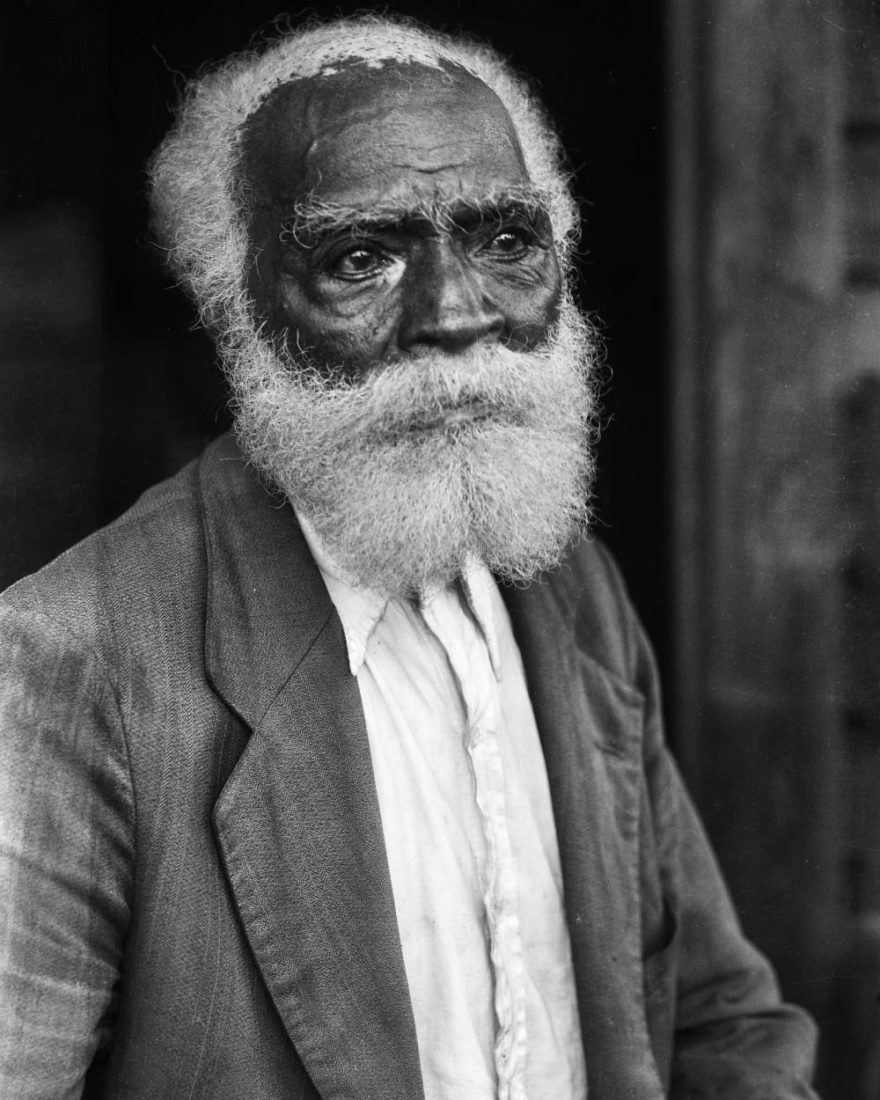

Twenty-five years ago, Jerry Cotten stood in a private cemetery in Little Switzerland, North Carolina, a small mountain town nestled along the Blue Ridge Parkway. The now retired photographic archivist was searching for the grave of Elizabeth Hollifield, a woman featured in one of his favorite photographs. “She projects an image of serenity and strength,” he says. Scrawled in pencil on the back of the portrait is a note: “Last summer I drove by her cabin many times, and she was always sitting in the door, waiting,” Bayard Wootten, the photographer, wrote.

