The Sporting Life

The Other Montana

While they may not get the attention of the storied waters out West, two East Tennessee rivers—the South Holston and the Watauga—hold the kind of brown and rainbow trout that usually only swim through anglers’ dreams. Welcome to the Tennessee Tailwaters

Photo: Forest woodward

Guide and boatbuilder Matt Maness works a section of the lower Watauga River.

He goes by “Scooter” because that’s how he got to the river. After the DUI, the jail time, the realization, he tells me, that the path he was walking would lead to either a life in prison or the grave, he moved back home to Bristol, Tennessee, to live with his mother and father. He was twenty-five, broke and broken and fresh out of pride, so he bought a used yellow motor scooter, stuck a Patagonia sticker on the gas tank, and rode to the river wearing chest waders with a fly rod stuck between his legs. He did this most days. For three years.

Photo: Forest woodward

“Scooter” Guinn.

He tells me this as he changes the fly I’ve been casting to South Holston River trout, in the corrugated Southern Appalachian ridgelines of East Tennessee. Scooter—his given name is Matthew Guinn—is a bear of a man, six foot five, with scraggly facial hair that hasn’t quite figured out if it’s a beard or a goatee. He’d seen a nice brown trout nose up to my fly, then reject it outright. “Umph,” he grunted. “I don’t like how he turned away.” He snips off the Puff Daddy dry fly—a slim silhouette tied to imitate a sulphur mayfly—and swaps it for a crippled emerger, a fly designed to look like a small mayfly struggling to crawl out of its larval shell. “The fish see that crippled fly and they’re not so worried about the bug getting away,” he explains. “It gives the fish a bit of confidence. Might be all they need.”

This is where entomology meets East Tennessee horse sense, and the payoff is immediate. On the next cast, the trout takes the fly and turns downstream. A good fish, maybe eighteen inches, and it uses the river flow to fight each inch of the way to the boat. In the next thirty minutes, I land a half dozen fish on that crippled emerger fly. Scooter sits at the oars, beefy arms crossed, and smiles. There is sunlight on the riverside sycamores and towhees calling from the woods. At times a dozen fish rise within range. Scooter says little, trying not to break the spell. This river and these fish, I have learned, saved his life.

Photo: Forest woodward

The Watauga and the South Holston hold impressive numbers of large rainbow and brown trout.

The redemptive power of east Tennessee’s trout waters is no surprise to a growing number of anglers. Two big rivers, the South Holston and the Watauga, drain some of the most historic mountain ground in the South. Daniel Boone explored this country. Early settlers leased land from the Cherokee through the Watauga Association, a semiautonomous government that sowed the seeds for the state of Tennessee. The rivers draw their waters from some of the region’s highest peaks—the Watauga is born on the high ridges of North Carolina’s Grandfather Mountain—but as they push through the Tennessee valleys, they slow and braid into wide, shimmering riffles and ledge pools.

Both of these streams is a tailwater river, meaning that they are dammed for hydropower generation. Since the released water comes from the bottom of the lakes, it stays consistently cold even through summer heat, and so trout thrive in these rivers, in astonishing numbers. The South Holston River holds an average of 8,500 trout per mile, and four out of five are wild brown trout. The Watauga, a smaller stream that careens under limestone cliffs, holds nearly as many. Fish in either river can grow to legendary size. Twenty-inch fish aren’t uncommon. Thirty-inch fish aren’t unknown. In the middle of six-inch native brook trout country, the big fish and rowed drift boats give East Tennessee a decidedly Western inflection. They have created a microcosm of serious big-fish trout-fishing culture unlike anywhere else in the region.

Photo: Forest woodward

Working the drift.

