Sports

The Lone Star State’s Latest Football Phenom

In a state that produces the nation’s most elite high school quarterbacks, all eyes in Texas have been on Quinn Ewers. But the player with the trademark blond mullet and the rocket-launcher arm seems to be one of the few not buying into the hype

Photo: Fredrik Broden

Editor’s note: This story was published in the August/September issue of Garden & Gun, before Quinn Ewers announced he would forgo his senior season in high school and enroll early at Ohio State.

When Quinn Ewers was a young boy, he and his father, Curtis, would sometimes head up to the high school field in Pleasanton, Texas, to play football. “We had a lot of fun,” Curtis says. “I’d get down on my knees and we’d play tackle, and then we’d just throw the ball back and forth.”

One day, another father-son duo showed up to play catch. “My son wanted to be a quarterback, and I was going to teach him to throw,” says Ryan Smith, who lived in Pleasanton at the time. “I saw Curtis and Quinn out there. Quinn was slinging perfect spirals. As they were leaving, I asked Curtis how old his son was. He said, ‘Three.’ It was just ridiculous.”

Years later, after the Smith and Ewers families became friends, Smith told Curtis that after he and Quinn left the field that day, Smith turned to his son and asked, “Well, how do you feel about playing running back?”

It’s a cool and rainy spring day in North Texas, and Quinn Ewers has just arrived at an afternoon practice in the massive indoor football field at Southlake Carroll Senior High School in the Dallas–Fort Worth suburb of Southlake. Already today, he has logged a 6:45 a.m. weight-lifting session and analyzed game film with coaches and teammates, gone to school (virtually, due to the covid pandemic), studied for a final exam in his forensics class, and driven to Fort Worth for an hour-and-a-half postschool workout with the movement performance trainer Bobby Stroupe, who also happens to work with Kansas City Chiefs star quarterback Patrick Mahomes.

Ewers, a rising senior, is wearing sweatpants and a T-shirt adorned with a deer antler print for the thirty-minute practice, part of Southlake’s off-season program. He laces up his size thirteen Adidas cleats. And then the Southlake quarterback, who is the consensus number one high school football player in the country according to ESPN and the leading recruiting sites, Rivals and 247Sports, lopes his way out to the middle of the field.

He is impossible to miss. At six foot three and 210 pounds, Ewers is bigger than most of the linebackers practicing nearby, his musculature more “hoss thick” than sculpted. His hair, naturally brown, is bleached a frosty blond, a homemade job done by his mother, Kristen. The hair bleaching is a tradition on Southlake’s team, done every year during the playoffs to honor a towheaded former coach who died young. Ewers and a handful of other players have opted to keep it year-round, but it is his locks that stand out, thanks mainly to the cascading mullet that nearly touches his shoulders.

Fredrik Broden

Ewers fiddles with a football as he waits for the drills to begin, tossing it up in the air to himself, spinning it on his finger. And then he starts to throw to the wide receivers. His short, out-route passes are crisp and to the point. On his longer passes, the ball whistles with power. These passes, as a scout once noted, seem to defy the laws of physics and “accelerate as they progress…as if the second half of the throw had another gear” before they nestle into the chest of a receiver in the end zone, just under the banners that commemorate Southlake’s eight state championships and eight Texas high school players of the year. At one point, Ewers throws a deep pass so high that it thwangs off a steel beam on the facility’s ceiling, a feat that elicits oohs and aahs and one loud and distinct “Yeah, Quinn!” from his teammates.

A reporter and a videographer from Rivals follow Ewers’s every move during the practice. They’re here to do a story about where his college recruiting commitment stands at the moment. During their postpractice interview with him, Ewers clearly appears uncomfortable talking about himself, shifting his weight from one foot to the other, speaking softly and providing mostly short and direct answers to the questions. When it’s done, Ewers walks off the field, the last player to leave. “I don’t love doing interviews,” he tells me, and then smiles sheepishly, as if suddenly remembering that we have plans for an interview that evening. “I mean, they’re okay.”

Photo: Fredrik Broden

Ewers has been throwing a football with his father, Curtis, since he was a toddler.

