On a recent episode of The Slowdown poetry podcast, the host Ada Limón recalls encountering a cow standing in the middle of a country lane while out walking. After a few beats, the cow turned and ambled back into its pasture. “I had just moved to Kentucky, and I was full of doubts about how I felt about the place,” Limón says. “Seeing that beautiful white cow just standing there in the middle of the road made me wonder about what it means to choose freedom and to choose home.”

Born and raised in Sonoma, California, Limón had lived most of her life on the coasts. She majored in theater at the University of Washington and later moved to Manhattan, where she worked in magazines and earned an MFA from New York University. She relocated to Lexington, Kentucky, with her now husband in 2011 and has since grown to embrace her chosen home.

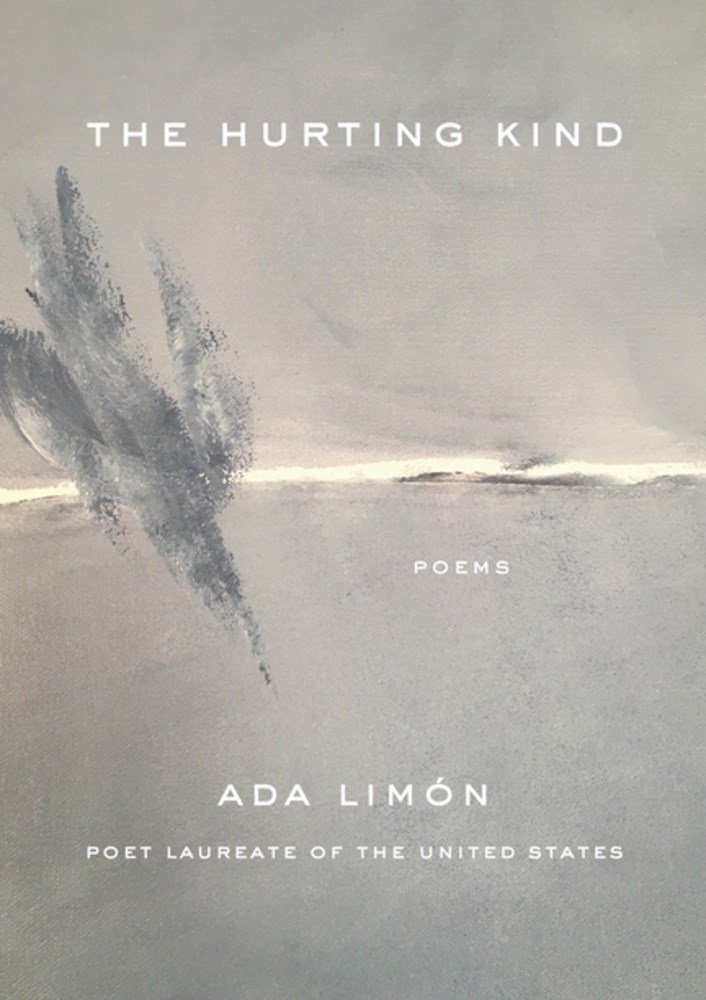

While allusions to nature are a hallmark of her poetry, Limón’s work in recent years reflects a growing Southern sensibility and sense of place. Milkweed published her sixth poetry collection, The Hurting Kind, earlier this year. Limón was recently appointed as the twenty-fourth Poet Laureate of the United States and will deliver her first reading at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., on September 29 to open its literary season. We chatted with the author about her new posting, Kentucky inspirations, and her constant writing companion: a pug named Lily Bean.

Congratulations on being named Poet Laureate. Did the invitation come as a surprise?

The invitation was absolutely a surprise—it’s not something you apply for. I’m such an organized person that, at first, I felt like I needed to know all the things right away. The orientation at the Library of Congress has been helpful and being in the library has really helped to ground me. I have a beautiful office there that looks out over the Capitol. It’s the largest library in the world and getting to know it would take a lifetime but, reading room by reading room, I’ve been able to experience some of its incredible collections.

How do you plan to approach the position?

The primary goal for me is to make sure that I’m a good spokesperson for poetry and that I speak not only to its existence, but also to its power and how it can transform our hearts and souls. How can we lift up poetry for everyone? How can we make it accessible? How can people experience poetry in new ways? Once I reframed that for myself, I felt more comfortable in the role. It’s service for the sake of the thing I believe in the most, which is poetry.

Poetry had a huge moment in recent years when Amanda Gorman delivered the inaugural poem.

I think there was something about hearing the particular music that she created—that idiosyncratic voice, especially at that moment—that felt like it was it was doing the work of healing. When those moments happen, what do we turn to? We turn to poems. When someone passes away, when someone gets married—the biggest moments in our lives long for poetry. So, why not also incorporate it into our daily lives?

It’s important to me that my poems are not only for other poets. I love other poets and I love my literary community, but I would also like for someone who has never read a poem to find something in my work, even if it’s maybe an entryway into reading more work by other people.

Is there a common theme that runs through your poetry?

What’s underneath a lot of my poems is the idea of our mortality—this one life. Some people may find that disheartening or overwhelming or just plain sad, but the idea of mortality allows me to recommit again and again to each day and each moment and to hold it with joy or tenderness.

The other part of it is, if we do have just this one life, what can I honor? What can I offer? This last book, in particular, feels like an offering. It’s offering poems to my father, to my grandfathers and to my grandmother, to my mother, my stepfather, and to my brothers. And then also to the trees and the plants. It’s a book that, when I finished, I thought, ‘If I get struck by lightning tomorrow—which would be a very dramatic way to go—I will have said thank you.’

You often write about plants and animals with the same affinity.

When I’m feeling down or harried or like my brain is rushing, I can stare at trees for hours. I’m looking right now at my silver maple shaking in the wind like it’s doing a sort of performance dance piece. Poetry has that same effect on me. Writing or reading about the natural world and looking deeply at nature reminds me that we’re part of something larger and that our relationship with the Earth is reciprocal.

What were your first impressions of Kentucky?

One of the things that surprised me was how stunningly beautiful the land is. My husband is in the horse racing industry, so we would drive from farm to farm and look at these incredible spaces and pastureland. Everything was blooming and it was gorgeous. The dampness, the allergies—but also the hundreds of different kinds of grasses and trees. I remember pointing out a tree that I’d never seen before, and someone said it was a sweet gum tree. I thought, ‘What a great name. Sweet gum tree.’ Connecting with the land was a big part of me connecting with Kentucky.

And then, slowly but surely, I started to find the writers. I met people like Crystal Wilkinson, Frank X Walker, Manuel Gonzales, and Silas House. There’s also the legacy of Wendell Berry and bell hooks. Maurice Manning really welcomed me, and Jeremy Paden… so many people. Finding the writers is like finding the heart of a place.

In a Good Dog column for Garden & Gun, you wrote about how adopting your pug, Lily Bean, helped with the transition of moving to a new state. How is she doing?

She’s eleven now and is doing great. She’s lying down next to me right now—the other day I was calling her the ‘Poet Snoreate,’ because she snores so much.

She’ll sometimes do this thing where if she’s inside she wants to go out or if she’s outside she’ll want to go in—she’s constantly making me move, which is good for me. When you’re always sort of introspective and in the mind, it helps to have this little soft being that needs your attention and love and always brings you back to reality and what’s important.