There are few lodges by the water, and a handful of campgrounds and cabins to rent. So it’s mostly a day venture, and every weekend, dozens of guides descend on the rivers. They migrate from the North Carolina mountain towns of Boone, Blowing Rock, and Asheville. On the Tennessee side, caravans converge from Knoxville and Elizabethton. Trucks pull trailers loaded with drift boats, the cabs stuffed shoulder to shoulder with anglers, fishing packs, and gas station coffee cups. It’s part Carhartt, part Simms. Fried bologna sandwiches and nine-hundred-dollar fly rods.

“Of all the places I’ve fished,” says David Grossman, who runs the online journal Southern Culture on the Fly, “it’s the weirdest, coolest little corner I’ve happened upon.”

But this is no Twin Bridges. At many famed trout-fishing destinations out West, fly fishing defines a regional aesthetic, remaking small towns into catalogue-perfect fantasylands where you can buy fifteen-dollar cocktails named after trout flies. Not so much in East Tennessee. There’s no village atmosphere that’s grown up around these rivers, no local pubs where all the guides hang out, no gentrified downtowns stuffed with overpriced art galleries. The nearest city is Bristol. It sports a growing hip vibe, for sure, with craft breweries and a raging bluegrass scene, but there’s an old-time/new-school mash-up feel to the town. My favorite find is a rocking all-night sweet shop, the Blackbird Bakery, which cranks out two thousand doughnuts a day in a two-story art deco space where the line often runs out the door. Still, Bristol is better known for its NASCAR roots than as a tony fly-angling enclave.

Photo: Forest Woodward

From left: Suds at Studio Brew; Matt Maness and pup; State Street.

East Tennessee’s fishing culture, in fact, seems to be atomized throughout the surrounding counties, and you can’t really tell by outside appearances which country store or crossroads diner might be a gathering place for anglers. One day after fishing I wander into Webb’s Store, outside Bluff City, where the South Holston River spills into the eponymous lake. Mark Price has run the place for seventeen years, and while a store has been on this site for more than a century, Webb’s is more restaurant than commissary. Price makes buttermilk biscuits from scratch six days a week. Soup beans and cornbread and collard greens, and tomatoes from his garden back home. Folks stand in line for his fried chicken. “People tell me, ‘Mark, your gravy tastes just like Granny’s,’” he says, laughing. “And that’s because it’s my granny’s recipe. People can’t believe a place like this still exists.”

Webb’s Store might be off the beaten path—it has but a single Yelp review, although that one is a five-star write-up—but it’s one of those places that you’d never miss returning to once you found it. The famed fly angler Lefty Kreh always stopped by to take country ham biscuits home to Maryland. Flip Pallot eats there when he fishes East Tennessee. “I’ll look up and fishermen will be standing outside the door in their chest waders, peering in the windows,” Price says. “I’ll just holler out, Why, Lord, yes, come on in! That’s the whole reason why we have a concrete floor.”

If the East Tennessee tailwaters region does have a center of gravity, a place where its soul is most keenly felt, it’s a squat two-story building set in a curve where a two-lane country road in Sullivan County falls away through pasture. With walls of bricks baked from river mud, the South Holston River Fly Shop was originally a restaurant that the Tennessee Valley Authority opened in the 1940s for its workers building the South Holston Dam. A father-and-son pair, Rod and Matt Champion, converted the abandoned diner into a fly shop in 2006, and it’s widely credited with bringing the river to the attention of the national fly-fishing scene.

Photo: Forest woodward

The greeter at the South Holston River Fly Shop.

And with providing a local hub of employment and downright pride. “Ninety percent of our guides are family people,” Matt Champion explains. “They’ve got kids at home. They’re not here for summer break, to make a buck and be gone. They’re not here to get a few years of experience and take off to Montana. That’s not what we’re after.”

Scooter Guinn calls Rod Champion “the chance giver” for his commitment to the community and for giving opportunity to a few diamonds in the rough. “Oh, I’ve had some projects,” Rod says, laughing, when I call him to ask for his version of the story. “But this is a very poor area, and we’ve provided a pretty good income to a lot of people. I’ve seen a few lives turned around right here. There’s a lot of satisfaction in that.”

