Food & Drink

The Quest for Sack Sausage

A trio of devotees hit the road in search of a legendary taste of the past that’s hanging by a thread

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

LeeAnn and Bill Cherry’s sack sausage, ready for the fry pan.

“They used to call it carny,” Troy Smiley says, standing at the door of his smokehouse. “That whang you get after a sack of sausage hangs.” He wears jeans and a flannel jacket. His eyes glint with mischief. “We used to try to get rid of that whang,” Troy tells us, looking up from the dirt floor. “Now they want it.”

We are they: pilgrims who have traveled here in search of something we fear might go lost. March Egerton, a son of the late Southern thinker and writer John Egerton, stands tall and angular. Tyler Brown, the Franklin, Tennessee, chef, wears a newsboy cap over a mane of graying hair. As they ask Troy questions, I eavesdrop.

Troy’s family has made sack sausage since the early 1800s. That’s when Temperance and David Smiley settled on a ridgetop here in Robertson County, Tennessee, north of Nashville. They raised pigs and ground down the shoulder meat, spicing it and stuffing it in muslin sacks to dry and to smoke. The Smileys did this work for the same reason they made corn whiskey: to get more out of what they grew, so they could keep farming these sylvan hills that roll toward the Kentucky border.

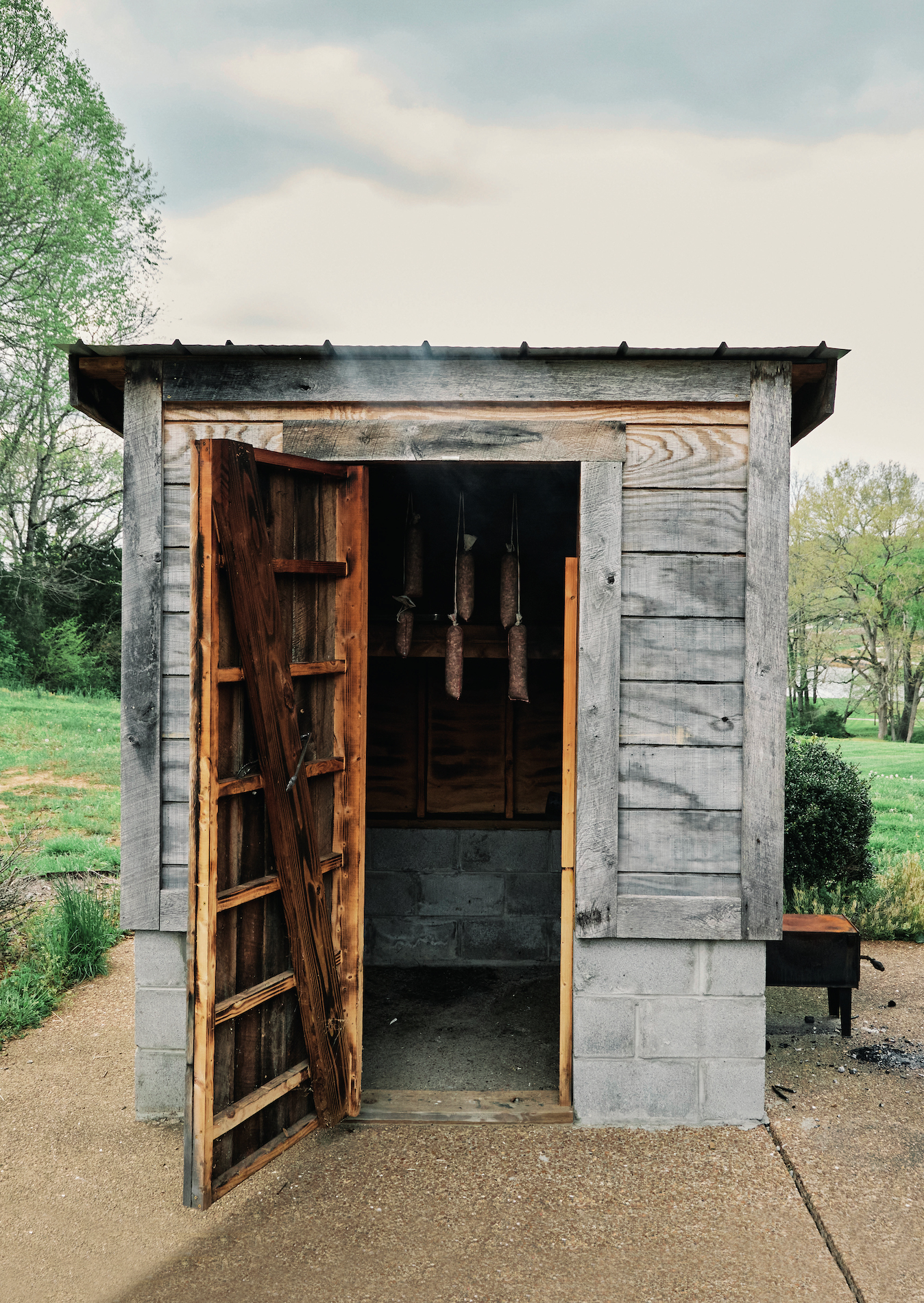

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Brown’s smokehouse at Southall.

