Robert Harling grew up in Natchitoches, Louisiana, and lost his sister and “best friend” to diabetes in 1985. He turned the experience into the iconic stage play Steel Magnolias, which is still performed all over the world. The subsequent movie launched Harling’s career as a screenwriter, and since then he’s written Soapdish and The First Wives Club, among other hits. On the occasion of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the play’s production, he talks about how it all began.

You graduated from Tulane’s law school. When did you realize you wouldn’t be hanging out at the courthouse all day?

I knew almost after my first week of class that I’d never inflict myself on the world as a lawyer. But I stuck with it and graduated because I loved Tulane, the people, and I had a job as a singer for a big band that played all the swell gigs in New Orleans. It was a great life.

By the time you wrote Steel Magnolias, in 1987, you were living on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. What were you doing for a living?

I was an actor. Auditioning lots, getting little. I did some commercials and voice-overs. And I had a job selling tickets for Broadway shows. Not the most exciting existence.

How long did the play take you to write?

It was written in about ten days. The events that inspired it were so powerful that, after I found the story arena, it just poured out into my typewriter in a 24/7 tsunami of Southernness. I had no idea what I’d written. I asked the first person I gave it to if it even looked like a play. I wasn’t really sure. All I knew was that I felt it portrayed my sister’s life and spirit accurately, and that was enough for me.

The play was an instant hit off-Broadway, and almost immediately you were asked to adapt it into a screenplay for the 1989 movie.

It happened so quickly. With the buzz around the play in New York, there was a constant stream from Hollywood coming to check it out. Ray Stark bought the rights and promised me he’d film it in my hometown of Natchitoches, which really clinched the deal. Almost every actress in the biz came to the theater to see it. They had to shut down the street the night Elizabeth Taylor came, the crowds were so large. I had tea with Bette Davis, who wanted to play

Ouiser. The movie had premieres in Los Angeles, Atlanta, New York, and Natchitoches. That was a surreal week. The New York premiere was amazing. Ray wanted the biggest premiere party since The

Godfather, and he got it. It was at the Hilton. They re-created the wedding set from the

movie. I remember watching my dad in deep conversation with people like Walter Cronkite…I pinched myself a lot those days.

How many countries has the play been performed in, and what are the differences in the productions?

I know of seventeen authorized translations. I’m sure there are more. I’ve seen it in Japanese, Chinese, French, Swedish, Spanish, Italian. But it’s become clear to me: Beauty shops are universal. Demonstrating the need for friendship and support knows no bounds. The main variable is the set. Some of the foreign notions of what a converted Southern carport looks like are mind-blowing. And there was one Italian production where every character was hot. Even the two older characters of Ouiser and Clairee. Smoking hot. The play still worked!

I can only imagine the impact on Natchitoches when the movie crew—everyone from director Herbert Ross and his then girlfriend Lee Radziwill to Dolly Parton and Sam Shepard—descended.

Shooting it in Natchitoches was beyond. While I was hanging out with Sam, one of my idols, he pointed out to me what a singular experience it was to write a play about my family and then have it become a movie filmed in the town where it happened, in the houses and churches with the family and friends who inspired it in the background. The town went nuts in the summer of ’88. The biggest stars in the world were squeezing vegetables in the Winn-

Dixie. Word spread like lightning about their every move. Olympia Dukakis’s cousin Mike was running for president, so die-hard Republicans across the street from where she was living put Dukakis signs in their yards to be neighborly. Princess Radziwill loved it there. She and Herbert got engaged during the shoot. Julia [Roberts] bowled at the bowling alley. Dolly and I drove around all the drive-ups in search of the best fried okra.

Where did the cast stay—and eat? Did your mother make her amazing coconut cake?

All the stars rented homes in the area. Tom Skerritt (who played my movie dad) lived next door to my real dad. Again, how often does that happen to a writer? We had a lot of cookouts and potluck suppers. The inspiration for Soapdish, my second film, came from one such dinner when Sally [Field] said, “I’ve always wanted to play a bitch who gets to wear nice clothes.” That simple thought birthed a huge idea. And yes, Mama was churning out her coconut cakes as

fast as she could. There was always one on the counter,

one in the oven, and at least one in the freezer.