Photo: Forest Woodward

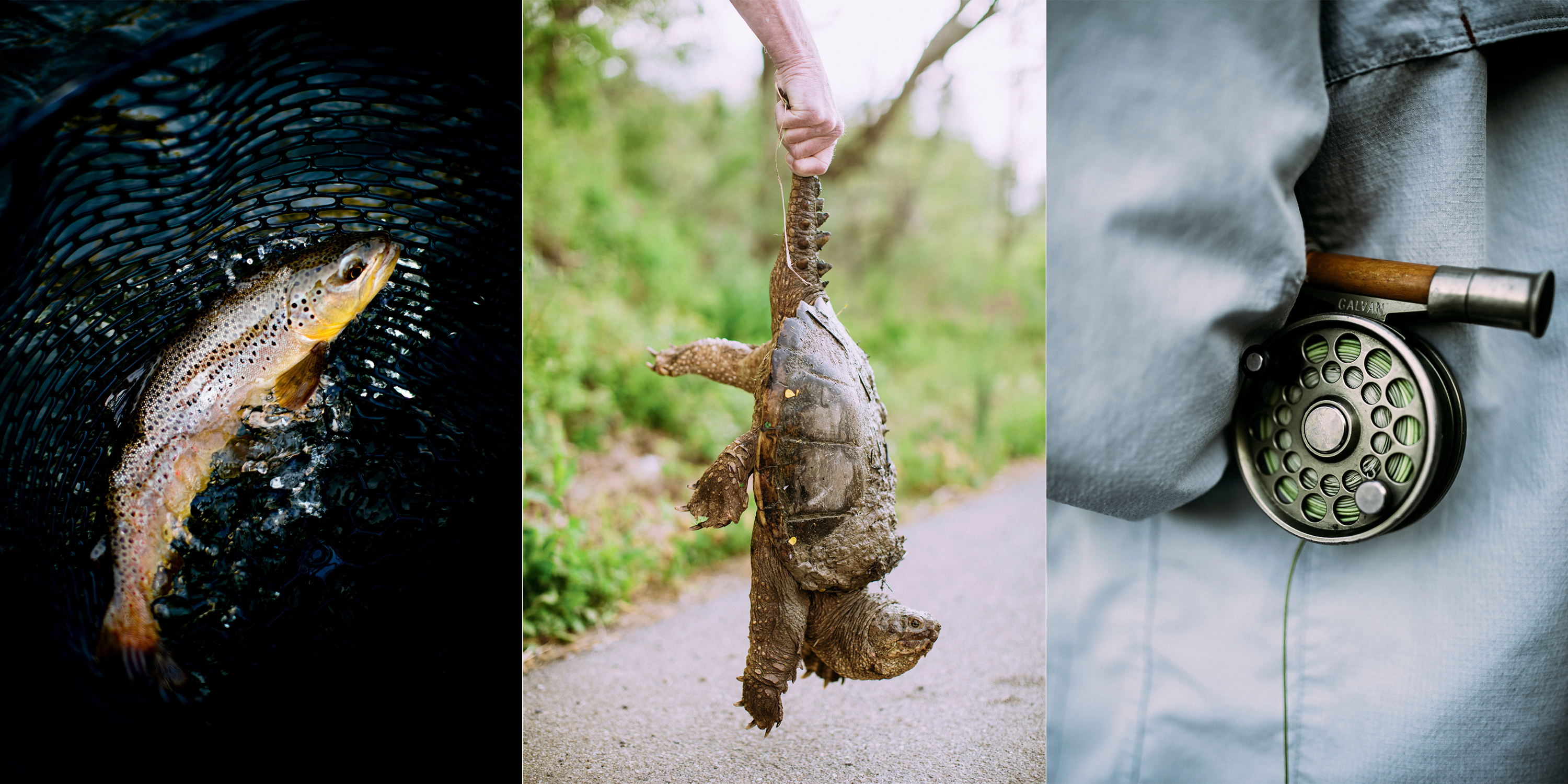

From left: A brown trout prior to release; a turtle gets a lift; tool of the trade.

