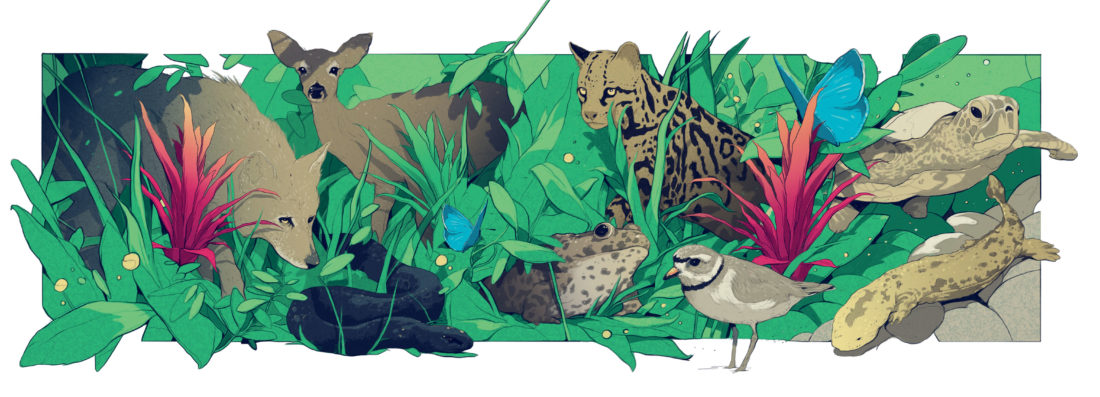

Unforgettable creatures, from the Texas ocelot to the Ozark hellbender, have historically thrived in the South thanks to the region’s rich biodiversity, a quality that has in turn attracted an influx of new residents and development that now imperil their very existence. In fact, these factors and others, says Jaclyn Lopez, the Florida director and senior attorney at the Center for Biological Diversity, have led in part to the South’s becoming home to more endangered and threatened species than anywhere else in the country. Here, a sampling of animals at risk of being lost forever.

Red Wolf

Canis rufus

Population: 14

Traits: The tawny canines resemble coyotes.

Range: The remaining wild wolves live on North Carolina’s Albemarle Peninsula.

What Happened: Predator control programs practically stamped them out by the 1960s.

Reason for Hope: A successful captive breeding program begun in the 1970s has resulted in around 200 additional red wolves living in captivity today.

Eastern Indigo Snake

Drymarchon couperi

Population: UNKNOWN

Traits: This nonvenomous iridescent blue-black species is the longest native snake in North America.

Range: Florida, and the coastal plain of southern Georgia (but range once included southernmost Alabama and southeastern Mississippi)

What Happened: The species all but disappeared due to longleaf pine forest destruction (but when a researcher does come upon a snake, he or she gets to name it).

Reason for Hope: South Georgia’s Orianne Indigo Snake Preserve provides a crucial habitat; biologists recently found the first baby indigo in Alabama in sixty-plus years, thanks to reintroduction efforts.

Florida Key Deer

Odocoileus virginianus clavium

Population: <1,000

Traits: A subspecies of the North American white-tailed deer, the herbivore is roughly the size of a large dog.

Range: Only in the Lower Florida Keys

What Happened: Habitat destruction and poaching nearly wiped them out by the 1950s; lately, screwworm infestations have depleted numbers.

Reason for Hope: A recently installed chain-link fence along U.S. 1 on Big Pine Key protects the herd from being hit by cars.

Dusky Gopher Frog

Rana sevosa

Population: 100

Traits: The dark-spotted species (one of the world’s one hundred most endangered) often uses gopher tortoise burrows.

Range: Harrison County, Mississippi (down from a range that once included southeastern Louisiana, southern Mississippi, and southwestern Alabama)

What Happened: Habitat loss of longleaf pine forests and destruction of ephemeral ponds used as mating locations

Reason for Hope: The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s 2015 Recovery Plan for the Dusky Gopher Frog has established specific goals, strategies, and actions to help the species rally.

Texas Ocelot

Leopardus pardalis albescens

Population: 60

Traits: This feline with leopard-esque spots is twice the size of an average house cat.

Range: Texas and Mexico (but once ranged east to Arkansas and Louisiana)

What Happened: Habitat loss from farm and highway expansions; future threats include the wall in progress at the Mexican border, which could hinder breeding.

Reason for Hope: The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is working to install corridors that mitigate the ocelots’ need to cross highways; car strikes are the greatest current threat to the species.

Piping Plover

Charadrius melodus

Population: 1,372 pairs

Traits: The shorebirds—numbered here by the breeding pairs of the Atlantic coast population—have black-banded necks.

Range: During breeding season, from Newfoundland to North Carolina; in winter, on the coast from North Carolina to Florida, down to the West Indies

What Happened: Feather hunting caused their decline in the 1980s; now, beachfront development on preferred nesting grounds has diminished the species.

Reason for Hope: Towns such as Hilton Head, South Carolina, monitor winter roosting areas and assist the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service with surveys; the FWS has also restricted access to nesting areas.

Miami Blue Butterfly

Cyclargus thomasi bethunbakeri

Population: <50

Traits: The males of the tiny, delicate insects have bright blue wings; the females, gray.

Range: Bahia Honda State Park, on Florida’s Big Pine Key

What Happened: Hurricane Andrew decimated a whole population in 1992, leaving only Bahia Honda’s; habitat loss due to development threatens that group.

Reason for Hope: Captive numbers recently increased thanks to the Florida Museum of Natural History’s breeding program.

Ozark Hellbender

Cryptobranchus alleganiensis

Population: UNKNOWN

Traits: The flat aquatic salamanders can grow up to two feet long and can survive up to thirty years in the wild.

Range: The White River watershed in Arkansas and Missouri

What Happened: Habitat degradation due to ore and gravel mining, sedimentation, and nutrient and toxic runoff

Reason for Hope: The Ozark Hellbender Working Group put together a watershed protection plan; in the last decade, the Saint Louis Zoo has cultivated a first-of-its-kind captive breeding program.

Kemp’s Ridley Sea Turtle

Lepidochelys kempii

Population: 7,000–9,000

Traits: The world’s most endangered sea turtle is also its smallest, at twenty-three to twenty-seven inches long.

Range: Mostly along the Gulf of Mexico, and the coasts of South Carolina and Georgia

What Happened: Historically, humans hunting for their meat and eggs; today, bottom trawling and gillnet fishing

Reason for Hope: Changes to and regulation of fishing practices and gear modifications, as well as nest protection, have boosted numbers.