To everyone else on Sullivan’s Island that Saturday morning, the day must have looked like any other. My friend Bobby and I stood in his backyard, the Intracoastal Waterway winding just beyond. In a yard to our left, an old man napped neatly folded into his hammock, rocking gently in time to the beat of Bobby’s boat on the dock. Farther on, two Labs danced and paced as their masters loaded their own vessel with tackle and coolers. Another neighbor slowly slopped a fence with a fresh coat of Charleston green. But Bobby and I were not there to while away the weekend like the others. We were there to say goodbye.

Bobby’s tears still ran fresh on his cheeks from a cry he had had moments earlier. He had chosen this setting, and this day, for his dog’s last breath. The home where he lived with his wife, Kristin, and their three children, the one bordered with a low chain-link fence, erected not so much to keep the world out, but to keep Abby in.

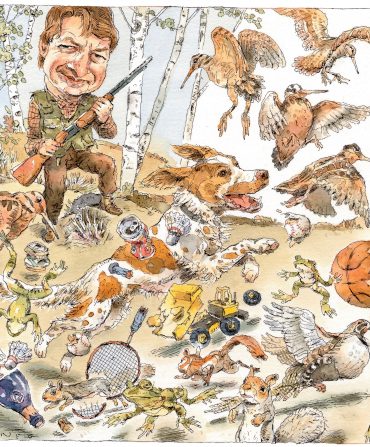

Boykins are a notoriously busy breed—they need a job to serve as a pressure release for the energy that winds through their coils. Abby’s task was to hunt and retrieve. And for ten years, she had performed the commands Bobby had taught her when she was a pup with puritanical zeal. After time with Bobby in the field, Abby would return to Kristin and the kids gentle and loving. She welcomed either role—retrieving downed fowl from the waters of the ACE Basin, or fetching a toddler-tossed tennis ball from the creek. She was the perfect family dog.

Until she began to skip meals. Then Bobby and Kristin brought her to me.

Sixteen years earlier, I had walked away from hosting a radio show here in Charleston, South Carolina, to pursue a dream of working in animal medicine. One of the unfortunate functions, though, of being a veterinarian was this—bringing about the end of a life. As I examined Abby, I couldn’t help but think of my own dog back home, ravaged by bone cancer. Soon I might be in Bobby’s place.

Abby’s decline had happened more gradually. Even when her vision dimmed due to anisocoria—pupils of unequal size—the family took it in stride. But two years later, not eating raised a red flag. This dog lived to hunt, lusted for a chase, longed to play, and loved to eat. I discovered a mass in her mouth, along the midline of her hard palate—an area the size of a plum had softened under the appetite of the tumor. A laser procedure and a biopsy were all the pathologist needed to deliver a diagnosis of oral melanoma: a locally aggressive and ruthless bitch of a cancer.

The tumor was inoperable and chemo impractical given the location. This is always the worst moment: when you look into the eyes of an owner and explain not if their dog is dying but when. At least Bobby and Kristin were hearing it from a friend. We agreed Abby would not linger too long—they would choose when to say goodbye.

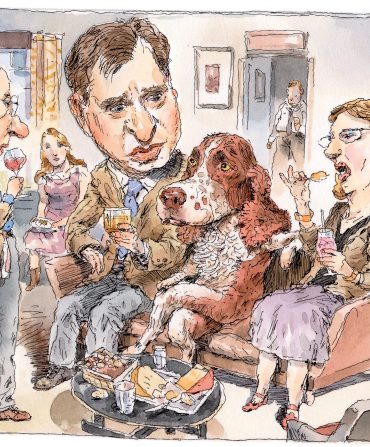

So Abby retired to her home on the water to be lavished with affection and the finer delicacies, when she would eat: steak, seafood, pastas—life was good. As good as a welcome mat on death’s doorstep can be.

Then, just a week after the diagnosis, on a Wednesday, Abby’s appetite vanished completely. Bobby decided the sooner the better to put her down, and we settled on that Saturday. “She’s miserable,” he told me. I wrote a prescription for buprenorphine, a potent analgesic for Abby that also gave the family exactly what it needed: time to make a lasting memory.

