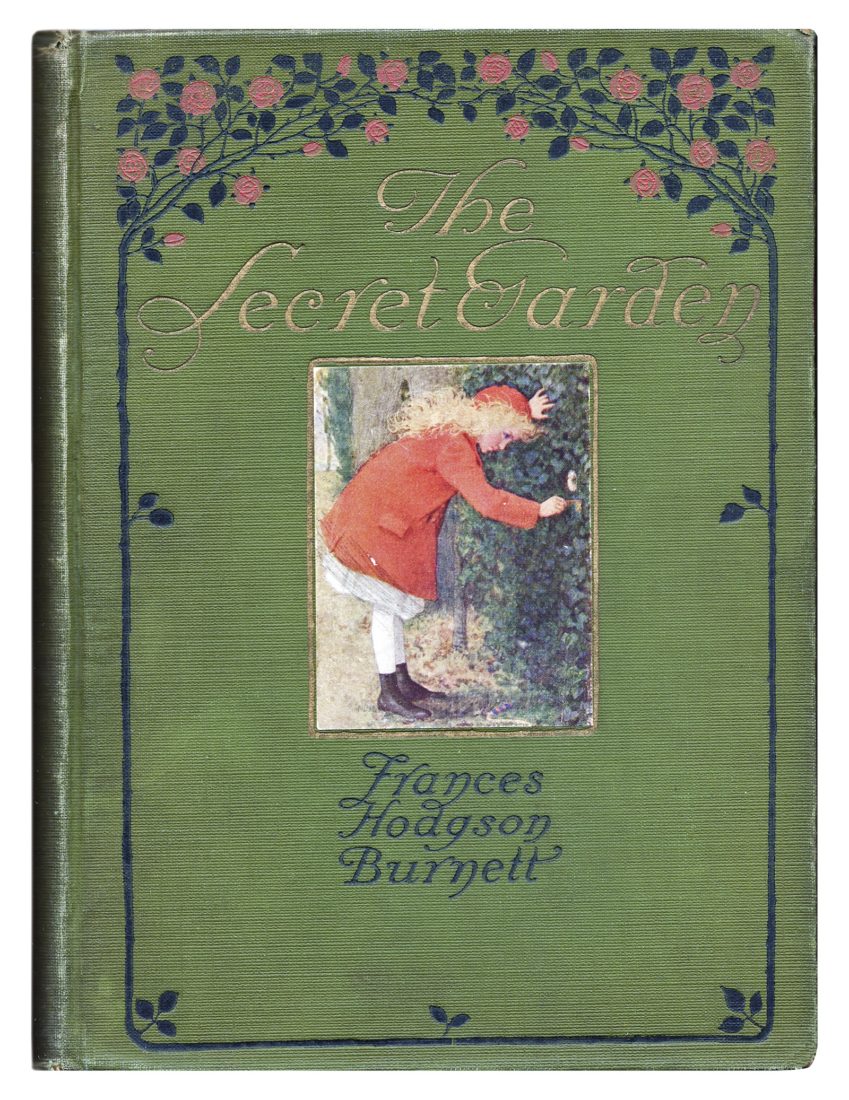

Although The Secret Garden was published more than a century ago, in 1911, the classic children’s book—and its multiple film and television adaptations—continues to captivate readers young and old. “There’s something about The Secret Garden that strikes a chord deep within us, because I think a lot of people share that experience of awakening, either in their garden, or outside,” says Marta McDowell, the author of the fascinating and recently published book Unearthing the Secret Garden: The Plants & Places That Inspired Frances Hodgson Burnett.

And even though the author, Frances Hodgson Burnett, was born in England and set most of her novel there, she drew inspiration for her writing life from the plants and landscapes she encountered throughout her travels—including to Bermuda, where she tended a garden later in life, and in the American South, where she found her footing as a young writer.

Frances Hodgson was born in 1849 near Manchester, England, and her father died unexpectedly just four years later. In 1865, Hodgson’s widowed mother moved the family closer to her own brother in East Tennessee near Knoxville. “Kind neighbors stopped in with extra food to help these genteel, impoverished Englishwomen transplanted to the Tennessee hills,” McDowell writes in her book.

