Arts & Culture

Mississippi Calling

Morgan Freeman has spent a lifetime becoming one of Hollywood’s A-listers, but there’s nowhere he’d rather be than his Mississippi home

Morgan Freeman is both there and not there. He is absolutely present when you are with him—attentive, engaging. And he is certainly present in his acting, in which, exquisitely, he never seems to fill more space than he needs to, but fills that completely.

When he’s not in front of you either physically or on a screen, however, he’s in effect invisible, which is what is required for privacy these days. He doesn’t permeate supermarket tabloids or the infinite iterations of cable entertainment-news shows, and he’s not part of the rotting rubbish heap of celebrity gossip that’s now so ubiquitous we’ve come to think of it as reality. He has had precisely one scandal in just over seventy-four years on the planet, and that little balloon of sensationalism deflated as quickly as it was puffed up, when it was concluded that a car accident with a female passenger, around the time his twenty-four-year-long marriage was ending, was a legitimate accident, and that the woman with him was not a lover.

But Freeman is not shy. He has a powerful sense of self and a charismatic blend of the gentle arrogance that comes from attaining the highest level of confidence and the humility that results from having had one’s ass kicked by life more than a few times. In person his famous deep, annunciatory voice is slightly quieter. He sits erectly at a table, like an athlete, without the seemingly unavoidable stoop of age, and stands straight and ever so slightly imperiously.