Ewers has been described as the best high school quarterback prospect since Trevor Lawrence (the Clemson national champion and first pick of the 2021 NFL draft) and is only the second prep quarterback ever to achieve a perfect recruiting score (the other is the former University of Texas national champion and NFL Pro Bowler Vince Young). But despite that attention, the accolades, and the magnificent hair, the eighteen-year-old Ewers is, in many respects, a fairly typical American male teenager. The stubble on his cheeks and chin is an attempt at a beard he cannot yet fully grow. His preferred outfit is a pair of alligator cowboy boots, jeans, and a T-shirt. He drives a jacked-up Ford F-250—a former oil field truck. His father works in the oil and gas industry and has had a series of jobs mainly on the regulatory side. His mother teaches fourth grade in the Southlake public school system. Ewers has an older sister who is out of college and a younger one who is a promising volleyball player. In the summer, the family spends weekends at a reservoir west of Southlake, and Quinn water-skis, wakesurfs, and fishes. He does chores—makes his bed, folds laundry, takes out the trash, mows the lawn. He makes good grades, all As and Bs (his favorite class is history), and volunteers for Christmas drives for people in need. He mentors junior high kids—mostly, at this point, by high-fiving and tossing the ball with them rather than giving inspirational speeches. He has a long-term girlfriend named Hannah who was a Southlake cheerleader until she graduated this past spring.

Ewers is exceedingly shy in big crowds and in the company of strangers, often casting his brown eyes downward as he speaks. But when he’s with his tight circle of friends—a handful of teammates—he sheds his introversion. “Quinn is the one who makes us all laugh,” says Landon Samson, a wide receiver on the team who has known Ewers since fifth grade. “He’s kind of a goofball, to be honest.” Ewers and his friends play Rocket League on Xbox and poker for small sums of money. They go bowling and eat truckloads of Tex-Mex. They fish for largemouth bass and hunt, sometimes with their fathers, for deer and turkey and, once, for elk. They gather at Samson’s house to watch UFC matches. Nate Gall, a Southlake linebacker who has known Ewers since elementary school, has a Ping-Pong table at his house. The boys go there to play a version of the game called sting-pong, in which the winner gets to hit a Ping-Pong ball at the (shirtless) loser at close range. (They try very hard to avoid losing to Ewers.) The boys sometimes raise a little hell, as teenagers are wont to do, but are careful to never cross the line. “We just like to hang out and have fun,” Gall says.

And yet, because of his natural talent and the work he’s put into honing it, and because some very powerful men—the best coaches at the best football colleges, including Alabama, Ohio State, Georgia, LSU, Oklahoma, and Texas—have used all of their powers of persuasion to try to convince him to play for them, Ewers is, in another respect, almost wholly unique. He is, put plainly, one of the most prized commodities in a country obsessed with fame, rankings, and, of course, football.

Ewers was born at 8:00 a.m. on March 15, 2003, at San Antonio’s Methodist Hospital. Curtis and Kristen lived in the small town of Pleasanton at the time, outside the city. Curtis, who played quarterback in high school (“I handed the ball off a lot,” he says), noticed early on that his son was preternaturally adept at throwing a football. Quinn really could toss a spiral fifteen yards by age three, Curtis says, and that’s all he wanted to do. So the duo would head to the backyard or to the high school field nearly every day to throw. When it got dark, they went inside the house and kept going. Over the years, they smashed paintings, vases, and lamps. Quinn once zinged a ball through the cutout wall in the kitchen, just over Kristen’s head as she bent down to load the dishwasher. “I just gave in at one point,” Kristen says. “The house was meant to be lived in and I figured I’d hang my paintings back up when Quinn went to college.”

When Quinn was in second grade, his father took him to an informal quarterback camp run by Sonny Detmer, a legendary Texas high school coach and the father of the Heisman Trophy–winning quarterback Ty Detmer. “You just paid Sonny ten bucks a day and let your kid run around,” Curtis says. After the third day of camp, as Curtis remembers it, Sonny took him aside and told him, “Your kid is special.” Until that point, Curtis hadn’t thought too much about the way his son could throw a football. “It didn’t seem all that out of the ordinary to us,” he says. “But hearing that from Sonny, that planted a seed.”

Photo: Fredrik Broden

On Friday nights, fans fill the 12,600 seats of Dragon Stadium.

