Most of the time, comparing printed song lyrics with poems is like comparing recipes with food: that’s to say, patently unfair. Poems, unlike songs, are written to be read, and thus come equipped with their own rhythms and melodies; they’re self-contained entities, the whole shebang. Songs, in contrast, are written to be sung, and what the singing voice can do to words is akin to what a cook can do to raw ingredients: season, char, simmer, sauce, etc. A banal poem is never more than a banal poem. A banal or trite lyric, however, can be—with the right vocal cords—brilliantly and shatteringly conveyed. (Proof of this: much of Frank Sinatra’s output, and the career of George Jones.) Anyone who’s ever read the lyrics of an already cherished song has most likely encountered that hollow sensation of something missing, the absence of certain emotional integers. It can be like viewing a loved one’s X-rays.

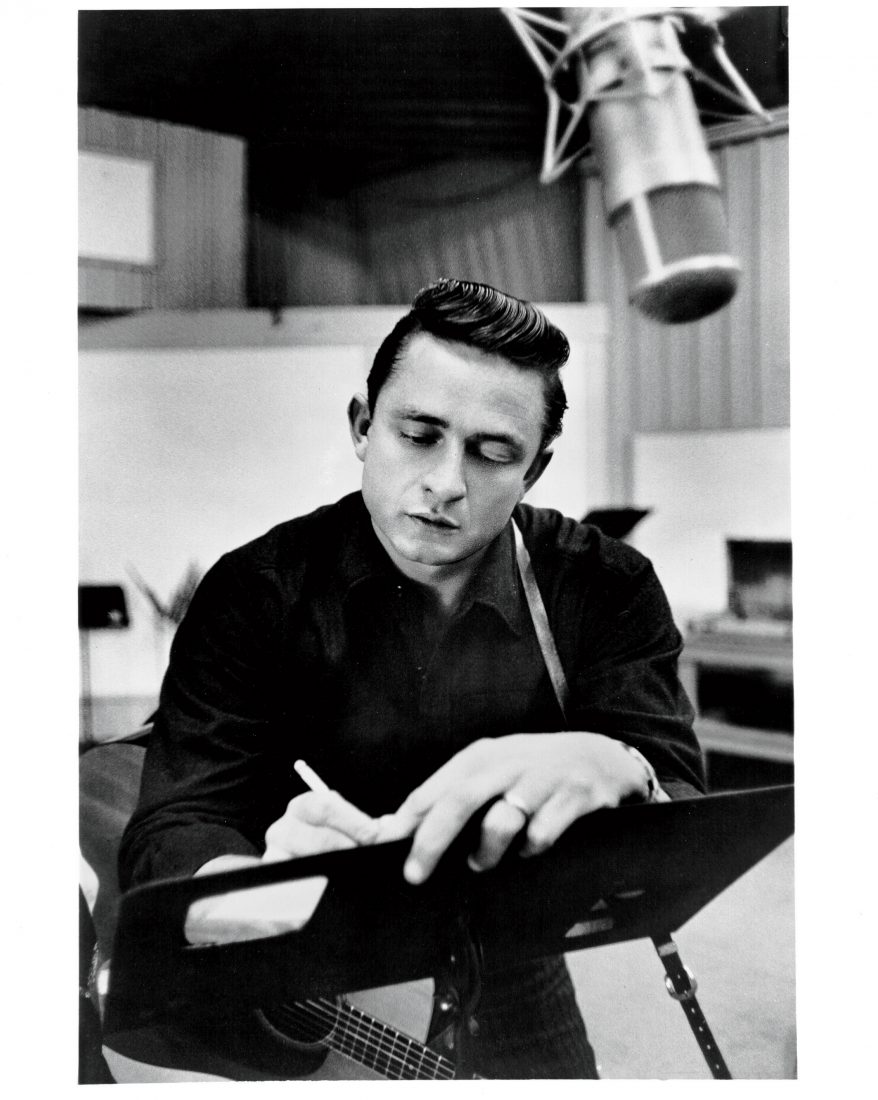

Hence this reader’s initial apprehension at the arrival of Forever Words, a collection of lyrics and poems from the late and very great Johnny Cash (1932–2003). Cash was a deft, canny songwriter (“I Walk the Line”; “Folsom Prison Blues”) whose minimalist lyrics and boom-chicka-boom guitar often masked a wily complexity (each verse of “I Walk the Line,” for instance, is in a different key, with the vocal melody ranging across two octaves). But the songs have always seemed inextricable from the voice: that unmistakable brimstone baritone, hauntingly resonant and immaculately balanced between Saturday-night tough and Sunday-morning tender. Few if any singers covering “Folsom Prison Blues” have left audiences believing that they might’ve shot a man in Reno just to watch him die; when Cash delivered that line, however, you bought it. The gunpowder was there in his voice.

Hence this reader’s initial apprehension at the arrival of Forever Words, a collection of lyrics and poems from the late and very great Johnny Cash (1932–2003). Cash was a deft, canny songwriter (“I Walk the Line”; “Folsom Prison Blues”) whose minimalist lyrics and boom-chicka-boom guitar often masked a wily complexity (each verse of “I Walk the Line,” for instance, is in a different key, with the vocal melody ranging across two octaves). But the songs have always seemed inextricable from the voice: that unmistakable brimstone baritone, hauntingly resonant and immaculately balanced between Saturday-night tough and Sunday-morning tender. Few if any singers covering “Folsom Prison Blues” have left audiences believing that they might’ve shot a man in Reno just to watch him die; when Cash delivered that line, however, you bought it. The gunpowder was there in his voice.

