Listen to Latria Graham read this column:

“Please make your best effort not to touch the cave formations or any of the rocks around you,” says park guide Rachel Kem to our group of explorers, her hat bobbing as she makes eye contact with each of us. “The oils in our fingers can actually damage the cave features and discolor them. There is one exception to this rule.” She pauses, allowing her words to linger. “If you’re falling—well, grab onto something.” With that she turns and walks with purpose toward the historic entrance of Mammoth Cave.

I nervously pull on my backpack’s straps as Kem finishes the safety briefing. Was I, a fat, claustrophobic, risk-averse writer, really about to descend into the world’s longest known cave system?

“Consider your limitations,” Kem warns before we begin the descent. “Even at such a short distance as we’re going today, medical evacuations can and will take several hours. We are about to go underneath the middle of nowhere in south-central Kentucky.” Even though I am physically capable of making the journey, fear and reason are not friends. “Do it for the story,” I whisper to myself.

In the stories we tell one another about adventure, caves serve many purposes: hideouts, treasure holders, prehistoric homes. They offer welcome respite for fugitives and runaways. Bears, bad people, and monsters make their homes there. Mammoth Cave, Kem explains, most closely resembles a time capsule. The temperature and humidity don’t fluctuate much, slowing decomposition of anything left inside. “Artifacts and signatures from prehistoric times, as well as from the early days of the cave’s rediscovery,” she explains, “are so well preserved that it gives us a good glance into our past.”

About four thousand years ago, Indigenous people frequented the cave in search of minerals, such as mirabilite, gypsum, and epsomite, perhaps for rituals, and those grew there in unusual formations: shapes like tropical flowers, cotton candy, snowballs, even angel-hair strands. Equipped only with bundled cane reeds from the banks of the Green River as torches, they left evidence of their visits—petroglyphs and pictographs, gourd bowls, the mussel shells they used to mine, and sandals woven from a plant called rattlesnake master.

Walking along an ancient streambed, we push deeper. The cave’s length, which with the surrounding land is protected as Mammoth Cave National Park, measures 420 miles, though surveyors often find new passages, so the total keeps growing. The park’s name refers to the size of the cave’s chambers and avenues, not the prehistoric elephant. Back in the time this valley served as the realm of mastodons and giant ground sloths, water created the subterranean network. Moisture funneled into underground streams, which cut through limestone beds as they wound to the Green River.

Fast streams carved out twists and turns like Fat Man’s Misery. Cascades dissolved limestone into tubular corridors like Bottomless Pit. And the steady drip of mineral-infused water rendered endless shapes and designs: calcium carbonite formations, rimstone pools, stalagmites, stalactites, sweeping curves, and golden-hued travertine patterned like folded drapery.

The people who have since plunged into this inky darkness left just as much of an impression, perhaps most so those who found themselves down here without much say in the matter. The earliest laborers in this cave were enslaved people. Before the War of 1812, nearby households rented them out as miners for saltpeter, found in bat guano and one of the three essential ingredients in gunpowder. With whale oil lanterns and lard oil torches, those workers shoveled, hauled, and sifted the cave dirt, enduring long hours and poor conditions. You can still see the centuries-old leaching vats and hollowed-out tulip poplar logs that once aided the filtration process along the trail, those relics all that remain of those men’s lives.

It takes a certain kind of courage to come down here with only a lantern in the hopes of beating back the earth’s impenetrable darkness. In those early days, one wrong step or minor mishap and the cave could quickly become a grave. During our trek, Kem shuts off the guide lights and blows out her candle. We stand for a few minutes, engulfed by black, listening to our organs shift, our heartbeats the loudest things in the chamber.