Each winter, Troy still hangs a few sacks from the smokehouse rafters at Smiley Farms, scatters clumps of hickory and sassafras, and sets the wood smoking. The sacks, which some call socks, hang for a week or more, taking on that whang, that smoke, to render pork that tastes round and leathery, the way a Cohiba cigar smells or a Rioja Gran Reserva drinks.

Troy was slow to appreciate this craft. His son, Jacob, taught him who foodies are and why they obsess over the work of farmers. Troy also learned what it took for a brilliant young man like his son to live as a gay person in Tennessee. “We were food snobs together,” he says as his face softens and his eyes shine bright. Until Jacob passed at age twenty. Loss can magnify beauty, Troy suggests. And taste can carry forward memories.

Today, government regulations prevent Troy from selling those sausages. So he gives them away, sometimes to lucky pilgrims like us. An act of grace from a graceful man.

To tell the story of that sausage, Troy moves back in time to when he was a boy, listening in on relatives and neighbors. He’s ten or twelve. He’s cold. It’s winter. Troy squats in the lean-to by the side of the barn. He looks up into the faces of the old men.

Hunkered in the morning air, they argue over how long to hang those sacks of ground pork, mixed with sage and salt and red and black pepper. They talk about how long it takes for the moisture to be wicked away and the smoke to take. About how sweet sassafras complements hickory. They speak of “doady” wood, soft, crumbly hickory that will smolder all day. And they talk about that whang, what the old men called carny. Today, as Troy puzzles over what that word must have meant to them, he figures it could have been a riff on the word carrion, a reference to the bridge that spans life and death and decay.

Tyler and March also know that whang. March’s father introduced them to it. Same as he introduced me. Each December, John Egerton, who thought of traditional foods as connectors across cultural and generational divides, would ship out gifts of Trigg County sack sausage, smoked by Doug and Euneda Freeman on their farm near the county seat of Cadiz, Kentucky. All on that list remember that sausage as the best they’ve ever had.

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

From left: The author on the road; chef Tyler Brown with a few sacks at Smiley Farms; March Egerton.

Since John died unexpectedly in 2013, March has deflected efforts to deify his beloved father. He wrote insightfully and meaningfully about the South, March says. He gave much to many, most of all to his family. And he knew great sausage when he tasted it.

Like John, the Freemans have now passed. In their wake, that sausage has become scarce. Along with government regulations, changing diets and rural-to-urban migrations are the likeliest culprits. As we drive a triangle-shaped region, defined at the bottom by Nashville, in the west by Paducah, Kentucky, and in the north by Owensboro, we talk about how this area was also historically home to some of the South’s best ham curers. And we wonder if sack sausage will gain new value as a new generation discovers this country cousin of country ham.

Late this spring, Tyler and his colleagues plan to open Southall, a luxe farm resort south of Nashville just outside Franklin. To showcase old knowledge in new ways, they have built hydroponic greenhouses and grafted forty varieties of apple trees. When Southall opens, Tyler will grind corn on a century-old millstone. And he will stuff and smoke sack sausage, inspired by his long friendship with John Egerton.

Tyler talks about sausage with precision, born of two decades in restaurant kitchens. He measures spices in grams. And he charts the chemical reactions that previous generations suspected. That whang, he says, comes from fermentation, from bacterial conversion of sugars in the ground pork into flavors. Along with smoke, that’s what makes great sack sausage great.

After Euneda Freeman passed in 2010, when Doug was too sick to make sausage but not too ill to advise them, John and Tyler would meet at the Hermitage Hotel in Nashville, where Tyler then led the kitchen. They puzzled through how fine to grind the shoulder meat and how much sage to put in the mix. To get close to the sausage that Doug made and John gave away, they worked up batch after batch. No matter what John brought Doug to taste, he told them to try again.

Today is Thursday. Before this three-day road trip is over, we will land in Trigg County, where John Egerton and March’s mother, Ann Bleidt Egerton, grew up, and where March often visited his grandparents. On the outskirts of Cadiz, we will gather beneath a spreading oak with the descendants of Doug and Euneda Freeman, who will fry sausage in cast-iron skillets and talk about what both families lost when their elders died, and what they left behind to inspire us.