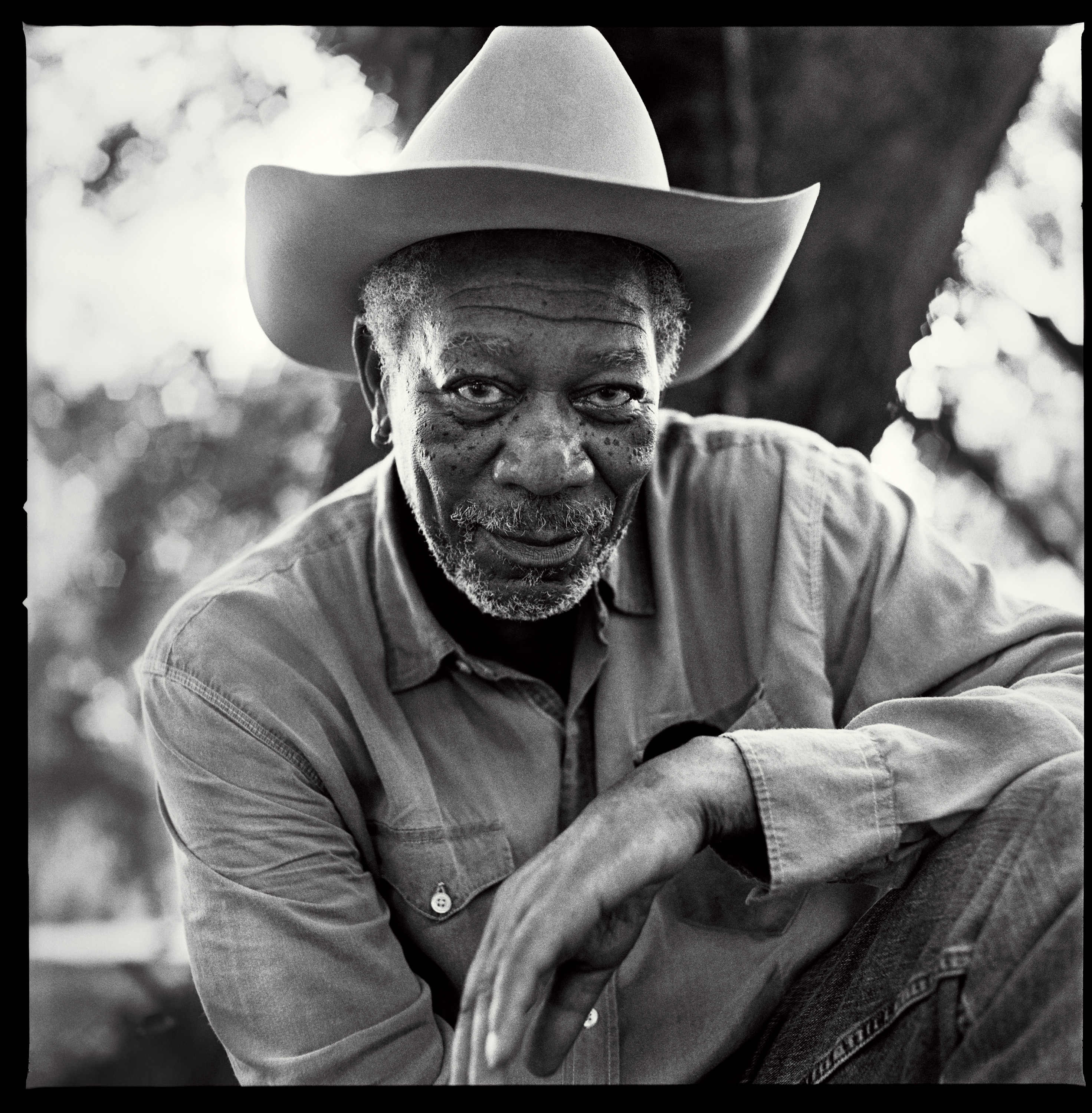

Photo: Jim Herrington

Cowboy Cool

Morgan Freeman takes a knee on his farm near Charleston, Mississippi.

He is so often asked the well-meaning but inescapably patronizing question of how he ever got out of Mississippi that his answer is automatic: “I took the bus!” The more intriguing question is, Why did he come back? “I realized it’s where I was happiest,” Freeman says. “It’s where I belong.” He lives just outside the town of Charleston, on land that his grandparents owned; he bought it from his parents in 1991, and built a beautiful new hacienda-style house on the site. A passionate horseman, he has a number of mounts on the property. Not far away in Clarksdale, he and his closest friend and partner, Bill Luckett, own the world-renowned Ground Zero Blues club and, down the street, an upscale, Michelin star–worthy restaurant, Madidi.

As with Sidney Poitier a generation earlier, it’s hard to imagine that Morgan Freeman hasn’t always been a movie star, film royalty. And as with Poitier, it’s a disservice (or at least inadequate) to call him the best black actor of his generation, when he stands in contention for best actor, period. But he was fifty before he landed his first major movie role, despite two decades of acclaim—not just good reviews but mesmerized critical acclaim—as a stage actor. That film role, as the chillingly menacing pimp Fast Black in Street Smart, earned him an Oscar nomination and propelled him to the front of Hollywood’s mind, where he has remained ever since. This summer Freeman will return as Lucius Fox in the latest Batman movie, The Dark Knight Rises.

Freeman was born in Memphis in 1937, the middle child of five, in the thick mud of segregation, two years before World War II began. When he was six, his family moved to Chicago’s notorious South Side. This was not an improvement. “I hated it,” he once told the New York Times. “There were gangs fighting with knives, ice-picks, and bats. I ran to school and ran home every day.”

School was his salvation. His teachers saw something special in him even then, and some of them, along with his mother, pushed him toward drama. His first role came in a school play when he was eight, and he says he nailed it. “I knew by age thirteen that I was an actor and that’s what I wanted to be.”

At first, that conviction did not last. A few years later, his family moved back south—this time to Greenwood, Mississippi, where he went to high school—and Freeman decided he wanted to become a fighter pilot. “I shifted. I wanted be a warrior. That was just glamorous.” At eighteen, he joined the Air Force and got stationed in Southern California. Eventually he became disillusioned, realizing that the military wasn’t like the movies. The movies were like the movies. So when it came time to re-enlist or get discharged, he left the Air Force and drove the short distance left between him and Los Angeles. “I was in Hollywood,” he recalls. “I’m where I’m supposed to be, but it’s not working out for me, of course. I had some of my hungriest days in Southern California.”

