That dogs are emotional creatures—that they keen with sadness, leap with joy, wiggle in friendship and waggle in play, that they endure heartbreak and separation—is a thing well known to all who count these fascinating creatures among their best friends. But that dogs suffer neuroses? That they can be crippled by anxieties buried in their tribal past? That fears as deeply buried as last year’s bones can ooze up out of the primordial pink of their brains, and keep a dog from being all the dog that she can be? Or that their genetic pools might get as twisted and polluted as ours do? I had no idea, until I met Ozzie.

There was something off about Ozzie from the moment she entered the lives of her owners—dear friends of mine, so I was able to observe her case at a close distance over many years. She was adorable; what puppy is not? A chocolate Lab, full of bounce and energy, Ozzie never met a shoe she did not chew. But what was cute in a baby was less so in an adolescent, and intolerable in a young adult. Dogs, as you know, have a way of bounding through these stages at warp speed.

Ozzie seemed untrainable. It wasn’t because of poor parental skills, lack of discipline, hazy directives, or old-fashioned spoiling, all of which were, to my critical eye, on full display. Those sweet, indulgent friends of mine did finally send her off to boot camp so that she might have a chance to pull herself together. And it worked, sort of. Still, Ozzie could not stop chewing. Chewing herself, that is.

And she was chronically depressed, putting on weight, listless, turning her back on all the doggyness the world had to offer. Finally, she was diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Before too long Ozzie was chowing down Prozac, or Wellbutrin, or some such chemical cocktail, so that she might have a chance at a full and happy life.

As I mentioned, Ozzie was a Labrador retriever. We were living on the coast of Rhode Island, and we went to the beach every day to walk and play. When Ozzie was a puppy, I looked forward to doing that thing everyone does with Labs—throwing balls and hunks of driftwood into the ocean, watching as their Labs hurtle across the sand, dash out into the foaming surf, and retrieve the things, jaws clamped down purposefully, commandingly, and, then, battling the break of waves, riding the swells, return joyfully triumphant to drop the thing at their owners’ feet, gaze soulfully up, brimming with quiet dignity, tail wagging proudly to do it, please, just one more time.

But Ozzie was afraid of the water. Very, very afraid of the water. She wouldn’t go near it. She would bark at it, from a safe distance. She would paste herself to our legs when we walked the shoreline, making sure she stayed on the far side of the surf. She made a halfhearted attempt to chase a gull or two, but they seemed to know instinctively (as if you couldn’t tell by looking) that Ozzie was no threat. It was pathetic.

This was when I began to suspect that something was really wrong. But as I said, she wasn’t mine; and as anyone knows who has reared her young, you don’t get a lot of points for being a backseat parent. Besides, she was already on drugs to control the OCD thing. We weren’t expecting to take her, or ourselves, for that matter, hunting for ducks, so what did it matter if she wouldn’t and couldn’t swim?

It mattered to me. There is almost nothing I like more than the heavy, satin feel of cool ocean water against my bare skin. All winter, I remember the way that water caresses me, and holds me and lifts me in its swells and then parts for me as I glide through it. I pine for the ocean. I long for spring, when I can go in up to my knees. I swim every day as late as I can into autumn.

I envied Ozzie’s thick, oily coat, which seemed impervious to frigid temperatures; I wanted those large, powerful neck and shoulder muscles. Ozzie had all the right equipment. But she was wasting it. And besides, I don’t believe that drugs are the answer to everything. I believe in talk therapy.

I knew that quite often, depression is born of powerful inner conflicts that cannot be expressed, much less resolved. Ozzie seemed to like talking, though it didn’t help her swimming problem.

It was vexing, to see Ozzie suffer as she hit middle age; vexing to watch her backslide and attack her paws, vexing to trip over her at the beach whenever the water dribbled too close. I am not the sort of person who can turn her back on other people’s problems. In fact, I like nothing better than a mess to clean up.

One day, I had an idea. I decided that somewhere deep down inside, Ozzie knew that she was a swimmer. She knew she was supposed to frolic in the surf; she knew she was meant to pull through cold water. Ozzie knew all this, in her doggy, Labby soul. She was stuck, and becoming ever more entrenched in denying her true, retrieving, water-loving self. And what is neurosis if not the unhealthy repetition of actions that make one unable to be one’s true self? Fear had won the day—and this had embarrassed and humiliated and shamed Ozzie. She could not see a way out.

But I could. I would teach Ozzie to swim.

We went to the beach. It was a still, cool day. The ocean was calm and the light on the water dazzling. There was only a gentle breeze, and the surf came in with hardly a ruffle. Ozzie and I wandered away from her family so that we could be alone. She trusted me; after all, she had watched, fearfully barking and whining, for years, as I had gone into the water, paddled around—and returned safely!

When our privacy was ensured, I sat down next to Ozzie in the warm sand. I began to talk quietly to her about the water, which cloaked our conversation in the classic white noise of the psychiatrist’s office. I told her how much I loved the water, and how good it felt. As I talked, I moved slowly, gently, closer to the tide line. Ozzie huddled next to me. A bit closer, and the water was lapping at my haunches. Ozzie’s attention seemed riveted on my face, as if she knew that something important was about to happen.

