Alexander says. “It’s very difficult to explain why what we do is different—it’s almost like a mojo thing. The one thing we could impress upon them is our history of storytelling. It translates into pathos and a strong sense of narrative that comes out in all our work—and certainly in Dunlap’s. And they all got it. It is no exaggeration to say that everybody’s career took off after that. Marcia Tucker [then the curator of painting and sculpture at the Whitney Museum] gave Jim Roche a show, Surls had a show at the Guggenheim. Jane Livingston totally got it.” Livingston, then curator at D.C.’s Corcoran Gallery, would go on to commission one of Dunlap’s most significant works. But connections were by no means the only byproduct of the conference. “There had been an ‘us against the world’ mentality,” Alexander says. “And we left with a real sense of optimism. It was a huge deal.”

Not only does Dunlap continue to promote artists of the South in the wider world, he also promotes institutions within the region. He recently curated a critically acclaimed show of Civil War artifacts at the Ogden with his friend the Civil War historian and novelist Winston Groom, and he was instrumental in landing a huge plum for the museum in the form of Sally Mann’s recent show of photographs.

“I’m just trying to support the visual arts in a place where they’ve been fallow,” Dunlap tells me. “I’d like to think that the life I’m having, the career I’m having—other folks can have it too.”

The current world of engaged artists and enterprising museums was not the South in which Dunlap arrived. He was born in Webster County, Mississippi, to a schoolteacher mother and a father who died when he was three. His stepfather was a peripatetic Baptist preacher who moved the family all across the Deep South before returning to Mississippi when Dunlap was in high school, but he and his brother spent every summer with their grandparents in the small town of Mathiston. The family house, called Starnes House, is featured in some of Dunlap’s best-known paintings, as are the purebred Walker hounds his foxhunting grandfather raised. In the work, they become stand-ins for people, including the artist himself, and he still remembers their names: Lucky, Mary, Speck, Sally, and Bo. “Those dogs were all legs, lung, nose, and heart,” he says. “They lived to run.”

Photo: Caleb Chancey

A painting of Starnes House

After graduating from Mississippi College, Dunlap joined the Imperial Show Band, a stage band composed of white musicians and a black lead singer. In the first of many long road trips that still define Dunlap’s life and art, he traveled with the band across the country on Route 66, settling for a while in L.A., where he saw his first real art museum. “There was a great Jackson Pollock retrospective at the L.A. County Museum of Art, and seeing it was so different than seeing art on slides, which is pretty much all I’d ever seen in school. Until then, I had no sympathy with the whole action painting thing at all. I’d been trying to paint and draw like the Hudson River School as well as I could. But standing in front of a real Jackson Pollock, when it’s a huge field and fills your eye, I got it.”

His musical career ended when “the draft board got after my ass in a big way.” He headed home and “slid into” grad school at Ole Miss in the nick of time, and spent the next two years earning a Master of Fine Arts in printmaking and sculpture and running the campus foundry. It wasn’t until he was engaged in his subsequent teaching career in the 1970s, first at a junior college in Mississippi and then at Appalachian State, that he taught himself to paint. Astonishingly, he’d taken only formal classes in watercolor. One of his earliest works speaks to the process: a three-part Rembrandt portrait called Learn to Paint Like a Master in Three Easy Steps. The painting, he says, “dealt with the irony of being a twenty-seven-year-old kid just out of graduate school, suddenly finding himself a college professor. How absurd was that?”

At Appalachian State, in addition to the Southern Rim Conference, he exposed his students to speakers ranging from Tom Wolfe to James Dickey. And he introduced his friend Jane Livingston to more diverse aspects of Southern art. “Jane became the godmother of black folk art in America,” John Alexander says. “She put so many artists on the map, but it was Dunlap who exposed her to most of them. We had some of the great road trips of our lives, going to all these remote places to look at that stuff.”

Photo: Caleb Chancey

Broad Strokes

Dunlap with his painting Landscape and Variable: Indian Paint Brush (1987)

The road increasingly became Dunlap’s second home. In North Carolina, he lived on the edge of the Blue Ridge Parkway and constantly traveled back and forth between North Carolina and Mississippi and New York and Washington. In his paintings he captured the vistas from his windshield. “The landscapes that emerged offer a subtext of tension, of loneliness, of expectancy,” the writer Mary Lynn Kotz said at the time. “Faulkner’s themes are repeated by Dunlap—the land abides, surviving all of man’s attempts to cordon it off with boundary lines.”

Some of his best paintings from this period were exhibited in a show titled Off the Interstate, and one critic described him as the “chronicler of the Interstate Generation,” a description he doesn’t mind. “A lot of art comes from the side of the road,” he says.