Football, of course, is the sport in Texas. The state has two NFL teams, the Dallas Cowboys and the Houston Texans, and numerous storied college programs, from Texas to Texas A&M to Texas Tech to Baylor, that have been led by legendary and innovative coaches such as Paul “Bear” Bryant, Darrell Royal, Mack Brown, and Mike Leach.

But high school football is the undisputed king, the common thread stitching together the fabric of some 1,400 communities across the state. And in the last decade or so, the needle on that thread has been quarterbacks. Thanks to year-round training—which includes the ubiquitous, offense-dominated 7-on-7 tournaments in the spring and summer—private quarterback coaching, and an early adoption of pass-heavy, no-huddle spread offenses, Texas high schools are now a hotbed of quarterbacking talent. (When asked if there is ever a day when he doesn’t throw a football, Ewers says he “sometimes takes a Sunday off.”) At one point in 2020, one-quarter of the starting quarterbacks in the NFL were Texas high school products, including Mahomes, Drew Brees, Matthew Stafford, and Kyler Murray.

In 2011, Curtis received a job offer at an oil-and-gas company in the Dallas–Fort Worth area. After looking around, he and Kristen found a town that was a great place to raise a family and an even better place to raise a quarterback.

What is now known as Southlake was once prairie, covered in native grasses and post and blackjack oak, roamed by buffalo and various Native American tribes. White settlers—mainly farmers—came to the area in the 1840s. The Lonesome Dove Baptist Church, which inspired the novelist Larry McMurtry, was among the area’s first public structures. After the completion of nearby Dallas–Fort Worth Airport in 1974, Southlake boomed, eventually becoming the fairly well-to-do commuter town of 33,000 it is today. Southlake is known for its excellent public school system, with its 100 percent high school graduation rate, but, above all, for its football team.

The Southlake Carroll Dragons began playing football in 1961, and started their ascent into the upper echelon of Texas high school football in the 1980s. From 2000 to 2006, under coach Todd Dodge, Southlake won four state championships and boasted an overall record of 98–11. Future college and NFL quarterbacks Chase Daniel and Greg McElroy played for Dodge during that run. In 2006, the team was quarterbacked by Dodge’s son, Riley, who became a local legend for a play during the 2006 state championship game, when he threw up on the field and then threw a touchdown pass and beat Westlake, which was led by the future Super Bowl–winning quarterback Nick Foles. In 2018, Riley became the head coach at Southlake.

The Southlake football team has a reputation for being overachievers, to some extent. It plays in 6A, the largest Texas high school classification, but with 2,500 students, the school is somewhere near the middle of the 6A pack when it comes to enrollment. The bigger schools usually have more and—aside from Ewers and a handful of others—often better athletes.

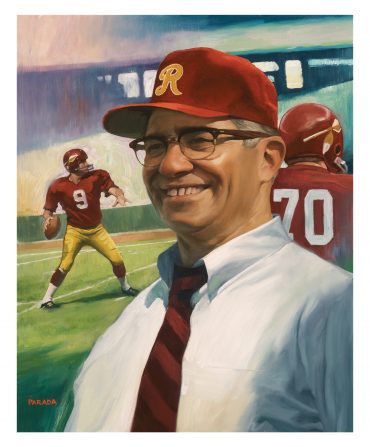

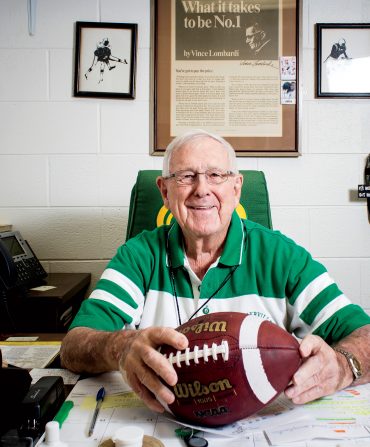

Photo: Fredrik Broden

Head coach Riley Dodge, in his office at Carroll Senior High School.

What separates Southlake, however, is that it has the only public school system of its size (or bigger) in Texas that is truly unified. All students—at the five elementary, two intermediate, two middle, and one junior high that all funnel into the senior high school—are Dragons. “There’s a lot of buying into that in town,” Riley Dodge says. “There’s a competitive nature built in, and by the time the kids are at the senior high school, they’re all on the same team.”