On that Friday, Abby, now comfortable, spent the day chasing a tennis ball and riding through the Lowcountry in Bobby’s boat, and that night five humans wrapped her in their arms, cried into her fur, and embraced her like there was no tomorrow. There would be another tomorrow, but only one.

When I arrived with Dawn, a technician from the clinic, the sun was directly overhead. Bobby and I strolled into the backyard, where he told me that Kristin and the kids were off “doing some errands.” The young ones would be spared.

The night before, Bobby’s seventy-five-year-old neighbor, Waring, had helped dig the grave after the kids had gone to sleep. Together, the two of them hollowed a patch of earth near the rosebush Bobby had replanted from his mother’s garden after her death. As he and I stared into the grave, Bobby lost what little composure he had held onto. I put my arm around him and reminded him he was doing the right thing. He put his arm around me, and shared the details of the previous day. Abby’s last glorious run.

Or rather, next to last. At that moment, Nurse Dawn and Bobby’s father-in-law threw open the back door to join us, and Abby lit out through the exit between them, on a mission. A joyous smile returned to Bobby’s face. “Get dem birds. Get dem birds, Ab!” he bellowed. Abby sprinted across the property toward us, contorting and twisting her thin body on arrival as her head frantically swept the yard for nonexistent quail. Two steps toward the fence, a quick couple of hops back, a cursory glance aft, and then finally she cast her attention toward her master. Once she was locked on Bobby, he tossed the tennis ball. Abby had it in her mouth before it had quit bouncing. Three quick blasts from the whistle around his neck, and she set the ball deftly at Bobby’s feet.

Toss, whistle, and repeat.

Between the tosses, there was an anecdote and a tear. We listened to hunting stories, recollections of Abby with the kids, and the simpler visions that the dog had burned into Bobby’s memory. Abby, perched on the bow of the boat. Abby, lying at the feet of his children as they slept. Abby, patrolling the kitchen floor for stray scraps of food.

Any neighbors looking over the fence line that day might have thought they were witnessing a normal, healthy dog. They could not see the cancer dissolving the bone in her mouth, and they could not know she had avoided food for the better part of seven days. They could not feel the despair of the family as they had watched their dog surrender in a heap of lethargy each night. And so Bobby would sacrifice more time with his dog for the sake of her comfort, and her dignity—in his family’s memory, she would never be less than the Abby they knew.

We all settled on the blanket, with Abby on Bobby’s lap. With my hands making a tourniquet, Dawn found the vein. Abby slept quickly. I placed the bell of my stethoscope over her chest—not only to hear her heart as it slowed and then stopped, but to block out the rawness of Bobby’s anguish. And then she left us peacefully.

Bobby covered her body with one of her favorite blankets. Slowly, he lifted the training whistle from his neck, and paused before gently laying it upon her. He then quietly spoke to Abby, private words I could not hear.

As Bobby raised himself from the hole, he looked at me. “A last toss?”

I nodded.

He flipped the ball into the grave. “Get dem birds, Abby,” he whispered.

I grabbed the spade, but before I could deliver the first shovel of dirt, Bobby snatched it from my hands. “I got this,” he said. “I need to do this.”

When the hole was filled, Bobby carefully set Abby’s collar on the fresh dirt, adjusting it two or three times until he deemed it perfect. He turned to the cooler near the kids’ swing set and asked, “Now, who would like a beer?”

The four of us sat on the swings or leaned on the crossbars and swapped tales about the lives and deaths of animals we had owned and loved. We sipped and talked and teared up and laughed for half an hour. In that time there were moments of silence, where each of us held a private audience with some special animal as the tidal marsh patiently listened. My dog Nokomis was waiting at home. She, too, would have a last toss all too soon.

Bobby stared at the grave of the best dog he ever had, and the sound of the backwater seemed to speak to us. Close your eyes, my friend, throw it far, and toss it deep—Abby will forever carry it home.