The paintings reached their apogee in 1985 when Jane Livingston asked him to create a work for the classical rotunda of the Corcoran. His response was a contemporary cyclorama based on the cinematic Civil War battle panoramas he’d seen as a child. Called Panorama of the American Landscape, it is made up of fourteen canvases, each of which measures 68 by 94 feet, that encircle the viewer. “I made it about driving up Interstate 81, about that whole valley in Virginia and its history.” There are images of encroaching industrialization in the form of a cooling tower and factory, a Civil War statue at Antietam, dogs, of course, and deer heads, which are among the most powerful images in the piece. “The dogs are the hunters, and the deer heads are the hunted,” he says, explaining that he’d been on the first real hunting trip of his life just before he started the project, and shot a buck. He and his party roasted the backstraps, but the deer did more than feed them for the night. “When I got back, I found a sketch I’d made of three deer heads along with some drawings of Antietam, and I thought, ‘There it is.’ You’ve got the deer on one side, you gotta have the dogs on the other, and the whole thing just came together.” For six months he didn’t do anything but paint. “I had no social life,” he says. “But it was the most fun I’ve ever had in a studio.”

Photo: Caleb Chancey

Home Place

Starnes House in Mathiston, Mississippi, which Dunlap bought before it could be torn down by a developer

“Dunlap was ahead of the curve in making paintings that address history and place, often through multilayered images that engage the imagination of the viewer,” says David Houston. “It’s a strategy that is much like Dunlap himself—open, democratic, and participatory. It also encourages a dialogue that grows richer over time.”

The dialogue is especially encouraged in what Dunlap calls “those trippy things I do”: hybrids of paintings and sculpture that incorporate the found objects that fascinate him. Philip McGuire says that on his first day at work he was dispatched to the yard with a large Mason jar and instructions to fill it with the dried husks of locusts clinging to a giant oak. “For years they perched on a shelf in his studio in McLean like a jar of macabre preserves,” McGuire recalls. “Eventually they ended up in one of his assemblages.”

So do a lot of other things. “In one there’s a piece of linoleum that came out of my grandmother’s kitchen—that’s my version of Vitruvian Man,” Dunlap says. “All that stuff is charged in some way. I’m just trying to jog people’s memories.”

His own memory was jogged several years ago when he bought Starnes House to keep it from being bulldozed to make way for a Piggly Wiggly. He then moved an old Church of Christ onto the property to use as a studio. He probably spends ten days a year there, but the ground is literally fertile with inspiration. Among the first things he found in the dirt was a decaying leather dog collar with a brass nameplate bearing his grandfather’s name and five-digit phone number. Later, it showed up in an exhibition called Objects: Found and Fashioned—a show whose works also embody what William Ferris calls the artist’s “appreciation for the funky underbelly of the South, for worlds that both frighten and attract the uninitiated.”

Even with the more straight-ahead paintings, Dunlap sees himself as a symbolist—he’s even coined a term for his work of late, “hypothetical realism.” Though he first meant it tongue in cheek, “it is nevertheless fairly accurate,” he says. “These places I paint are not necessarily real, but they could be. It’s kind of like language in that everything stands in for something else. The dogs stand in for people, the places are generic but they’re specific. At a show in Boston, I heard someone say, ‘Oh, those are the White Mountains of New Hampshire.’ They were the Southern Appalachians, but it didn’t matter. He’d filled in the blanks.”

A painting he made for the chef Donald Link’s private dining restaurant, Calcasieu, is set in southwest Louisiana where Link’s family has a hunting camp, but he took a lot of liberties with the landscape. “You can’t stand anywhere on that property and see everything that’s in the painting. It’s really about the day.” He and Link drove from New Orleans to meet Link’s extended family. “They out-ate me, out-drank me, and there were all these dogs and children running around. And I saw one of the most powerful places on the planet through the eyes of a guy who grew up there. I don’t want to dis another part of the world, but I can’t imagine doing something like that in Ohio or Nevada or Utah.”

He did a similar commission for Eli Manning, who asked him to create a work incorporating a store near Philadelphia, Mississippi, that’s been in his mother’s family for generations. “I went and looked at it, and I visited with the family about it. I told Eli I couldn’t make the painting that was in his head, the painting of that exact place, but I could make it about the place. It’s all there—the storefront, the dogs running across the road—but I moved things around. It’s an implied narrative, and everybody else brings things to it.”

Photo: Caleb Chancey

The artist on the porch of Starnes, a place that has appeared in - and fueled - much of his work.

Last we talked, Dunlap was about to take one of his extended driving trips through the Delta, but despite his affinity for his home state, he doubts he’ll ever settle there. When he and his family are not in McLean, they are in Coral Gables, Florida, where Linda’s family lives. He says he likes the dual existence—and the distance from “home”—just fine.

“I love coming back. I want people from my gene pool, from my world, to see what I’m doing. That means more to me than you might think.” So does the debt he feels he owes to the place. “I don’t want to be bound by regionalism, I want it to be a launching pad,” he tells me. “The world is kind of wide open to me, and I’ve lived in it, and there’s something about growing up in the American South that has made that possible. You come out equipped with manners, and you know how to have a conversation.”

Fortunately for all of us, home and “home folks” are his favorite topics. Says Ferris: “In Faulkner’s Nobel Prize acceptance speech, when he speculates that at the end of time we’ll hear man’s ‘puny inexhaustible voice, still talking,’ I’m pretty sure he had in mind the voice of Dunlap, still talking about the American South and her artists.”