Though all the schoolkids—and, really, everyone in town—are Dragons, the varsity football players are the standard-bearers. Being a Dragon football player in Southlake is a rite of passage, full of pain and sacrifice: All players must endure the Dragon Maker, a preseason boot camp that includes weight lifting, sprints, and bucketloads of vomit. “It’s a test to figure out who really wants to be here,” Dodge says.

But being a Dragon is also about pride and responsibility. They are recognized all over town. Young kids wear replica jerseys of Southlake players, past and present, of Daniel, Dodge, and Ewers. A Dragon is the beneficiary of all who have come before him and must live up to that standard and pass it down intact. protect the tradition is the Southlake football slogan, seen all over school and in town, and it is loaded with meaning. On game days, Southlake shuts down and townspeople ascend a knoll to the 12,600-seat, $20 million (after renovations) Dragon Stadium. Tailgating, with RVs and tents, begins in the morning. In the stands, millionaires who live in the mansions that line North Peytonville Avenue sit, cheek by jowl, with folks who work in the town’s fast-food restaurants.

Most of the boys who play for Southlake will never again be able to top the jolt that comes from those Friday nights—the video scoreboard, the band, the collective exhortations of an entire town echoing out from under those stadium lights, into the shadows of that old prairie land.

For a few, though, those nights are only the beginning, a taste of what’s to come.

In 2011, the Ewers family rented a house in Southlake. Kristen began teaching. Curtis worked at his new job and coached Quinn’s peewee football team on the side, choosing his son as the quarterback. This was not necessarily an easy thing to do. “Every dad in Southlake thinks his son is going to be the next great quarterback,” says Luke Anderson, a family friend and former Dragon player. “It can get weird and competitive.” But Curtis navigated it well. The main reason: “It was 100 percent obvious that Quinn was the quarterback,” says Josh Spaeth, who played peewee with Ewers and is now a receiver and safety on the Southlake team. Curtis installed an up-tempo spread offense, a rarity at that level. Quinn thrived.

Unlike many high school quarterbacks in Texas, Ewers has never had a full-time quarterback coach. But he has occasionally enlisted the services of a few of them, including Joe McCulley, who was part of a group that trained quarterbacks for the family that owns the San Francisco 49ers. “Curtis wanted to put Quinn in my camp,” McCulley says. “Quinn was a fourth grader, so I was a little reluctant, worried about his attention span and ability to do the drills.” But after just one day in camp, McCulley was sold. “Quinn was focused and paid attention to detail,” he says. On that first day, McCulley asked Ewers how many laces were on a football. “Eight,” Ewers immediately answered. “I’ve had ninth graders who have to get a ball and start counting,” McCulley says.

Others soon began to notice Ewers, too. He received his first scholarship offer when he was in seventh grade, from North Texas. “I didn’t really know what it was,” he says. Ohio State, then coached by Urban Meyer, made an offer to him the following year. In all, he had nine offers before he even started a game at Southlake.

Riley Dodge had never seen Ewers throw when he took the head-coaching job at Southlake. When he finally did, he was duly impressed. “I think any random person off the street could see pretty quickly that he’s special,” Dodge says. “He has natural arm strength, his accuracy is off the charts, and he can make any throw on the field.”

But being a quarterback involves more than just throwing the ball. “He’s the heartbeat of the program, and we go only as far as he does, which is a great burden to carry,” Dodge says. “Quinn has worked hard off the field in the film room. He’s one of the tougher kids I’ve been around. He’s not a big social-media guy. And he’s got a quiet confidence, a swagger in a good way. He’s more comfortable in his skin than I am in mine.” While Dodge says that Ewers leads very well by example, he has encouraged him to overcome his shyness and become more vocal. “That’s not really my personality, but I’m working on it,” Ewers says. “I speak when I have to.”

In his freshman season, with a senior quarterback entrenched in the position, Ewers was the backup punter on the team. The next season, at age sixteen, he became the starting quarterback and completed 72 percent of his passes, throwing for 4,003 yards, forty-five touchdowns, and just three interceptions while leading Southlake to the state quarterfinals. And then the floodgates of attention opened up.