Cotten discovered Wootten’s photographs in the early 1970s when he worked for the North Carolina Collection at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He spent hours sorting through images acquired by the Wilson Special Collections Library, home to the largest assortment of Wootten’s work. Out of approximately 90,000 items, including negatives and prints, the photos of 1930s rural North Carolina caught his attention. “They immediately stood out to me because they were so artistically composed,” he says. “And [they depicted] a world that I was familiar with.” (In the 1950s, Cotten spent his high school summers working on a tobacco farm in Chatham County, North Carolina.) Signed in the corners of some of the images was a name he wasn’t yet familiar with: Bayard Wootten. “The more I investigated her, the more I realized that she was someone who had done some remarkable things with a camera. She was not well known—people had never heard of the woman.”

Wootten, born in the coastal town of New Bern, North Carolina, in 1875, grew to excel in a profession dominated by men. In 1901, her husband abandoned her and their two sons. Determined to support her family, in 1904 she borrowed a camera and taught herself how to take photographs.

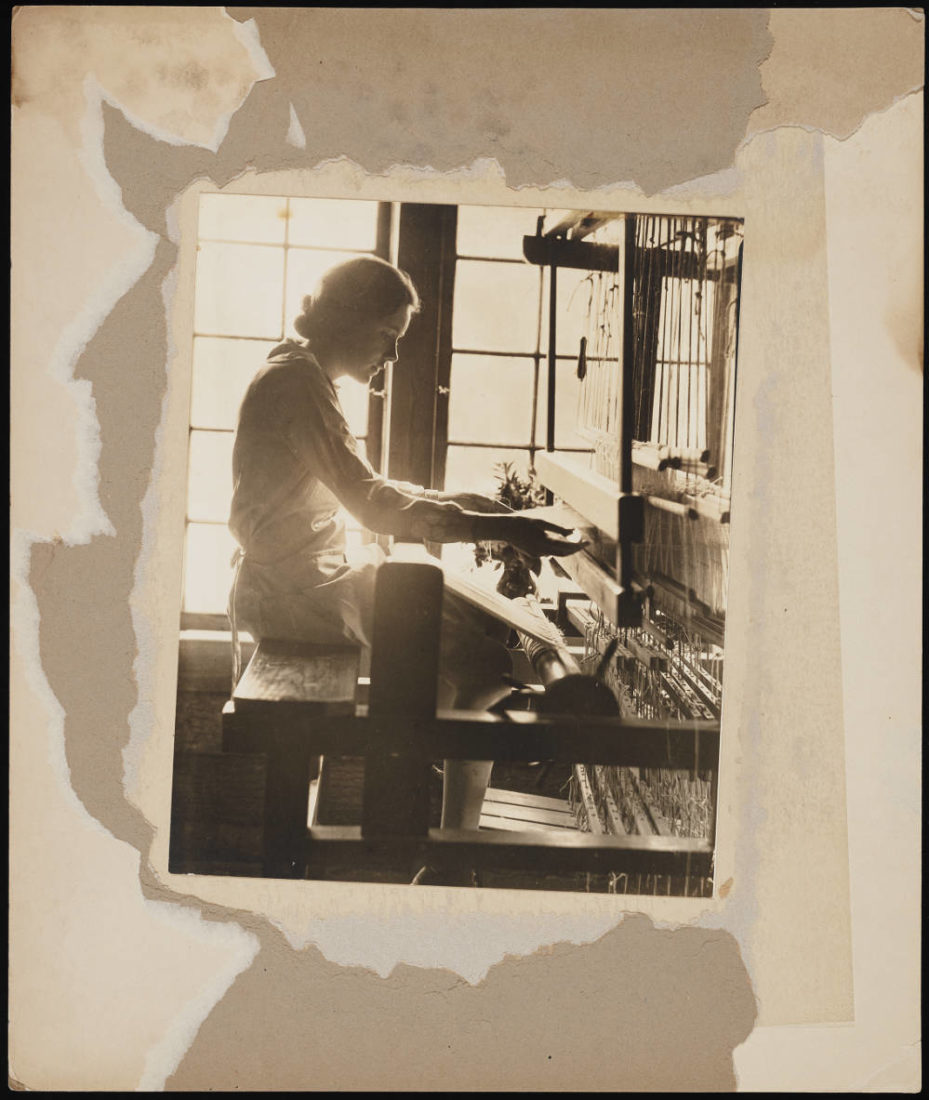

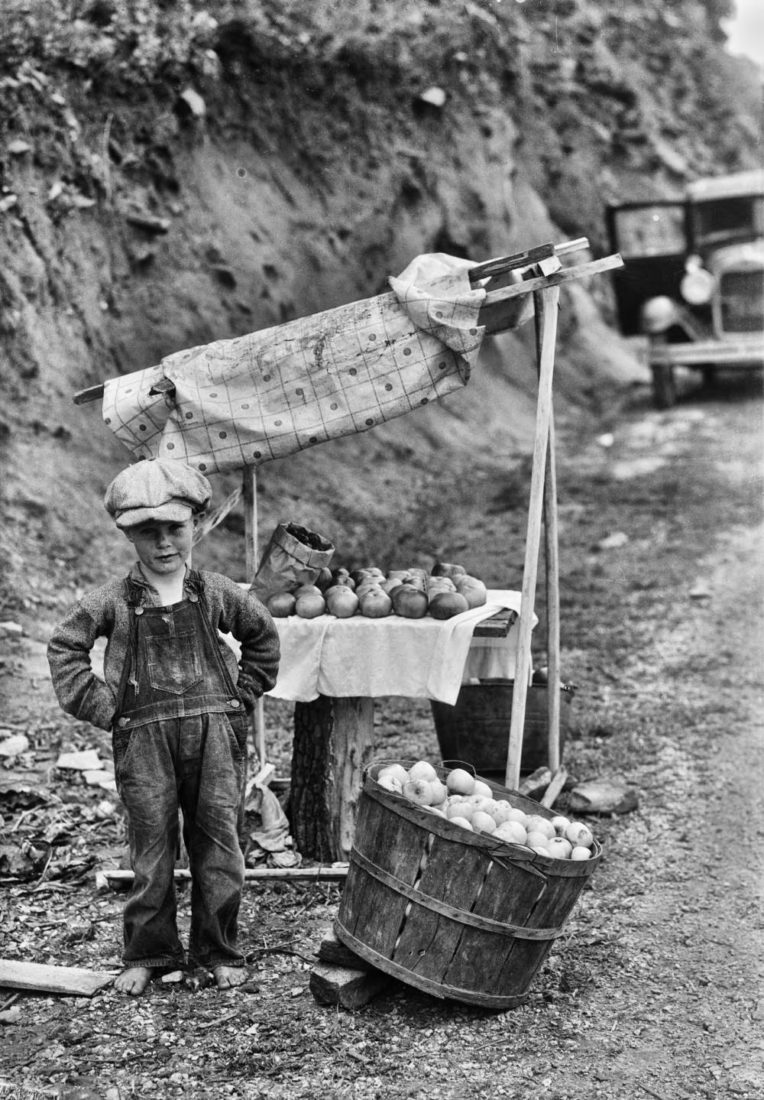

For the next fifty years, Wootten chronicled the gritty realness of American life—women washing clothes, rugmakers weaving, and children selling fruit on dirt roads. “She captured the lives of women that weren’t necessarily deemed worthy to be captured,” says Sarah Tignor, chief operating officer at the Johnson Collection. “Not a lot of people were going to show the daily life of women. It really took another woman artist to do that.” And she did it with an empathetic eye. “She was very good at bringing out the character of the people that she was photographing,” says Stephen Fletcher, the photographic archivist of the North Carolina Collection.

