When Sam Jones opened a two-million-dollar barbecue restaurant in November, he chose a spot on a suburban thruway on the edge of Greenville, North Carolina, less than ten miles from Skylight Inn, the joint his grandfather Pete Jones opened in 1947. The Skylight roof is shaped like the U.S. Capitol rotunda. Showing a flair for spectacle that his son inherited, Bruce Jones, Sam’s father, erected the neoclassical dome in 1984 after the National Geographic Society called Skylight the capital of barbecue. Asked why, Bruce Jones would say with a sly grin that he was “capitol-izing” on the family reputation.

Sam Jones BBQ is its own spectacle. The dark-timbered exterior recalls a pole barn rethought by Disney or a ski lodge designed by Billy Reid. Two piebald pig chandeliers, impaled with filament bulbs, hang from trussed beams. When customers queue to order at the counter, they face placards that read LEAVE IT TO CLEAVER and A MAN AMONG PIGS. But these are mere diversions. The restaurant best showcases the wearying labor of barbecue: Along the far wall, fixed on smoke-charred barrelheads, Jones family men stare back from sepia photographs. Standing awkwardly before the camera with, say, a shovel in hand, they look agitated, as if stopping for a picture when there’s work to be done was an insult they tasted in the backs of their throats.

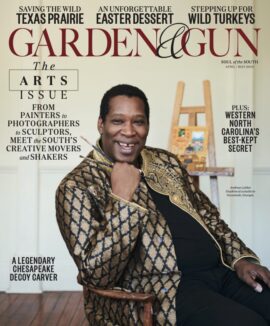

Photo: Lissa Gotwals

Sam Jones at the doorway to his new pit house.

The key architectural element stands outside: a pit house, ventilated by screened windows, topped by a tin roof, with a Janus-faced fireplace at the center and a pit array along the flanks. The smoke that trails from the brick chimney inscribed with Sam Jones’s initials is the true signature. Day and night plumes lift skyward, as soot-streaked pitmen wheel into the building with gutted pigs as pale as peaches, and wheel out sixteen-plus hours later bearing crisp-skinned beasts gone cordovan in the hickory smoke.

Skylight now serves the Jones family as a homeplace. In the same manner the original Shake Shack in Madison Square Park in New York City grounds the international group of restaurants that Danny Meyer operates or the first Waffle House in the Atlanta suburb of Avondale Estates reminds patrons of how they grew up on those padded stools, Skylight is where pilgrims reconnect with the roots of the tradition. It serves as a place for reflection, a shrine to family and permanence.

At the ribbon cutting for the new restaurant, the local chamber of commerce executive director said a few words. So did a county commissioner. Fire department officers, wearing regal uniforms with spangled epaulets, stood at attention, their chests puffed with pride. As the speaker system blasted “East Bound and Down,” from the Smokey and the Bandit sound track, Jones cut a red ribbon with oversize gold and silver shears and thanked his family, friends, coworkers, and God.

Photo: Lissa Gotwals

Pork spareribs.

A college town, pulsing with new arrivals, Greenville has long been a great place to try out new restaurant ideas. Fifty-plus years before, in that same coastal plain town, Wilber Hardee opened the first location in what would become his burger chain. A generation later, Hardee’s reinvented the biscuit breakfast, transforming it into a drive-through mainstay. Jones won’t reinvent barbecue with this new restaurant. That’s not his aim. But he might revitalize the business of barbecue. He may show a new generation of pit masters that barbecue can be a remunerative vocation that sustains a family for generations.

When Jones opened, detractors crawled out of the woodpile. Some took issue with his choice to pour beer, while most barbecue places in this part of the state serve nothing stronger than sweet tea. (The Cack-a-lacky ginger pale ale from Fullsteam plays well off the pork spareribs, a new dish to the Jones family canon, developed by Jones and his business partner, Michael Letchworth.) Others complained about the prices. (In a town where sandwiches made with gas-cooked pork can be had for three bucks and change, Jones’s overstuffed sandwiches of wood-smoked pork run six bucks and change.) But few complained about the barbecue, cooked over glowing oak until it tastes like a benediction to the possibilities of pig cookery.

Photo: Lissa Gotwals

a cleaver on the block.

Jones feels the pressure. “He’s got a capitol on his shoulders,” whispered a friend there for the ribbon cutting. Now juggling two locations, he is going to great lengths to prove he can bear that burden. At Skylight, customers expect the menu to be short and the service to be curt. But when you open a barbecue restaurant with a cathedral ceiling and a marble-topped bar, customers want more. They want mac and cheese that’s both gooey and crusty. They want salads, tossed with whole hog and cornbread croutons. They want BevNaps. They want big smiles and sincere welcomes. In a training conversation with a waiter, Jones put it this way: “Don’t go walking up to a table with your head hanging down like somebody just ran over your puppy.”

If Jones convinces customers that he can straddle what Skylight is and what his new restaurant can be, he’ll succeed. To weave that tether, employees at Sam Jones wear hats blazoned with the Skylight Inn logo. And when customers walk in the door, they hear the same staccato whack of cleavers hitting the cutting board, chopping crackly skin and ruddy meat into a smoky hash.

“That a change is now in course all over the South is plain; and it is as plain that the South changing must be the South still,” Stark Young wrote in I’ll Take My Stand, a 1930 agrarian manifesto. Each time Jones steps into the smoke, he faces down that dichotomy. Sam Jones BBQ doesn’t look like his father’s restaurant. But the pork that emerges from his brand-new pit house is honest barbecue still.