Although the family barely scraped by financially, the time was creatively abundant for the teenaged Frances, who later remembered climbing hills and wandering woods “where one gathered things, and sniffed the air like some little wild animal,” who inhaled “the odor of warm pines and cedars and fresh damp mould, and pungent aromatic things in the tall ‘Sage grass.’”

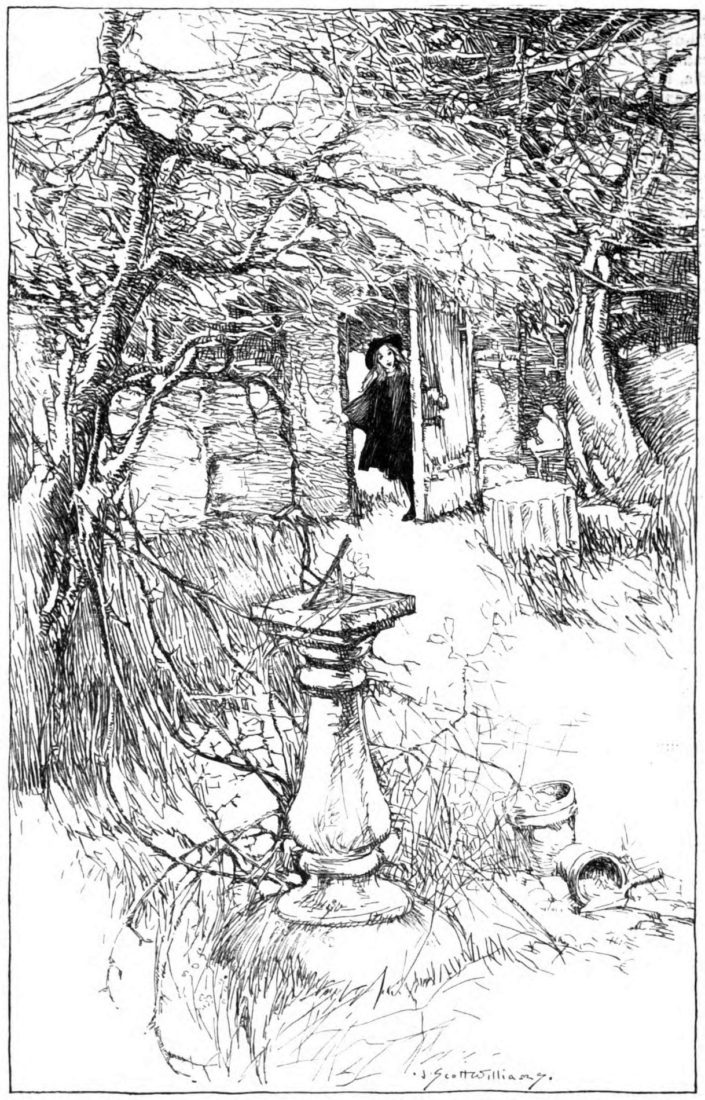

Just past a sassafras thicket near her home, wild grapevines crowned a meadow. “She called this wooded glen her Bower,” McDowell says. “She needed a space for writing, so she carved her own spot out in the woods. With the grapevines growing over it, it had the fort-like feeling of a secret garden. It was here that Frances moved into adulthood, learned the importance of her own space, and really began to write.”

Frances collected wild grapes from the Bower, and with her two sisters sold them at the local market to pay for paper and postage to mail her stories to editors. By 1868, Godey’s Lady’s Book published her story “Hearts and Diamonds.” At age nineteen, from her grape glen in the Tennessee hills, one of the world’s most beloved authors got her start.

