Every family has its secrets—a recipe or fishing spot, perhaps. But for the storied Bingham family, of Louisville, Kentucky, the secrets could fill volumes. And, for more than a century, they have. In the 1980s, the power struggle that resulted in the dismantling of the family’s media empire, which included the Louisville Courier-Journal, was the topic of countless newspaper and magazine stories, even books. In 1917, the subject was even more sensational: the death of Mary Lily Kenan Flagler, the second wife of family patriarch Robert Worth Bingham, who launched the family to fame and fortune with her Standard Oil inheritance. Kenan’s body was exhumed by members of her family to test for evidence of poison. “MRS. BINGHAM WAS DRUGGED,” a tabloid headline screamed.

But even in the midst of such salacious stories, the family blotted out all mention of the one-time heir, Henrietta Bingham. Writer and historian Emily Bingham had heard only whispers about her great-aunt—a larger-than-life figure in the vein of Tallulah Bankhead or Zelda Fitzgerald. When Emily began exploring her family’s past, she couldn’t deny the pull of the mystery. After one fateful discovery, she began piecing together Henrietta’s story. The result is Irrepressible: The Jazz Age Life of Henrietta Bingham, released in June.

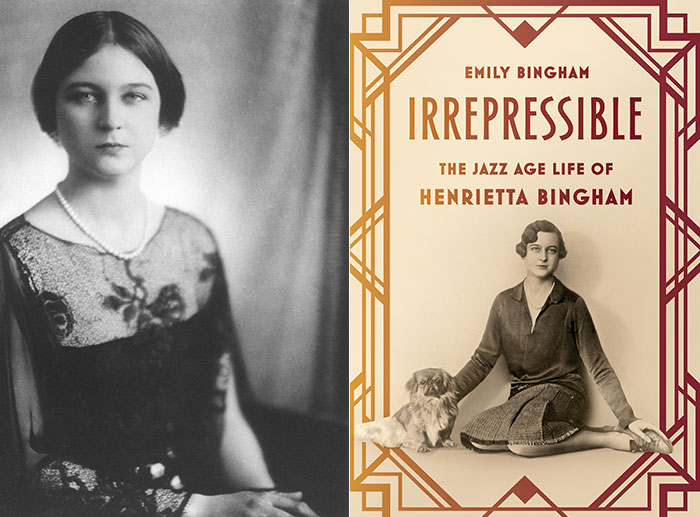

Photo: All photos courtesy Emily Bingham

From left: Henrietta Bingham posed for a portrait in London in 1923; Irrepressible: The Jazz Age Life of Henrietta Bingham

From the book’s prologue:

Born in 1901, [Henrietta] came of age amid tragedy and enormous wealth, and spent much of her twenties and thirties ripping through the Jazz Age like a character in an F. Scott Fitzgerald novel. There were parties, music, great quantities of alcohol, and, on both sides of the Atlantic, lovers—lots of them … Later there would be mental breakdowns, scandals, and a decline no one talked about. Within our family, charity meant silence when it came to Henrietta.

Emily breaks that silence in her book. Here, she shares how she did it.

What was it like to write about your family?

I never wanted to write about my family—that was already a full shelf. I did not have any interest in bringing up the bodies again. All of that was extremely sensational and it left scars. The only reason I took on Henrietta was I was sure she was completely outside of all that. But when I got further into the research, I discovered how close her relationship with her father, Robert Worth Bingham, was. His shame and scandal of the death of his first and second wives created a dependency that was extraordinary to the extent that the whole family has this gothic character.

Henrietta astride her Chestnut Mare, Because. Artist Edward L. Chase used the image for an oil portrait of her in the early 1940s.

What was the family like as Henrietta grew up?

Louisville at the turn of the century was a booming place, bigger than Atlanta and richer than Richmond. After her mother’s death, Henrietta’s father married a great southern debutante figure named Mary Lily Kenan Flagler. Her husband Henry Flagler developed Florida’s east coast, so by marrying her, Bingham catapulted himself into a new position socially and financially. When Mary Lily died, Bingham got this surprise bequest from her of $5 million. Her family was upset—you know, wills.

Bingham’s new wealth enabled him to wield a whole different level of power in Kentucky. The first step was to purchase the Courier-Journal and Louisville Times, which gave him a platform for political reform. The family ownership continued through most of the twentieth century.

Your family rarely spoke about Henrietta. But a 2009 discovery in the attic of the family’s Georgian mansion on the outskirts of Louisville opened up her world to you.

There were two of Henrietta’s trunks in the attic. They had been up there my entire life. It’s a scary weird place to be for an entire day. There’s one light bulb in the attic. So I opened the first trunk, thinking it was just clothes. I start doing painstaking listings of socks and scarfs, riding crops, and disintegrating boas dropping feathers all over everything.

Right before I left I saw that there was another trunk in the corner. It was full of books, old matchbooks with her monogram, and Virginia Woolf first editions. And at the very bottom, a square three feet and up to my armpits, there were neatly stacked letters.

Who wrote the letters?

They were love letters from two men Henrietta nearly married in her twenties in the 1920s. Both of them were fabulously interesting guys, and the language was so dramatic. I read a line, “I can only imagine you surrounded by adorers of every sex,” and I’m like, whoa. There were 150 letters in total, and it took me days and days to go through them. That was a massive find.

How did you learn about her other romances?

I found these tennis clothes including a pair of shorts. They were clearly bespoke, and I took them out and saw the monogram matched the name of a tennis player, Helen Hull Jacobs. I had known from one other source that they knew each other, but to have each other’s clothes in a personal trunk was something else.

I learned Helen was the first woman to wear shorts on the tennis court at Wimbledon and it was scandalous. Women in 1930s were wearing skirts below their knees and stockings, and she said to hell with it. So these are famous shorts. I sent them to the Tennis Hall of Fame in Newport, Rhode Island, and received an acknowledgement from the curator, who said they were glad to have the contribution to their Helen Jacobs collection. It turns out that Helen Jacobs left them all her scrapbooks and diaries, which were full of information about Henrietta.

They met in 1934 and were together through the beginning of World War II. It was an extremely serious and long-term relationship conducted largely in public—quite remarkable at the time. That shaped the arc of the book to have this long-term relationship documented.

Henrietta (center) and friends at the Kentucky Derby in the late 1930s or early 1940s.

Henrietta lived in New York City, England, and eventually moved back to Kentucky. Did moving back South feel like coming home?

A Southern lesson here is the pull of home and how badly Henrietta wanted to be a Kentuckian. She wanted to have a full life here. Before her father died in 1937, he set her up on a farm outside of Louisville in Oldham County. It was a very beautiful farm overlooking the Ohio River and she bred top stallions and brought back the English bloodlines.

Henrietta and hunting companions after a grouse shoot in Scotland in 1927.

Where did she get her interest in sporting?

She started as a little girl, and then as she got older, she competed and then totally caught the fox-hunting bug. It was completely addictive to her. When she was fox hunting, she was at her happiest and healthiest. Her father was an amazing sportsman, and there was a family property— a quail plantation in Georgia she ended up inheriting. The horse interest did morph in a lovely way when she came back to Kentucky in the 30s and became a thoroughbred breeder.

How do you want readers to remember her?

I want her to be seen as somebody who took a lot of risks and was daring in her time. She tried to lead an honest and open life about whom she loved and how she did it. I’m glad she’s getting to have a second coming-out party. I want people to remember that she took her Southern heart with her everywhere she went.