Winston Groom recalls being pretty satisfied with his 1986 novel, Forrest Gump. It was reviewed favorably by many literary critics and sold around 30,000 copies in hardcover.

By then, Groom was in his early forties and in the midst of creating a nice, steady writing career. After graduating from the University of Alabama, he had done a stint in the army and a tour in Vietnam. He’d worked in Washington, D.C., as a reporter for the Washington Star, covering the court system, and then quit that job to start writing books. He moved to New York City, where he haunted the literary scene, pal-ling around with the likes of Kurt Vonnegut, George Plimpton, and Joseph Heller. He’d written three well-received novels (Better Times Than These, As Summers Die, and Only) and a nonfiction book about a POW in Vietnam that became a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. Forrest Gump, his funny-but-touching novel centered on a simpleminded man from Alabama, was another positive step in a budding literary career.

Then came July 6, 1994, when the film version of Forrest Gump—directed by Robert Zemeckis and starring Tom Hanks, Robin Wright, and Gary Sinise—was released nationwide. It became an immediate hit, both culturally and commercially, winning six Academy Awards (including Best Picture) and pulling in $678 million at the box office worldwide. The rising tide of the movie lifted Groom’s book to the top of the best-seller lists, and it eventually sold close to two million copies and spawned two best-selling spin-offs, Gumpisms: The Wit and Wisdom of Forrest Gump and Gump & Co.

The movie changed his life (“I upgraded to a better brand of toilet paper,” he says), but Groom has continued to churn out high-quality books, mostly about history and American wars (he’s currently at work on book number twenty-three), writing in an office in his house in Point Clear, Alabama. Though he has long since moved on from Gump, Groom says that rarely a week goes by without someone reminding him about it. On the twenty-fifth anniversary of the movie’s release, Groom, now seventy-six, reflects on the Gump phenomenon.

Photo: Jacqueline Stofsick

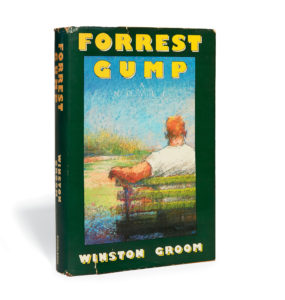

A first edition.

How did you come up with the idea for the book?

I was living in Manhattan at the time, and I also had a house in the Hamptons. Both of those places were awful in the wintertime, so I went home to see my dad. He was a lawyer, born in 1906, living in Mobile. My mother had passed away. We had lunch in a restaurant downtown, and he started reminiscing about his childhood. In his neighborhood, there was a boy who was what you would call slow-witted, and the kids in the neighborhood would tease him and chase him and throw sticks at him. Then one day this truck arrived outside of the boy’s house, and out of it came this big piano. And within a few days, this beautiful piano music began wafting out of the windows. It turned out that this boy was some sort of musical genius. The kids stopped picking on him then and took him under their wings. 60 Minutes had also recently run a story on what was called the savant syndrome, where a person could barely tie his own shoes but could perform remarkable math or memory problems. I went home and started to make notes on that conversation, thinking I might use it as a scene somewhere in a book. By late that evening, I had written the first chapter of Forrest Gump.

That name is so much a part of the character.

When I came back from Vietnam, the plane landed in San Francisco. I wanted to meet some girls, and I learned very quickly that in 1967 in San Francisco, if you wanted to meet girls, you didn’t do it in the uniform of a lieutenant of the U.S. Army. So I went downtown to look for some civilian clothes. I wound up at a department store called Gump’s. That name must have stuck with me. There is no real Forrest Gump character that I know of, even though my friend Jimbo Meador gets accused of it all the time.

Jimbo played a role in the film, right?

He did. Tom Hanks’s voice coach wanted to get down what she called the “Point Clear accent.” She called me, but I said I wasn’t the right person. I sent her to Jimbo, and she recorded him and used that to coach Hanks. There’s a funny story about Jimbo and the movie. Want to hear it?

Yes!

I was in New York just after the movie came out, and Jimbo called me and said he’d gotten a call from London’s Sunday Times, and they wanted to do a story on him and he wanted to know if that was okay. I said sure, but I warned him to not let them talk him into any trick photos or anything like that. He did the interview. His wife was in the supermarket checkout the next week and she sees News of the World, which, like the Sunday Times, was owned by Rupert Murdoch. I guess they share stories. Anyway, there on the cover was Jimbo, sitting on a damn park bench under the title “The Real Forrest Gump.”

Photo: © Paramount Pictures Corp. All Rights Reserved

Filming locations included Bluff Plantation in Yemassee, South Carolina.

I read somewhere you wrote the book in six weeks.

I did. I remember Joe Heller once telling me that Catch-22 wrote itself. I’m not sure I believed him, because that was a very complex book. But Forrest Gump really did. It’s something that had never happened to me before and hasn’t happened since. I’d sit down in the morning and say, “What’s he going to do today?” And I think the thoughts flowed from what I call the lizard brain, which is down in the back of my neck, and straight onto my ten fingers at the keys. Very early on, I had him playing football for Bear Bryant at Alabama. I thought if readers would believe that a perfect idiot could play football for Bear Bryant, they’d believe anything. Once you get the reader to suspend disbelief, you can do what you want.

How did you feel about the book when you finished it?