Ewers and his father suddenly found themselves sitting in Nick Saban’s office in Tuscaloosa, on a couch “like you saw in Napoleon Dynamite,” Ewers says, as the greatest coach in college football history tried to sell them on the virtues of playing at Alabama. Vince Young, the University of Texas legend, tried Ewers’s cell, but Ewers missed the call. He texted with Colt McCoy, another UT quarterback, who currently plays in the NFL. Ohio State, now coached by Ryan Day, stayed after him. In all, thirty-one schools made Ewers an offer.

Through it all, Ewers’s demeanor never seemed to change. “It was pretty crazy, but it was never overwhelming,” he says. He credits that, in part, to his faith. Like his parents, he is a devout Christian. He has “Luke 17:21” tattooed on his right (throwing) forearm, the Bible verse that includes the line “behold, the kingdom of God is within you.” On his chest is another tattoo, a cross with “Joshua 1:9” on it, a verse best known for the phrase “Be not afraid…for the Lord your God will be with you wherever you go.” Kristen got him that one when he was a young boy and had trouble sleeping.

Photo: Fredrik Broden

Curtis, Kristen, Quinn, and younger sister Teddy-Raye Ewers.

Ewers copes in other ways, too. He finds refuge with his friends. “You’d never know he’s in the spotlight,” Nate Gall says. “He never flaunts it and never talks about football unless you bring it up.” Ewers hunts and says he’s far more nervous over a shot at a deer than he is during a game. And he follows one steadfast rule: “When I need a break and don’t want to talk to recruiters, I just turn off my phone for the day.”

There was one time, though, when the veneer cracked, just a bit. In August 2020, Ewers verbally committed to play for Texas, the college team he’d loved all his life. (He says he’s watched the Longhorns’ 2005 national-title-winning game so many times he can narrate it from start to finish.) In late October, he told a journalist that he was “100 percent committed” to playing for Texas. Just two days later, though, he pulled the commitment. “It was a super-hard decision,” he says.

The backlash from Texas fans came swiftly, and they inundated Ewers’s Twitter and Instagram pages with nasty comments. It was the quarterback’s first scent of “the sad and silly wilderness of modern fame,” as the sportswriter Gary Smith once described it. Ewers has since reined in his social media diet. “I just don’t read the comments anymore,” he says.

What’s often overlooked in the college football recruiting world is that it is very much a two-way street. The Texas program, at the time of Ewers’s reconsidering, seemed to be in some disarray, and, indeed, at the end of the season the head coach was let go. “This isn’t just a four-year decision, it’s a forty-year one,” Ewers says, echoing one of Saban’s favorite sayings. A month later, Ewers committed to Ohio State, the program that first made him an offer in eighth grade and never gave up. “Coach Day and his assistants are really good guys, and my family and I have a great relationship with them,” he says. “And I like that they are in the mix for a top-four spot every year.” Still, nothing is official until Ewers signs a letter of intent later this year.

Ewers’s parents have had to figure out how to navigate all of this, as well. “There is no script,” Curtis says. At first, Kristen says, she felt protective of her son, because everyone seemed to want a piece of him. “But then I just took a back seat and was just a mom,” she says. “I cheer him on and make sure he has clean clothes.” Curtis, though he sometimes seems on the verge of bursting with pride, has chosen the same path, wary of the cautionary tales of fathers, in particular, going over the top with athletically gifted sons—fathers like Marv Marinovich, who famously wanted to turn his son, Todd, into the “perfect quarterback,” stretching out his hamstrings at one month old and banning him from eating fast food. (Todd Marinovich ended up in drug rehab after flaming out of the NFL.) “We decided years ago that we wanted Quinn to do this on his own and that we would support him by just being around if he needed us,” Curtis says. “We do normal parenting things. We have tough conversations when he messes up. But this is his journey.”

Though Curtis certainly played a role in his son’s football life—like installing a spread offense in peewee—he says he’s never pushed him, never scolded him for throwing an interception. He says he usually only finds out his son has spoken to a recruiter when and if Quinn brings it up. “We’re just trying to be sensible,” Curtis says. “We don’t worry too much about the fame. We just tell him to be himself. We could be naive. The risk is that you don’t know what the reward will be if you lay off. But we’ve decided to lay off.”