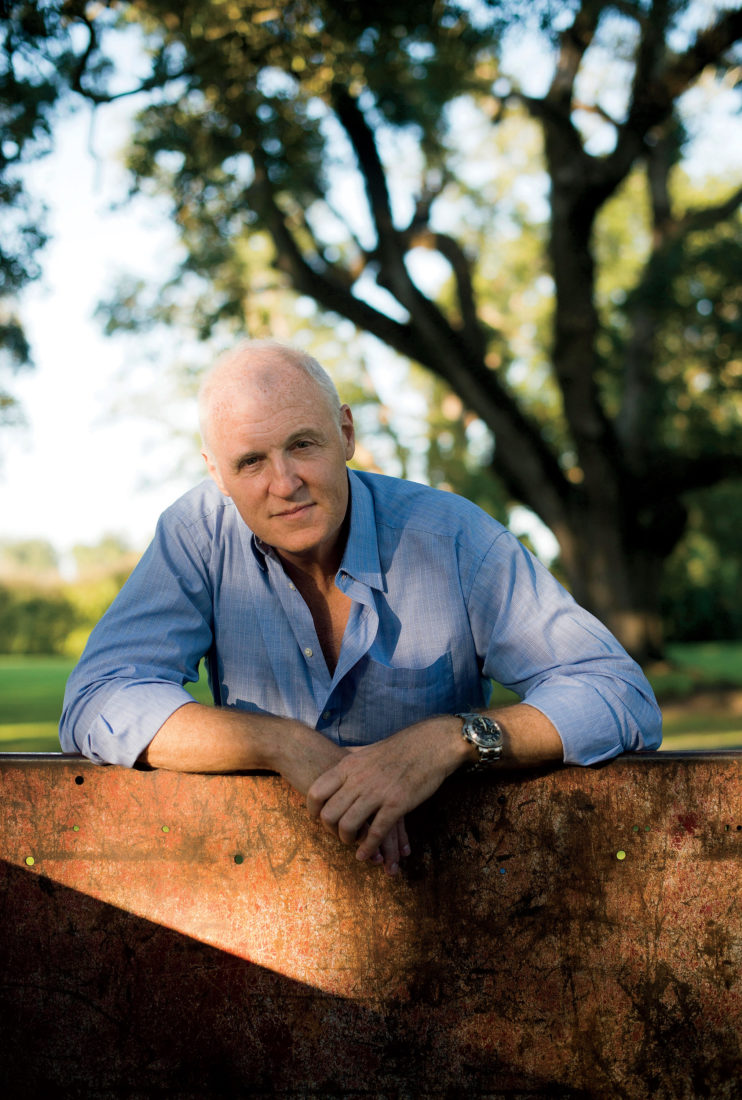

Photo: Rush Jagoe

Delta Son

Harling takes a drive around his property on the banks of the Cane River.

Speaking of cake, had you ever seen an armadillo groom’s cake?

There was indeed an armadillo groom’s cake at my sister’s wedding. The red velvet part was my writerly creation.

The original one was very simple—a sheet cake cut in the shape of an armadillo. Not like the high art form it’s become. I’ve seen some amazing edible armadillos. The New York Times credited me with the rediscovery and revival of

red velvet cake. I consider

this as one of my great life achievements.

There are so many quotable lines it’s impossible to count them. Do you have a favorite?

The one that still makes me laugh the most is when Truvy says of her wayward son, “I should’ve known Louie had problems when his imaginary playmates wouldn’t play with him.” That’s my kind of humor. And when speaking

of Louie’s girlfriend, “The nicest thing I can say about her

is that all her tattoos are spelled correctly.”

Tell us what the title

means to you.

When I was a kid, a lady in the neighborhood had a large metal floral paperweight on her kitchen counter that served as a receptacle for change, keys…it weighed down the check for the milkman or the dry cleaner receipt (not that you’d ever need a dry cleaner receipt in my small town—everybody knew who a dress belonged to), whatever. She called that thing on her counter “the steel magnolia.” In her sweet drawl, she’d say, “Take a quarter from the steel magnolia and get us some ice cream.” I found it interesting that the thing was neither steel nor a magnolia, but that’s what she called it. And the imagery stuck. Something beautiful made of very strong stuff.

When I was young, often sent to pluck a few magnolia blossoms for my mama’s floral needs, I learned that, while gorgeous, they are fragile and bruise easily—qualities often attributed to Southern women. My extraordinary life experiences with my sister and mother showed me that the women I’ve known are indeed gorgeous, but their lives can be fragile. But if you look underneath, you realize they possess a tensile strength stronger than anything I could ever muster. I wrote of their strength, joy, and laughter that rang out no matter what life threw at them. After my sister’s death, the only way I could deal with it was to celebrate them. When the play was finished, I needed a title. In my head, I heard that grand dame’s voice and the way she pronounced “steel magnolya.” It seemed right. My mother, my sister, my aunts, the neighbor ladies—I still hear their glorious voices all the time. I hope I always will.