In the course of his five-decades-long career, James Brown (1933–2006) thrilled, shocked, inspired, disappointed, exasperated, comforted, roused, galvanized, polarized, and sometimes flat-out warped the minds of the American public. To say that the singer was a hive of contradictions is true—he cowrote the fiercest of civil rights anthems, “Say It Loud (I’m Black and I’m Proud),” yet held segregationist Strom Thurmond in affectionately high esteem—but eludes the concurrent fact that we too, his countrymen, are a hot mess of contradictions. The James Brown we saw tended to be the James Brown we chose to see: as the caped crusader of funk and soul, adored by millions; or as the face in a seemingly endless series of mug shots. The ways in which he appealed to and appalled different audiences made Brown a kind of national Rorschach test.

In Kill ‘Em and Leave: Searching for James Brown and the American Soul, the author James McBride puts it this way: “To the music world, he was an odd appendage…a large rock in the road that you couldn’t get around, a clown, a black category. He was a super talent. A great dancer. A real show. A laugher. A drug addict, a troublemaker, all hair and teeth. A guy who couldn’t stay out of trouble. The man simply defied description.

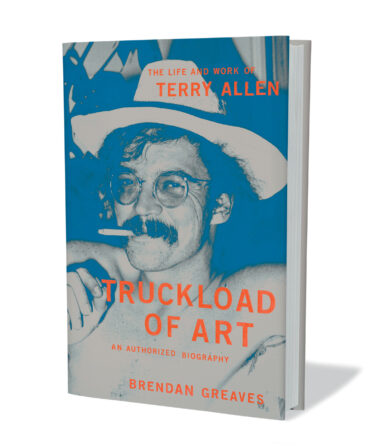

Photo: Margaret Houston; David Corio/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Kill 'Em and Leave: Searching for James Brown and the American Soul

Spiegel & Grau, $28

“The reason?” McBride continues. “Brown was a child of a country in hiding: America’s South.”

Though Brown has been the subject of more than a dozen books, including two that he himself had a hand in writing, he remains an enigma: “arguably the most misunderstood and misrepresented African American figure of the last three hundred years,” writes McBride, whose 2013 novel, The Good Lord Bird, won the National Book Award and whose 1995 memoir, The Color of Water, has sold more than 2.5 million copies. (McBride is also a working musician, having toured with jazz legend Little Jimmy Scott and written songs for Anita Baker and Grover Washington, which lends heft to his musical analysis.) Kill ’Em and Leave is a tight assemblage of reporting, biography, and cultural dissection, held together by McBride’s gutty, jangling, and sometimes smoldering voice.

Acting upon a dubious-sounding tip about an exclusive interview with a Brown family member, McBride followed Brown’s trail back to its starting point, in Barnwell County, South Carolina, where the New York–born author discovered another, larger enigma: the South that spawned and shaped him. Could one man really consider Strom Thurmond a surrogate grandfather and Al Sharpton a surrogate son? In the South, yes—though it’s complicated. “You cannot understand Brown without understanding that the land that produced him is a land of masks,” writes McBride. “The people who walk that land, both black and white, wear masks and more masks, then masks beneath those masks.”

Nowhere are these masks more evident than in the legal scuffling over Brown’s estate. The bulk of the estate—valued, at his death, at around $100 million—was earmarked for a trust to help educate poor children. Almost ten years and forty-seven lawsuits later, with the estate essentially drained, not a single penny has gone to help a poor child. “The short answer” for why, McBride writes, “is greed. The long answer is boring, which is how lawyers like it.” McBride navigates the case with finesse, offering a convincing argument that Brown’s former manager David Cannon, who served a prison sentence for allegedly mishandling the estate, was wrongfully accused. It’s hard not to smolder along with McBride.

It’s not surprising, however, that Brown’s afterlife has been a mess; his life was a mess too. Brown was married four times and fathered at least six children. He was repeatedly arrested for domestic violence and drug possession and infamously led police on a high-speed chase through South Carolina and Georgia in 1988. McBride acknowledges Brown’s flaws and scandals but sifts through them lightly, as symptoms of a larger pathology that extended beyond Brown himself. Brown was “a terrible person at times,” he writes, “in part because he was afraid of the very world from which his music emerged.”

Keeping that fear at bay meant hiding his essential self. James Brown didn’t hang out after his performances—he killed his audiences, then left them. “You did not get to know James Brown,” McBride quotes a longtime insider, “because he did not want to be known.” McBride gets us closer than anyone else has—close enough to feel the voltage from twentieth-century music’s most electrifying showman.