I thought people would either think I was crazy or they’d love it. I sent it to my agent and waited a day or two. The phone rang, and all I heard was the sound of laughter. My agent said, “I love it.” He sold it pretty quickly. One great thing about the book is that it got me home. For some reason, it made me want to leave New York and come back and hang out with my friends in Alabama.

The book was picked up quickly by a movie studio, right?

In galleys, if I remember correctly. A woman named Wendy Finerman found it. She worked for Steve Tisch [a movie producer], and she was married to a head of Warner Bros. at the time. Warner and Tisch worked out some deal. They asked me to come out and work on the screenplay. (I remember when I went to Warner, there was the original screenplay for The Maltese Falcon sitting on the table, probably there to impress people.) I took a shot at a few screenplays for them. I had lunch with the Fonz, Henry Winkler, who wanted to do the movie, and put in some of his ideas. But after a few iterations, it was clear something wasn’t working. One of the problems was that the Forrest in my book was too big. He was six foot six and 240 pounds, and John Wayne had been dead for a while and Schwarzenegger didn’t have the right accent. I couldn’t get it exactly as they liked, so they fired me. I learned later that this happens all the time. I was okay with it. It’s hard to have your heart in it when you’re tearing your own stuff up.

And they did end up changing some things. In the book, Forrest is a pro wrestler, a chess grand master, and an astronaut.

I wanted them to keep in the astronaut stuff. Forrest goes up in a spaceflight, and he comes back and meets Raquel Welch, and they cavort nude around Hollywood. I was wondering who was going to play Raquel Welch. Parts of the book were farce. Hollywood doesn’t do farce that well. The French do it better. They wanted something more serious.

It took eight years for the movie project to get going. How did it finally happen?

I was at Elaine’s one night with Pete Hamill and a lot of regulars. One guy turns to me and says, “They’re making the movie about your book at Paramount.” I told him, “That’s news to me.” The guy told me Paramount had gotten it from Warner Bros. I couldn’t believe it. I found out Eric Roth had done the screenplay and Bob Zemeckis was directing and Tom Hanks was starring. I had not seen Hanks in anything other than Bosom Buddies. So I went to see Philadelphia, and I realized he was a really fine actor. Everything went fast from that point on.

Did you ever visit the set? A lot of the movie was shot in the South, from Forrest’s park bench in Savannah to

the Vietnam scenes on Fripp Island, South Carolina.

I didn’t. I’d visited the set for a movie made from another one of my books, As Summers Die, which was one of Bette Davis’s last films. It was boring, and I think having the writer around makes people nervous. I cringed a bit when I saw the Vietnam scenes in Gump. The trees in it were cabbage palms like you see in shopping centers in Florida. In Vietnam, they don’t have cabbage palms. I bet I’m one of the few people who noticed. I did catch a few things for them in the script before the movie came out. They had Bubba playing football for Alabama in 1966, but that was before the Bear had integrated the team. They said, “No one will notice.” I said, “Oh yes they will.” They changed that.

Photo: © Paramount Pictures Corp. All Rights Reserved

Fripp Island in the South Carolina Lowcountry provided the backdrop for Gump’s Vietnam scenes.

When did you get an inkling the movie might be a huge deal?

I was in Savannah and I was watching the Today show, and they had an enormous ad for it and I thought, Good God Almighty. I realized they were spending a lot of money backing it.

And then?

Boom. It opened. I didn’t go to the premiere in Hollywood. But Paramount gave me my own screening at the Carmike Theater in Mobile. I invited a couple hundred of my best friends. They had a tent outside with a bar and food. And then we went in to watch the movie. It’s funny watching your own stuff, to hear your words roll off the tongues of actors. But after about ten minutes, I just got into it. They did a great job. I sat there stunned when it was over. Everyone sat very quietly and then stood up and cheered, and the mayor presented me with a one-sheet, the advertisement poster, sent by Paramount, that all the actors signed. I have it hanging in my office.

Things got a little strange after that, right? Everyone was trying to figure out who Forrest Gump was, and what he meant.

It drove me crazy. People on cable news were arguing if Forrest was a liberal or a conservative. Journalists were calling to ask my opinion. I told them I had no idea, and I don’t think Forrest did, either. It started to get ridiculous. Someone wrote a piece for the Washington Post and said Forrest had no ambition and was a terrible role model. About that time, I headed for the mountains to escape it all and didn’t answer the phone for a couple of months.

Did you go to the Oscars?

I did. The night before, there was a big party. I was talking to Hanks and he said, “I’m not sure you did me any favors here. They’re going to want me to play this character forever.” I told him I was in the same boat. The next book I wrote could be the Bible and all people would want to talk about is Gump. The ceremony was fun. I sat next to Bubba’s mom. There was some controversy that no one mentioned me in their acceptance speeches. Pete Hamill and a bunch of people were watching at Elaine’s, and they were pissed. He called me the next day, and I told him I didn’t care. This was not the Pulitzer Prize. It was the movie people’s time to shine.

When you look back at it all now, what comes to mind?

It’s been a helluva ride. There’s not a week that goes by that half a dozen people don’t ask me for an autograph for Gump. I’ve been thinking about it a bit more recently because work has started on a musical adaptation. In the end, I’m just really damn grateful for the whole thing.