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

LeeAnn and Bill Cherry in their kitchen near Franklin, Tennessee; visiting with Broadbent Country Ham owner Ronny Drennan.

Country ham makers like Nancy Newsom Mahaffey in Princeton, Kentucky, whom we detoured to see, have developed new markets for their old products. Their best hams fetch more than thirty dollars per pound. But sausage, even really good sausage like the stuff Tyler and March covet, goes for around eight dollars per pound. Foodies, like the ones Troy Smiley came to know through Jacob, have not yet claimed sack sausage. But new energy now mounts in and around Nashville.

Before meeting with Troy, we visited Nathan Gifford, who works out of a former transmission repair shop on an industrial stretch in East Nashville.

He cures bacon and ham, smokes sticks of bologna, and stuffs sausage sacks with a mix of pork butts and bacon ends. The old ways inspire him, Nathan told us, standing in a gravel lot littered with smokers and burn boxes. But he plays a different game in his sausage room, maintaining a steady thirty-eight-degree temperature and an air speed of five miles per hour.

Nathan makes good sack sausage. His smoked bologna is even better. Now that he has earned his USDA stamp, he can do something Troy Smiley can’t. He can sell his sausage and other Gifford’s products to retailers. And ship to people like you and me.

LeeAnn Cherry farms down near Franklin. She and her husband, Bill, made their name raising beef cattle and selling beautifully marbled prime steaks. When they bought another farm near Centerville, it came with a smokehouse, she told us later that afternoon as we stood at their kitchen island and Bill fried sausage patties. That piece of land was pretty, she said, but the real reason they put down money was the smokehouse. She and Bill started making sausage last year, using a recipe developed by the Nashville chef Sean Brock, who was inspired by the recipe Tyler developed with John.

She, too, hopes to win USDA approval, and Sean wants to use her sausage at Joyland, his biscuit and chicken spot down the street from Gifford’s. Before we leave, she loads us up with test batches, stuffed in white muslin sacks, tobaccoed brown with smoke. We wedge them next to a cooler stacked with Gifford’s smoked bologna. And we drive on.

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Richard Tinsley, a regular at Newsom’s Old Mill Store in Princeton, Kentucky; Troy Smiley at Smiley Farms; country ham maker Nancy Newsom Mahaffey.

Friday shines bright and clear. As we head north on I-24, the towers of Nashville recede. An hour and a half later, we pull into Broadbent Country Ham. Set alongside a truck stop near Kuttawa, Kentucky, with a gift shop up front that displays county fair ribbons and sells “Bless This Kitchen” hand towels, the prefab metal building looks like a small-town roller rink. After a tour of the aging rooms, where owner Ronny Drennan and his crew reproduce the effects of four seasons of weather changes on salted country hams, and a detour to a room where sacks of ham bones hang in smoke to become dog bones, we take seats in Ronny’s office to talk sausage.

Ronny ships his products nationwide. To do that, he has adapted old ways to new technologies. He now uses a machine called a smoke generator, a bulky, noisy thing, connected to a tangle of hoses. “There’s no live fire to make my insurance agent nervous,” he tells us. The sacks he sells, blazoned with Grandma Broadbent’s name, are flat-out delicious. They bloom with fragrant hickory. But like most we have tried so far, they lack that whang. Walking out, we pass a fellow in overalls walking in. He tilts his head back, takes a deep breath, and shouts, “I just came to smell!”

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Nathan Gifford in East Nashville; the Freeman family at their Trigg County farm; grinding sausage meat at Southall.

When we call to confirm our visit with Charlie Gatton, the owner of Father’s Country Hams over in Bremen, Kentucky, he’s still planting corn with his son. He had planned to finish by dinner, which up here still means lunch, but when you farm two thousand acres, time is relative. It’s past four when we reach his brick rectangle of an office, flanked by two big concrete hogs.

Charlie was born to this work. When his father died, in 2000, he took over a business that was already fifty years old. To make sausage, he smokes hickory clumps and sawdust. Sometimes he adds a hickory slab or two. The smoke gets so dense, Charlie tells us, standing at the threshold of the smokehouse, that last year he got turned around inside. Even with a flashlight, he struggled to find his way out.

We snag a sock apiece and a bag of country ham jerky bits that Charlie markets as Squealers. As Tyler sets the GPS, I call my wife to tell her the story about Charlie getting lost in the smoke. Blair texts ten minutes later, “There’s a metaphor in that, isn’t there?” Her point, I think, is that all of us who search do much of that work in the dark.