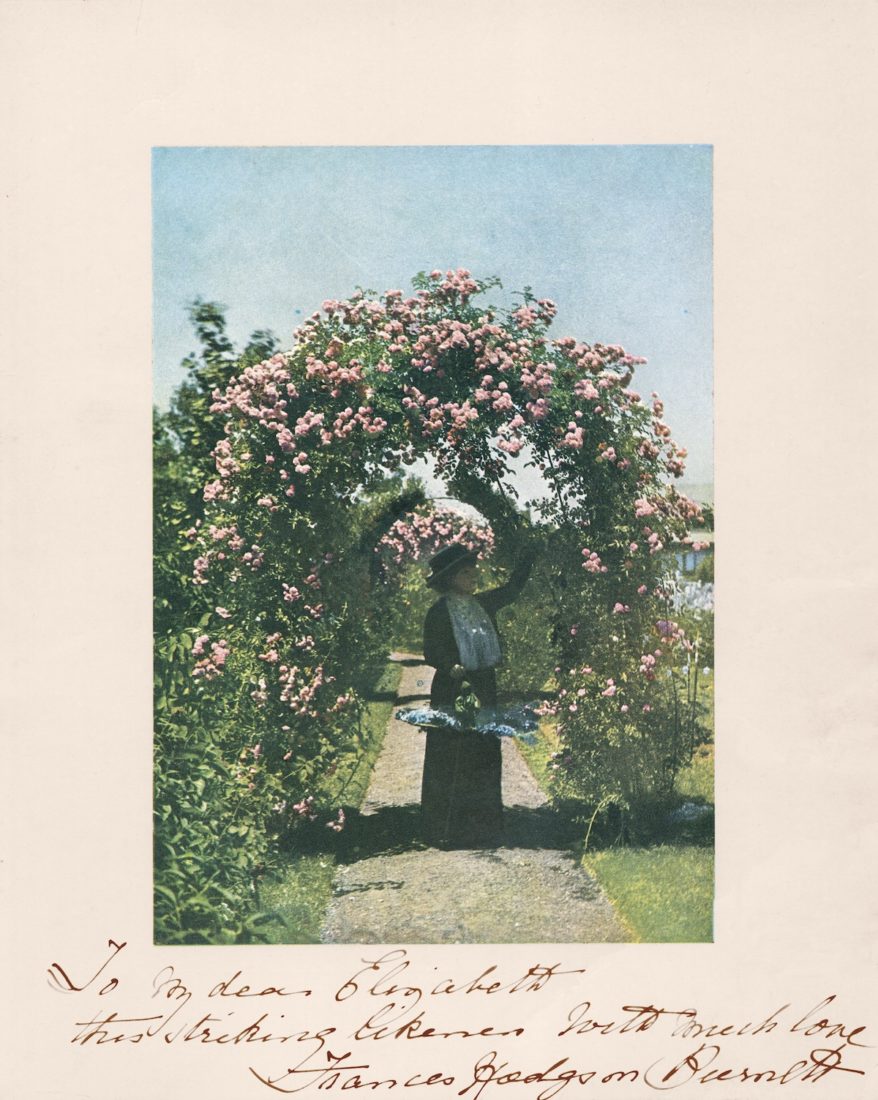

The rest of McDowell’s delightful book shares more secrets behind Frances’s writings, and her moves to England and throughout the United States—but one detail stands out. Frances herself was a late-blooming gardener. She only started gardening seriously when she was nearly fifty. “Like anyone who picks up an avocation later in life, you kind of always feel like you’re an amateur,” McDowell says. “Frances got a late start in gardening, but she always encouraged people to just try.”

Her favorite getaway probably felt a bit like some of her childhood memories—Bermuda, the British island territory in the Atlantic, whose closest neighbor is the coast of North Carolina. In the early 1900s, Frances stayed each winter at a Bermudan bungalow called Clifton Heights.

At the charming cottage, with the help of a few local workers, she planted roses, pink and white petunias, red poppies, yellow coreopsis, and bright and bold crotons. She grew many varieties of hibiscus, the one flower she mentioned by name in the first chapter of The Secret Garden, which opens in India. “Now she could grow [hibiscus] in her own garden,” McDowell writes. “It seemed like a fairy dream.”

By this time a quite successful author working on The Secret Garden’s film rights, Frances became a bit plant obsessed. One funny tale from her time in Bermuda, as McDowell explains in the book: Frances faced a roadblock while trying to make her way home. When she sent her driver to check on the hold up, “he returned to inform her that the convoy was her plant order, making its way by heavy cartloads from the nursery to Clifton Heights.”