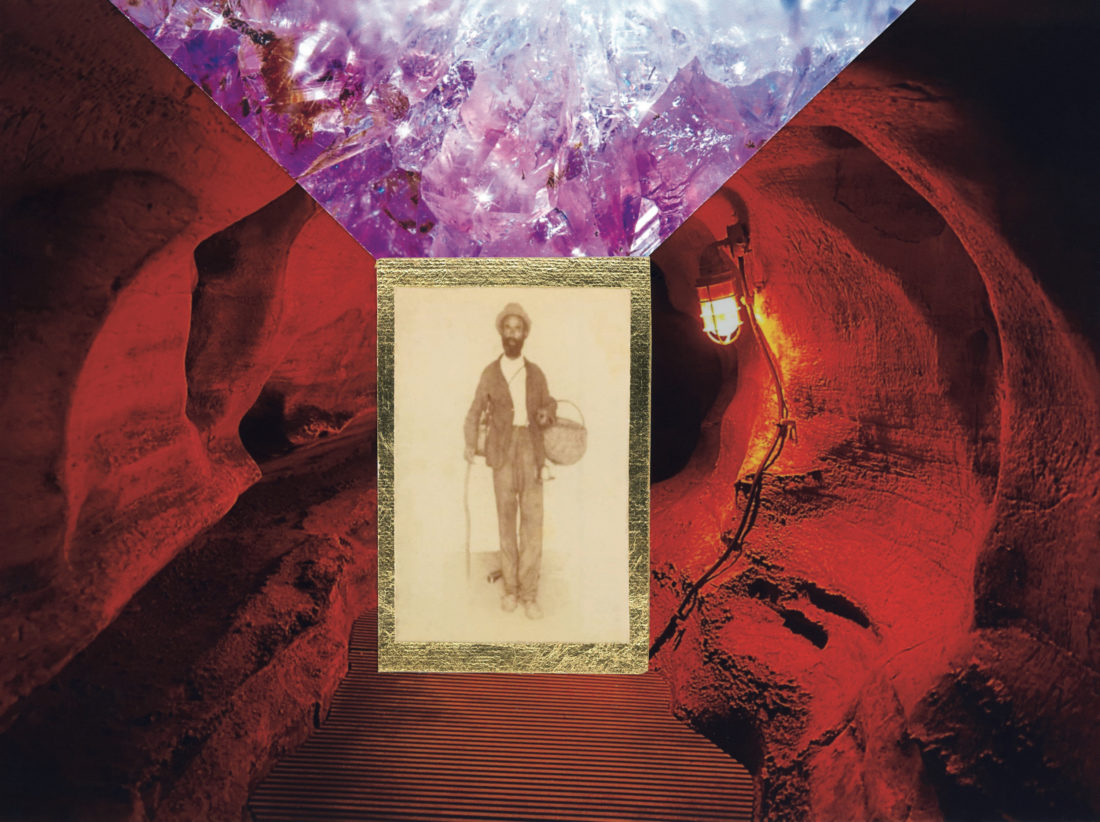

The absence of natural light distorts the passage of time. I think back to the 1830s, when the demand for gunpowder waned between wars and enslaved men worked as guides for wealthy tourists eager to view this underground marvel. Stephen Bishop, one of the earliest documented guides, won praise for his skill and determination, and was the first to cross Bottomless Pit, a 105-foot-deep chasm that, until his feat, hampered surveying of the cave. These guides—folks like Mat and Nick Bransford, Ed Hawkins, Ed Bishop, and a man documented only as “Alfred”—stooped, crawled, climbed, and sometimes slithered, chins in the dirt, down winding passages in the name of exploration. Even if they did not own themselves, no one could take their achievements from them. Letters and journals written by white guests chronicled their feats. When guides would discover a new route, they wrote their names in the rock, along with the year of their accomplishment. In an area now known as the Snowball Room, you’ll find “TO, NICK THE GUIDE 1857 Aug 17th” etched into the wall.

When the men’s owners died, inventories ascribed prices to the enslaved. Stephen Bishop, an estimated $600. Nick Bransford, $800. After manumission, the men and their descendants continued to work as guides, aiding in mapping the cave system. Around the time the area became a national park, segregation was the law of the land. More than a hundred years after their ancestors’ forced arrival at Mammoth Cave, the notion of the Black cave guide would go extinct for a time.

Today, two hundred or so years after the first modern humans entered the cave, thousands of explorers a year brave the harsh, unforgiving terrain here, searching for something beyond what they can see. The testimony of the rock, that enduring witness. The strange beauty of the deep, the menacing shadows the darkness holds. I find myself mapping my own personal topography relative to Mammoth—the at times all-encompassing fear of the things I cannot see, as well as the long trail of history that the park highlights even as our country grapples with it.

The most famous name in that chronology remains here still. Along the park’s Heritage Trail, perched high on the ridge above the cave’s entrance, sits the Old Guide’s Cemetery. In it, a headstone reads: “Stephen Bishop, First Guide & Explorer of the Mammoth Cave. Died June 15, 1859. In His 37 Year.” His grave, with its date of death off by two years, has a perfect view of the sunset.

In the precious hours of early morning, I make my way back to that same ridge to watch the Geminid, the spectacular annual meteor shower. As I sit on a bench and sip tea from my thermos, the faraway dust and rocks leave a luminous trail that lasts mere moments. We are here for only a few seconds, I think. But in the hours before dawn, I feel like a conduit, tethering the heavens above, the depths below—what luck, to be cognizant in an age when I can spot constellations in the sky and identify formations underground, both millions of years in the making, the timescale of their creation far exceeding anything we have endured and will ever comprehend. I ponder again the human life in the cave over the centuries, the thoughts of my predecessors, their ties to the sublime. What stories did they tell about peering over the cusp of the known world, of staring directly into the void?

Stephen Bishop, Mat and Nick Bransford, and other Black guides who worked in the cave system might have come the closest that an enslaved person could to immortality. At a time when it was rare for Black people to be allowed to write their names, they were able to leave their mark: to proclaim their existence.