Willa Cather once wrote that the “heart of another is a dark forest, always, no matter how close it has been to one’s own.” To be honest with you, this is how I feel about my spaniel mix, Betsy, who seems to possess a personal agenda that reaches beyond the dog basics of sleeping and eating. It looms large in her kind, amber eyes, eyes that are just as capable of staring into your soul as they are scanning the horizon for another calling. Betsy—a likely cross between a Brittany spaniel and a King Charles—is a dutiful dog. Only, her sense of duty is her own. Despite living with four other dogs on our farm, she works, and often eats, alone.

It is not appropriate to say that Betsy “came into our lives.” Rather, we forced the issue in what might loosely be termed an ethical dognapping.

My husband, Bo, and I were living in downtown Raleigh at the time, having defected from a year in Washington, D.C. It felt like a homecoming for me, after growing up in the nearby town of Rocky Mount. We were full of determination, ideas, and youthful exuberance, sitting on the couch at night, plotting how he could become a veterinarian like his parents, and I a writer. We lived in a skinny white Victorian on a one-way, not-so-good street, shaded by a large pecan tree.

Within two weeks of moving to North Carolina we had already acquired two rescue dogs: Captain Nemo, a black shepherd mix with melancholy eyes, and Monsieur Scooty Beags, a dysfunctional beagle who had countless phobias—thunder, car rides, manhole covers. At night we walked them down uneven sidewalks and past the historic governor’s mansion, old-school biscuit joints, and abandoned housing projects, all the while dreaming of future animal clinics and novels underneath the streetlights.

Bo took an entry-level job at a veterinary hospital, a job so entry level that it was closer to volunteer than employee. He used his college education to clean cages better than anyone had cleaned cages before, and in this work came across a young dog who had been relegated to a cage in the back. She was chestnut brown and had blonde eyebrow markings above her yellow eyes, a fluffy white tail, and white tufts on her small feet. Week after week he inquired why such a great young dog was being kept crated; apparently the owner had allergies and had largely abandoned her. A month into his employment, Bo started bringing her home on weekends for exercise. She would sprint up and down the stairs in our Victorian, her nails ripping into the old hardwoods. She was named Britney then, but given it was just past the pop prime of Spears, we renamed her Betsy, hoping it wouldn’t confuse her.

Back then, Betsy was a rabble-rouser, a provocateur, perhaps because for the first part of her life she had been cruelly cage-bound. She urged the sad-eyed Captain Nemo to play, fought desperately with our neighbor’s Boston terrier at the fence line, and permitted the insecure Scooty Beags to sleep curled next to her body—but not without opening one eye and uttering a soft growl. We promptly fell in love with her, and the weekends turned into weeks. Eventually, my husband gave up the cage-cleaning job but kept Betsy.

As he attended veterinary school at NC State, Betsy, Scoots, and Nemo were our pack—always loaded into the back of our Subaru wagon for hikes at Umstead State Park. They (unwittingly) volunteered for veterinary duty; Bo learned to draw blood from these dogs, bandage their legs, palpate their abdomens. In her early years, Betsy once tried (unsuccessfully) to nurse an orphan kitten. She would stand off by herself at the dog park, leering at men in sunglasses. She garnered a reputation for enjoying kitty litter and developed a particular zeal for pregnant women, shadowing me throughout two pregnancies.

Thirteen years later, Bo and I have finally become what we aspired to be on those downtown walks: a veterinarian and a writer. Two daughters now lead the pack, and Scoots and Nemo have passed on, leaving Betsy as the last of the three original dogs that we acquired that first year in Raleigh. She is showing her age. She no longer sprints, and her amber eyes have clouded. She is, we have decided, most likely in her last good year of health, and we have proclaimed it the Year of Betsy. She is first in line for choice scraps and car rides. We extend understanding when she rolls in deer excrement or licks the litter box (bad habits die hard). And each morning we let her go outside to do her “work.”

Betsy, you must understand, went from a life in a cage to a life in the city. Then, seven years ago, we moved to a remote corner of southern Vermont, where she could roam wild and free on my husband’s family farm. Now the tips of her brown coat turn golden from sun exposure. She begs to leave the house first thing in the morning, often so driven to get out that she forgoes breakfast.

What is her work? We aren’t sure. And occasionally it’s intense enough to earn her labels of “manic” and “senile.” But whatever it is, it’s important to her, and she heads outside with a yip, her freckled muzzle to the ground. In the morning it seems as if she may be tracking our free-range chickens. By afternoon, we figure she is possibly tracking herself. But if you saw the sheer enjoyment in her movements, you would feel what I feel: admiration. She is master of her day.

Things I appreciate about Betsy in her later years: She speaks her mind. She’s discerning with her affection, but never vicious. She doesn’t walk; she shuffles, but keeps a brisk pace when headed uphill. She has an oddly put-together body, a well-built barrel chest and spindly legs. She knows how to say “please” using her eyes. She likes sunbathing and often looks like she’s happily melting into the driveway on summer days. She picks up odd things in her fluffy tail: burs, pollen, seeds, corn silks, large tree limbs. But what I most admire is her bravery.