It helps that the Ewerses have surrounded themselves with a tight-knit group of adults who have their son’s best interests in mind, people like Dodge and the trainer Bobby Stroupe who have experience with all of this. It also helps that Quinn, though an introvert, actually loves the lights and the crowd, and feels “totally locked in” when he steps onto the field for a game. “His mentality is ‘I’m here to put on a show,’” Dodge says.

Everyone you ask has a favorite Ewers play. During his freshman season, he was called on to punt during a playoff game against DeSoto, and calamity struck: The snap flew high over his head. “Quinn was so casual,” Dodge says. “He just kind of jogged back, picked up the ball with one palm, then boomed a kick nearly sixty yards down the field that pinned DeSoto on their five-yard line. The crowd went wild, but Quinn just shrugged like whatever.”

In a game against Guyer his sophomore year, Ewers, now the starter, was flushed from the pocket on one play. “He’s running, and he’s almost to the sideline when he flicks this pass off his back foot, just sends the sucker, and it lands in the receiver’s hands, in stride, for a touchdown right at the back pylon,” says Luke Anderson, the family friend. “I saw Curtis after the game and said, ‘Dude, your kid’s a freak.’”

Last season, during a playoff matchup against Trinity, Ewers was flushed to his left. Just before getting hit by an oncoming defender, he transferred the ball to his left (nonthrowing) hand and completed a seven-yard pass to his wide receiver, Landon Samson. “That was pretty crazy,” Samson says. And in last year’s playoff semifinals, against nemesis Duncanville, one of his linemen’s helmets popped off and flew back at him as he dropped back to pass. “Quinn just batted away the helmet, rolled to his left, and threw the ball fifty yards for a touchdown,” Samson says. “I stood there and said, ‘I can’t believe he just did that.’”

Photo: Fredrik Broden

The Southlake Carroll trophy case.

When I ask Ewers for his favorite play, he smiles as if he wants to pass on the question. I press him. “I guess the one that clicks in my head was a seventy-three-yard touchdown run I had my sophomore year against Guyer,” he says. “It’s fun to make plays.”

Last season—Ewers’s junior year—started off with a bang. He threw for 388 yards and five touchdowns in his first game. But in the middle of the season, he suffered a core muscle injury that required surgery. He returned for the playoffs, and in the quarterfinals, he completed thirty-seven of forty-one passes for 450 yards and six touchdowns. Southlake advanced to the state championship game. There, the Dragons faced off against Westlake, the team coached by Dodge’s father, Todd. (Riley’s five-year-old son told his grandfather, “We’re coming after you, Pa-pa.”)

The game featured a top-notch quarterback duel, with Ewers going up against another touted Texas recruit, Cade Klubnik, a Clemson commit. Ewers threw three touchdowns to Klubnik’s one, but also uncharacteristically threw two interceptions as Southlake lost, 52–34. After the game, as Ewers stayed on the field to watch Westlake celebrate, Klubnik and the defender who had twice intercepted Ewers approached him. The defender happened to be carrying his plaque for being named the defensive player of the game. When asked about the encounter, Ewers smiles and shakes his head, comfortable keeping his thoughts to himself.

Photo: Fredrik Broden

Quinn with fellow Dragons Josh Spaeth, Nate Gall, and Landon Samson.

Now fully recovered from his injury, Ewers will lead the Dragons this fall in his last season at Southlake. Then he plans to graduate early, in January, so he can enroll at Ohio State in the spring to get in some early practice.

Meanwhile, the hype train continues to pick up steam. On a spring-break trip this year to Universal Studios with teammates Spaeth and Gall, a few people recognized Ewers, and one fan even asked for a photo.

Next year at this time, Ewers will face a raft of challenges: He will be away from home for the first extended period, at a big new school, competing against players—on his team and on others—with résumés nearly as shiny as his. There are no givens in life. But for Ewers, for now, anyway, it’s all still just a game and, like that three-year-old slinging spirals on that high school field, he still can’t get enough of it. “It’s 100 percent fun, all of it,” he says. “That’s a perfect day. When you’re having fun.”