Closing in on Trigg County, March works his phone, pinching and scrolling a map, narrating the contours of his childhood. A creek ran by here, where, as a boy, he nearly drowned. Ahead is the tree where he carved his initials next to those of his mother’s father. That road up there leads to the dairy bar that only opens in summer and puts that weird pineapple goo on soft-serve cones.

Twenty years ago, when this crew was in our twenties and thirties, our car would have stunk of spilled beer by this point in a road trip. This morning, Tyler’s SUV smells instead of pork and smoke and time. Our payload shifts. A sack from Troy, dimpled by aging, rolls around in the back hatch. Tucked above the wheel well is Tyler’s own version, speckled brown by smoke and trimmed in red twine.

The Freemans have gathered in metal folding chairs around a couple of fryers, set with cast-iron skillets, popping with slices of sack sausage. Down the hill, behind the old homestead, loom two gray-board smokehouses. The smells of smoke and pork ride the early evening breeze.

“My father thought a lot of your father,” Randy Freeman, the oldest child of Doug and Euneda, says, tossing away a cigarette, gripping March’s hand. The feeling was mutual. John Egerton revered Randy’s father. For the work he did, and for the man he was. As I listen, I wonder if that respect also arose from Doug’s decision to stay here, where he grew up. To make a life as a writer, John left the rural South, as many of his generation did. But men like Doug Freeman and Troy Smiley stayed.

In his prime in the 1980s, Doug cured six hundred hams a year. For that work, he won grand champion at the Trigg County fair three times. The last eighteen hams he cured still dangle from the smokehouse rafters here. Shrunken by time, they glow amber in the slanting sun, tombstones to a craft now on the wane.

“It looks like a hotbox out of Cool Hand Luke,” March says to Randy as they step inside to inspect the tight confines and the smoke-stained walls. If my read of Euneda’s scratch on a price list tacked to the wall is right, the best sack sausage in the world once sold for around three dollars a pound.

After Euneda died, the family recipe went missing for a while. Shirley, Randy’s little sister, found the scrap of paper tucked in a cookie tin. The Freeman children still make sausage in much the same way their parents did. In a repurposed cattle trough, they burn down hickory and sassafras sawdust from a local mill. Stuffed in sacks, that sausage spends ten days in cool smoke. Recently, a new generation joined the effort when the Freeman grandsons began making sausage and sharing it with family and friends.

As we talk, a skittish cat weaves between legs and darts into shadows. That was Euneda’s cat, the middle brother, Donnie, says. “No one can remember his name.” Randy can’t remember either. “Was it Biscuit or Cornbread?” What Randy does remember is to feed his mama’s cat. Each day he drives out here to replenish the silage for the cattle he raises on the land his father worked. And each day he pours cat food from the co-op into a stainless-steel pan from his mother’s kitchen, placing it in the old doghouse the cat now claims as home.

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Cooking sack sausage with the Freeman family; ribbons on the wall at Father’s Country Hams; on the hunt.

On the drive back into Nashville the next morning, we stop beneath cloudy skies in the parking lot at Joyland, where March parked his car. Eager to taste and compare what we gathered, Tyler has set up a camp stove and a skillet on his tailgate. He cooks samples from the stuff that we collected over the weekend. And after we try them all, he pulls out his own version, a fifty-fifty mix of lean and fat that hung for seven days.

Before March peels off to go watch his son play in a basketball scrimmage, he makes the call. They all show good smoke, he says, but Tyler’s has that whang, the taste we all remember from the sausage Doug and Euneda used to make, the sausage we all fear might disappear. Tyler smiles proudly, but in his head he can still hear Doug saying, Try it again.

At Southall, we unload our provisions onto a stainless-steel table in Tyler’s development kitchen. Like grade-school kids jacked up on candy at a birthday party, we inspect what we have hauled home. We trade sacks. We sniff sacks. Tyler figures a little more sage might take him another step down the road. So he gets to work.

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Unloading the spoils; frying up a taste; Smiley takes in a smoky whiff.

Tyler crushes spices. He feeds chunks of pork shoulder and fatback into the grinder. He stuffs the sausage into muslin bags and moves toward a recently installed smokehouse fired by a squat cast-iron stove. He hangs five sacks from the rafters, lights hickory and sassafras, and seals off a duct leak with a piece of cardboard.

After the bacteria do their work and these sacks emerge, Tyler will know whether he got this batch right. For now, we stand back to watch and hope. Woodsmoke curls from beneath the eaves. As the sun breaks through the clouds, March walks up from his son’s basketball game, an expectant smile on his face. He sniffs the air, ducks a wasp that has fled the smokehouse, and moves toward that smoke, stepping forward into the past.