Though small, she is the first to respond to new people on the property, to the UPS man’s chagrin. She never bites, but follows, training her intense yellow eyes on perceived intruders. Once on a hike with Bo’s parents in Vermont on Christmas, we let her off leash, only to lose her for an hour in the snow. Later, we found her standing at the precarious top of an iced-over waterfall.

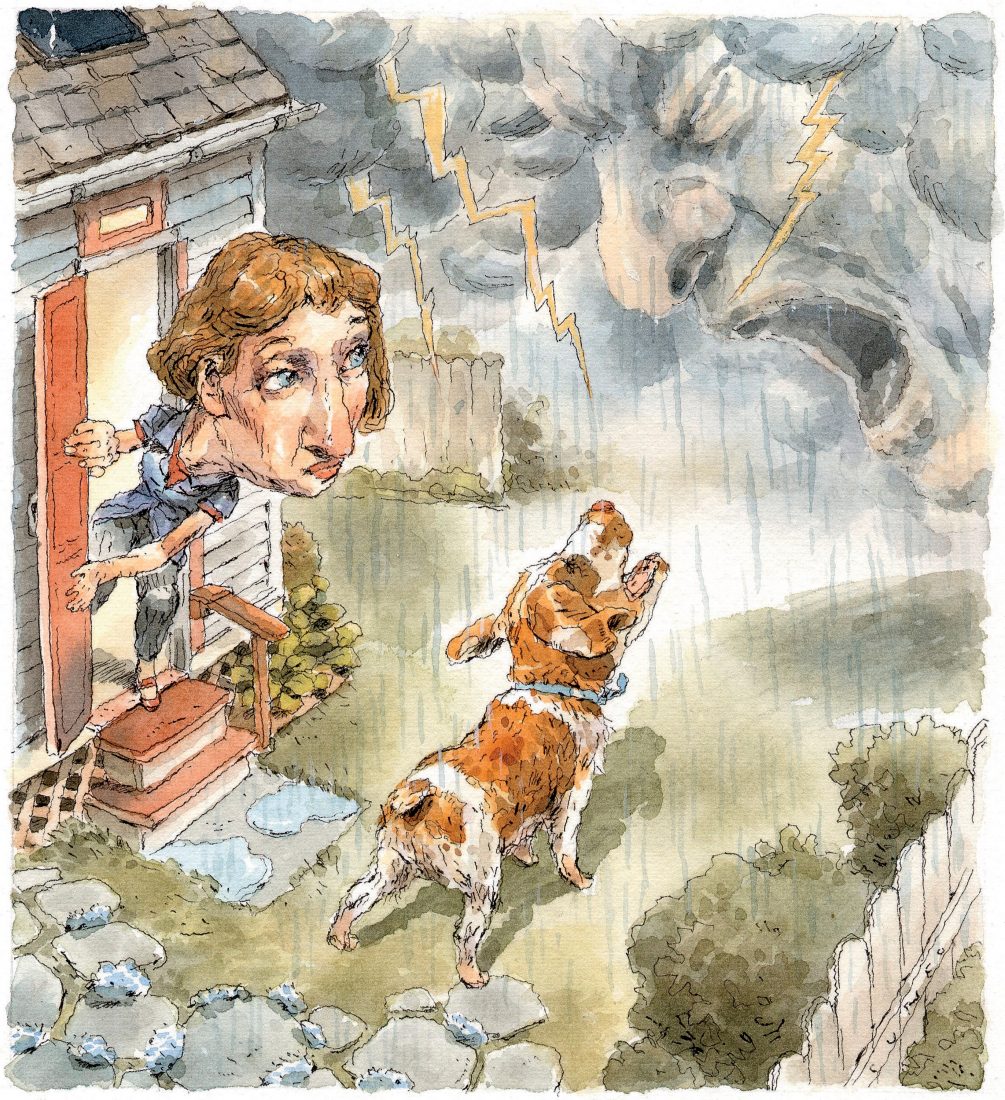

During a biblical thunderstorm in Raleigh one evening—the kind where the sky went dark green and high winds blew pecans into the side of our house like shrapnel—Betsy let herself out the dog door. The other dogs were hiding in their beds. I went to the window to watch as Betsy, trembling a little herself, began barking back at the thunder, a small, solitary dog in the middle of a muddy backyard.

Her bold, dutiful gesture reminded me of Faulkner’s passage about a hunting dog in my favorite short story, “The Bear.” The dog had approached a nearly mythical bear and tried to tree him, coming home worse for the wear. “Put off as long as she could having to be brave,” Faulkner writes, “knowing all the time that sooner or later she would have to be brave to keep on living with herself.”

I don’t know what Betsy does on her own time, these mornings of devoted work, only that she doesn’t need a pack to accomplish it. She never has. Betsy has always been a big dog in a small dog’s body. Above all, she possesses great dignity, and throughout this last good year, we intend to honor it.