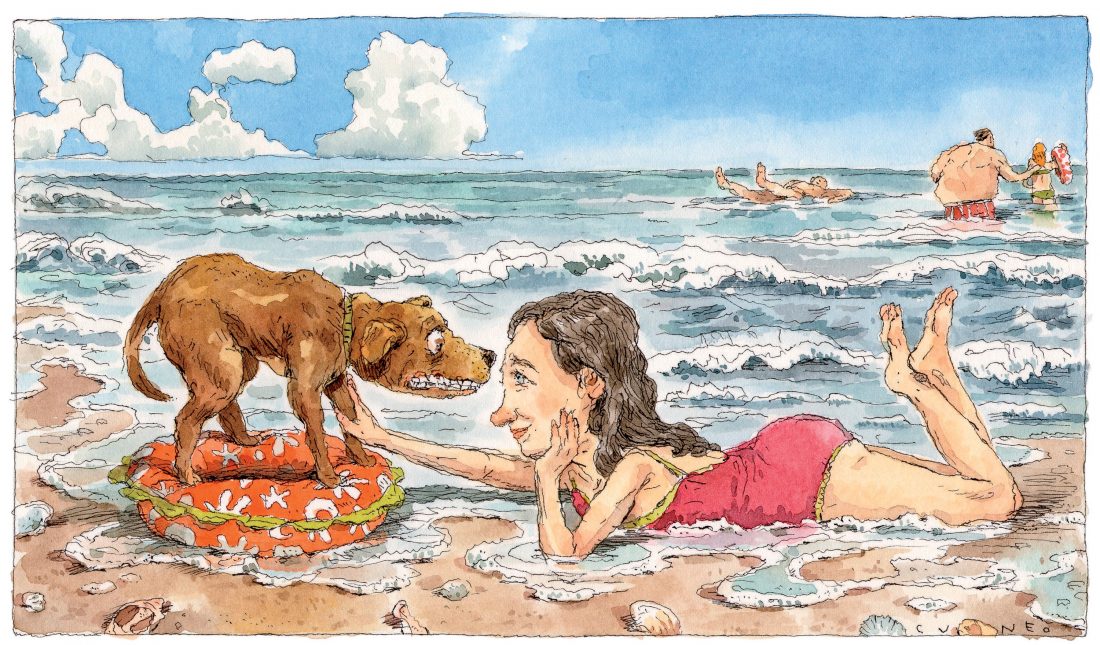

I held her paw in my hand, as we sat, and as the waves came up, she flinched a bit—I could feel a shudder pass through her—but then she settled down. The waves kept coming back, as is the way of waves, and the tide began to rise, as is the way of tides. But still we sat. Before too long, we were sitting in a few inches of water, just holding paws. I coaxed Ozzie into a lying-down position, and I got onto my own tummy. I had actually never simply lay still and let the water ripple around me, and it felt surprisingly lovely; I was clearly having personal breakthroughs of my own.

Soon the water was high enough to give me some buoyancy. I pinned my elbows into the sand and faced the waves, tadpole style. Ozzie scrambled to her feet, but she stayed next to me. I moved a bit deeper into the water, and Ozzie began wading. I laced my arm around her leg and up under her neck. She knew I was right there with her. She was knee deep, then gut deep, determined to stay on her feet. I let a wave push me up against her, and gave her a little bump, just the tiniest shove, and Ozzie was off her feet—just for a few seconds, until the wave retreated. This happened eight or nine or ten times. Ozzie let herself become buoyant, and then she settled her paws back into the sand.

And still we talked. About the nature of life. About how waves came in, and went out, because that was what waves had to do, and about how people, and dogs, and ducks went into the water, and came out again, because that was what dogs and people and ducks do. (I don’t know why I brought the ducks into the picture; perhaps it would trigger some atavistic response.)

By then we were in pretty deep, as far as Ozzie was concerned. I took her paw again, and on the next wave, the next moment of buoyancy, I crooked her leg, and showed her how to paddle. She backed off, so I told her I would do it, a little dog paddle just the way people learned to swim, and just the way other dogs did it. Then I hunched down next to her, and took both her front paws, and paddled them through the water, to give her the hang of it. I could feel her heart pounding against mine.

Ozzie was getting excited, I could tell. A spark lit in her eyes. She looked at me, and I smiled. She smiled back. We started moving along, keeping shallow, in a combination of crawling, walking, and paddling. Before too long, we were in far enough that neither of us could crawl or walk. Before too long, we were swimming. And I was cheering. “Wonderful, Ozzie. Good dog, Ozzie. You are doing it, Ozzie. That’s fantastic. Beautiful, good girl, Ozzie. What a great dog you are” and all the other things, exaggerated with love and pride, grown-ups say to small ones who are conquering new frontiers. I stopped holding her paws to help her; she moved rapidly out of my training arms.

Ozzie was swimming.

On the shore, her family had gathered, and they too were cheering excitedly. Ozzie glanced around, a new fortitude in her shoulders, but she was concentrating too hard on her new skills to pay much attention to their shenanigans. I stayed right next to her, dog-paddling too, bobbing against her side, talking, cheering, being present. She yipped back from time to time. We talked about what it meant to give in, to relax, not to fight. About what it meant to let go of fear.

That was how Ozzie learned to swim. And as far as I was concerned, that was how Ozzie finally became…more of the dog she was meant to be. She would never be a duck hunter’s trusty companion. But Ozzie had retrieved just a little bit more of her soul.