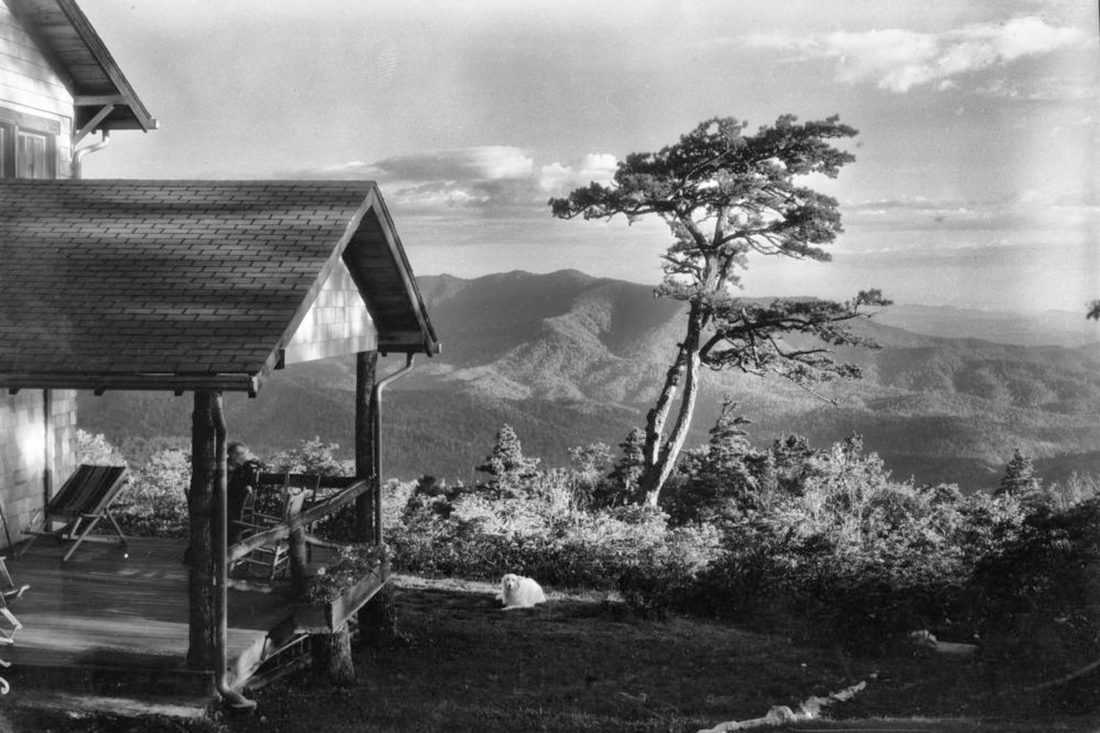

While Wootten primarily made a living taking portraits of people and selling postcards, she also explored photography as a form of artistic expression. She captured scenes of the Carolina coastlines and the mountain people of the Appalachians. “There’s something very special about our region—that glow of humidity,” Tignor says. “I believe Wootten so strongly captured that with her camera by using a soft focus and by stepping away from that really strong black and white, crisp edge photograph that so many people are used to from that time period.”

Wootten was adventurous and an explorer, Cotten says, adding that she preferred exploring backroads rather than working from a studio. “She smoked cigarettes and drank wine and did all the things that a fun-loving person would do,” he says. “I would like to have known her.” During Wootten’s five decades as a photographer, she opened studios in New Bern and Chapel Hill. She photographed soldiers at Camp Glenn for sixteen years as the first woman in the North Carolina National Guard. She flew over New Bern in a Wright Brothers plane and captured photos of the fairgrounds and countryside below, possibly taking the first aerial photograph by a woman. She took thousands of portraits of students as UNC’s official photographer for the Yackety Yack yearbook. And she illustrated six books, including Cabins in the Laurel and Charleston: Azaleas and Old Bricks.

“For a woman to be able to stand up in the early twentieth century and say, ‘I am a working artist,’ was very trailblazing and very gutsy,” Tignor says. “Women had to really elbow in to have a visual voice in art in the American South. And I think Wootten was such a great example of that.”

Wootten died in New Bern in 1959. “At the time, she was probably the state’s most important photographer,” Fletcher says. She was also one of the first to use photography as a fine art.

Cotten was so stirred by the images he discovered that he spent ten years researching Wootten and wrote her biography, Light and Air. He researched her life extensively, talked to her family, and even traveled back to some of the spots Wootten photographed—he’s visited the gravesite of the woman in his favorite Wootten photograph more than once. “I think that if people saw some of her photographs, they would be moved by them, and their interest would be tweaked by them in the same way that my interest was,” Cotten says. “I still look at her work and I’m still marveled by it.”

Today, Wootten’s images can be seen at UNC’s Wilson Library in Chapel Hill.