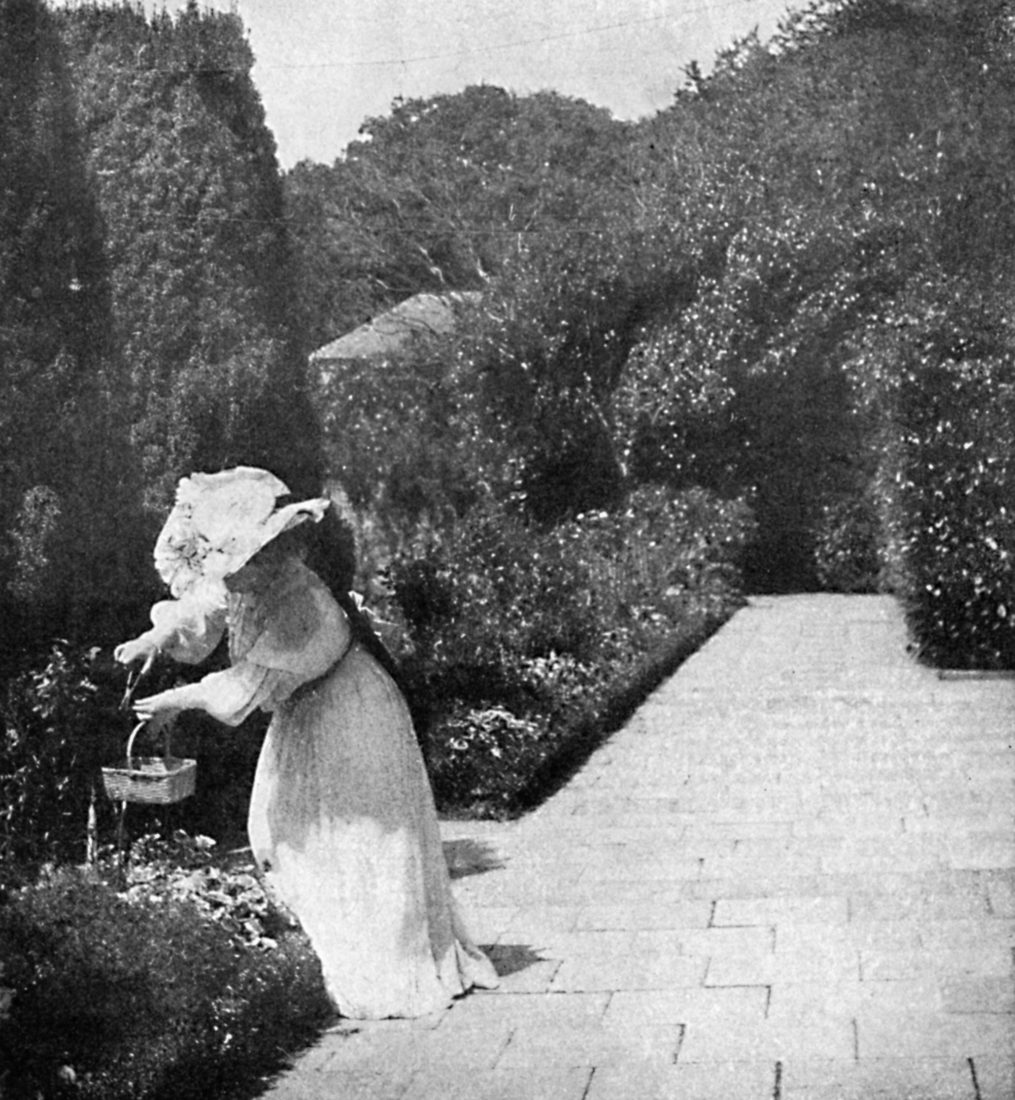

Frances Hodgson Burnett gardened there for the last time in 1921 (she died in New York three years later), and according to Bermudan locals, some of the roses she planted still bloom at Clifton Heights—a private home—today. Her Bermuda garden was, for a decade, a fruitful place for the author to write and reset. “She made a practice of writing in the morning, sitting indoors at her desk with pen in hand while the garden tempted her,” McDowell writes of the perch where Frances sat overlooking dark green elephant ears, sunny marigolds, and ruby amaryllis. “Such dedication is the trial of every writer who gardens.”