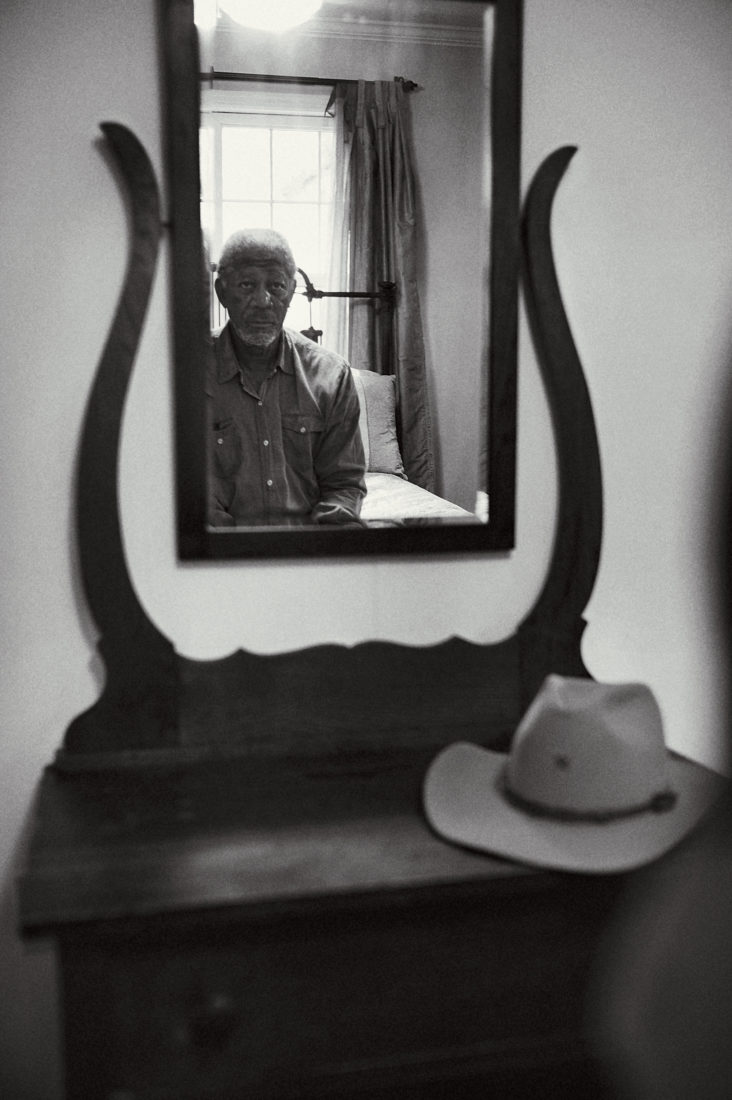

Photo: Jim Herrington

At the Reins

Freeman, with June Bug, keeps a number of horses on the property.

He got a job and a car, and enrolled in acting, voice, and dance classes, but then soon decided to leave. “I had a friend that I’d met who wanted to go to New York,” he explains. “I said, ‘Why don’t we do it? If you want to be an actor, New York is the place to be.’ We drove to New York and I got a good job, but I could not get backstage.” Five months later, he crossed the country again, this time to San Francisco, where he worked at the post office and performed with a small amateur music company until he got fired for refusing, while playing a Native American, to carry the flag. “The lady who ran the company was very nice, but she said, ‘Excuse me?’ And I said, ‘It’s not right. I just can’t do it.’ I read too much history.”

Freeman moved back to New York. It was the mid-sixties now, an exciting time, he says: hanging out with writers and actors, all trying to make it. He performed in off-off-Broadway productions, what he and his friends called “dungeon theater.” He regularly got great reviews. He regularly failed to break through.

In 1971, he landed the role of Easy Rider on the PBS kids’ show The Electric Company, where he remained for six years. It was a good gig, one that many people might have understandably felt was as high as they would ever get. Freeman continued to hone his craft, however, and in 1978 he finally made it to Broadway, as Zeke, an ex–gang member, in The Mighty Gents. After nine performances, the play closed.

When he landed the part of Fast Black, Freeman created the character out of two unrelated bits of cloth. “I was in this bar in Chicago,” he says. “There was this guy sitting across from us, good-looking guy with a Stetson hat, nice jacket and vest, and cowboy boots. He just kept looking at us. He wasn’t flashy. Finally he said, ‘If you need anything, I can help.’ That stuck with me.