But it was also, as Forever Words more than demonstrates, in his pen. “My dad was a poet,” his son, John Carter Cash, writes in the book’s foreword, who “saw the world through unique glasses, with simplicity, spirituality, and humor.” These qualities are evident in the forty-one pieces gathered here—selected and introduced by the Pulitzer Prize–winning Irish poet Paul Muldoon—ranging from unrecorded song lyrics to a versified retelling of the book of Job to straight-up poems. “I Heard on the News,” about Vietnam, offers echoes of Frank O’Hara in its construction and W. S. Merwin in its acid take on the cosmic absurdity of war; but it stands on its own, without the sound of Cash’s voice, a glinting shiv of a poem whose edge is derived from its content, not its byline.

Familiar figures wander through many of the other poems and ballads, the Americana icons that Cash helped create: a long-haul trucker rumbling toward his woman; a gold prospector in Alaska; a soldier named Johnny a-heading off to war; a poor boy in love with a wealthy captain’s daughter. But there are surprises, too, as in Cash’s private 1980s rewrite of his 1958 hit “Don’t Take Your Guns to Town.” In the original version, a reckless young cowboy named Billy Joe ignores his mother’s advice to leave his guns behind, and ends up shot in a saloon. In Cash’s later version, Billy Joe is now Joe, a disaffected “young man of propriety” and would-be assassin whose girlfriend dissuades him from gunning down celebrities. It’s the same story, but with the mythology of the fifties giving way to the sociopathology of the John Hinckley, Jr., era, Cash’s ear tuned to the nation’s tonal shifts.

The most fascinating figure in the book, of course, cannot help but be Johnny Cash himself, and he’s here in big doses. “Don’t Make a Movie about Me,” written in 1982, is a playful rebuke to those wanting to dramatize his unruly outlaw life.

Truth, said the Master, cannot be hid

But he didn’t say slap it in the face of my kids.

A stone is a stone and forever stone

But I’m part good and bad and then I’m gone.

Elsewhere, in just two pages, “Going, Going, Gone” presents as vivid and desolate a portrait of addiction as a shelf full of memoirs. It’s difficult not to see June Carter Cash, his wife of thirty-five years, faintly blushing at the end of the many love poems included herein. And it’s hard not to choke up a bit, and not to register the enduring truth of the close of the poem “Forever,” written just before Cash’s death in 2003:

You tell me that I must perish

Like the flowers that I cherish

Nothing remaining of my name

Nothing remembered of my fame

But the trees that I planted

Still are young

The songs I sang

Will still be sung.