“At the time I got the chance to play that role, I lived on West End Avenue at the corner of 92nd Street. A block away, Broadway was a bad neighborhood. Young hookers hung out up there. One night on my way home, I saw one being chastised. The guy never raised his voice. He was talking to her and started punching her. He had her on the pavement. When I auditioned, we were all sitting out there on our chairs. I hear all this yelling and stuff. When it was my turn, I walked in, grabbed the girl by the hair—the scene was the guy threatening to take the girl’s eyes out with a pair of scissors. I laid my fingers on her eyes and I started saying, very quietly, ‘Which one do you want to lose? The left one or the right one? Your choice. Tell me, which one?’ So I got the part.”

Two years later, he got a second Oscar nomination for his role in Driving Miss Daisy, a role he had already immortalized on Broadway. He played God and Nelson Mandela (separately) and a cowboy, putting his equestrian skills to good use alongside Clint Eastwood in the masterpiece Unforgiven. In 2004, he won the Oscar for best supporting actor for his portrayal of Eddie “Scrap-Iron” Dupris in Million Dollar Baby, playing opposite Eastwood again.

When I visit Freeman, it’s a blistering hot day, part of the deep Mississippi summer that starts somewhere in mid-February and seems to wrap up early the following February. I drive down a snaking path napalmed by the sun, park, and enter the cool, today un-air-conditioned house that’s the size of a resort hotel. When I ask how many people live here, he smiles and replies, “Just me!” We sit in his study lined with shelves full of books, while around the room further stacks of books grow like stalagmites.

Photo: Jim Herrington

Famous Face

Freeman in his mother’s former home on the farm.

I ask him, What is the transcendent quality of an actor that makes him believable?

“It’s talent,” he replies. “That’s what the religious call ‘God-given.’ If you have that, all you have following that is an obligation to develop that, use that, share that.”

How does he prepare for his roles?

“It used to be that I would discuss a play or a movie with my wife and come up with an epiphany about a character. But by and large, I don’t do any preparation besides reading the script. When you read a great book, you inhabit all the characters. But if you’re going to play the part of a person like Mandela, then you have to do research. You cannot do that from a distance.”

Freeman met Mandela many times. “I got in bed with him; not literally. Mandela has a very quiet strength. Holding his hand, you just hold his hand. He is not going to grip you. He told me once, twenty-seven years in prison gives you a lot of time to think. He came up with a solution to his life, how he was going to transcend his situation. He would do it with kindness, love, and compassion. He learned from Jesus. Compassion is one of the most powerful tools in human experience. When he left the prison, he was Mr. Mandela to all the guards. That’s power. That is the power of personhood.”

“It’s talent,” he replies. “That’s what the religious call ‘God-given.’

Freeman still gets excited about the next project. When I suggest that it’s obviously not about the money, he laughs out loud and says, “Oh, yes, it is! I don’t kid myself. I’m spread out pretty thin. It’s an amazing thing about money. A lot of people are depending on it. If I stop right now, my Social Security and pension are life-providing, but there are a number of people whose lives would be jerked out from under them. But the real drive is the idea of still doing it.”

When Freeman started out, did he encounter any racism?

“Racism is a strange contemplation when you think about it. It’s easy to say, ‘Yeah, I didn’t do such and such because of my race.’ But to me, that is an easy out. There were not that many roles given to black actors, but then it seemed like the union realized they needed to press for more open casting—if the role doesn’t say black or white, it doesn’t have to be black or white. That happened in the late sixties, early seventies.

“A guy came to me after I moved here and wanted to start a business and borrow some money. I asked him, ‘Can you go to the bank?’ He said, ‘No, they aren’t going to lend any of us any money.’ I said, ‘What “us” are you talking about? Maybe you should go to the bank.’ So, yeah, it’s an easy out.”

And as for the country as a whole?

“I want to see us begin again. Let’s get out of these wars and come on back here. Take all the money we are spending elsewhere, trying to control other places, and start to rebuild the structure. Put money and prestige back into the schools. Start teaching kids in day care. Scientists tell us the earlier kids start to learn, the more capable they are of learning, and we are not taking advantage of that. We start there and we put ourselves back in the running. In ten years we can be on a whole new path in Mississippi.”