That sense of authenticity, and connectivity, is obvious as soon as I walk through the doors. Cole, an eleven-year-old German shorthaired pointer, thumps his tail twice in greeting. Drift boat oars are stacked in one corner, near racks of sulphur dry flies for which the South Holston is famous. On a chalkboard where guides keep a running daily tab on which insects are hatching, there’s the admonition Mamas, don’t let your babies grow up to use spin rods. Shop manager Robert King is behind the counter, ponytailed and bearded, chatting with the sales rep for Hardy fly reels of England.

Photo: Forest woodward

The South Holston fly shop.

King grew up in Mississippi, he tells me, then spent twenty years in Montana and Colorado as a fishing and hunting guide. “I was one of those Eastern kids that get hooked on fishing and all they want to do is head West,” he says. “When I turned forty, I told myself I was going home to live in Sperry’s and khakis and never shovel snow again. I researched the best dry-fly fishing in the South, and here I am.”

Despite the high-end gear, there’s still a pleasing whiff of hardscrabble here. It’s not a place that puts on airs. “People of all shapes and sizes come into this shop,” King says. “They’ll walk in with bare feet and overalls and ask for grizzly hackle so they can tie tiny midges for winter fishing. I’ve had days when there are folks in here dropping nine hundred dollars on a fly rod and then some kid walks in with a dead trout in a Walmart sack to tell me that fly I sold him done real good. True story. It’s a subtle little scene up here, but that kind of stuff happens all the time.”

Photo: Forest woodward

The South Holston.

One of the appealing features of these east Tennessee tailwaters is their year-round fishability: You can float the South Holston and the Watauga spring, summer, fall, and black-iced snowy winter. Still, a few periods stir up particular anticipation. In late summer through early fall, afternoon hatches of sulphur mayflies bring trout to the surface for perhaps the finest dry-fly fishing east of the Mississippi. And during a roughly three-week stretch in April, a dime-sized insect called the black caddis fly hatches in mind-boggling numbers.

Trout lose their marbles when the sulphur and caddis fly hatches are on, and anglers go a little nuts, too. On a late April morning my son, Jack, and I push into the Watauga’s middle section with Matt Maness, a guide who operates out of Foscoe Fishing Company in North Carolina. It is early enough in the day to call for fleece jackets with our river sandals, and the cool air has me scanning the water’s surface for a hatch. There isn’t a bug to be seen, but Maness is unfazed. He points to the hull of the boat, smeared bow to stern with caddis flies from the previous day’s fishing. “It’s typically an afternoon thing,” he says, and grins. “Let’s hope we have a repeat of yesterday.”

Photo: Forest woodward

Maness at home.

The Watauga River sports more drop than the South Holston, with the big woods of the Cherokee National Forest crowding the river under soaring limestone bluffs. We land browns and rainbows, often trading casts so we can watch each one eat and fight. Then Jack hooks a significant fish in the deep water, and fights a wild nineteen-inch Watauga brown trout that rips line from the reel. Maness drops anchor, scoops the fish into a long-handled net, and brings it to the water’s surface. Splattered with coffee-brown spots and blood-red splotches, it has a kype jaw held over from the spawning season, the mark of an old fish.

Catching and landing just such a big, wild trout from a drift boat is the signature experience of Tennessee’s tailwaters, and fishing with Maness brings an added dimension to the game: He built the very drift boat from which we are fishing. During the winter months, Maness and another North Carolina–born friend and business partner, Colorado guide Les Vance, craft a half dozen or so fiberglass drift boats they’ve designed specifically for whitewater rivers like those of the Southern Appalachians.

Soon the late April afternoon caddis-fly hatch grows so thick that Jack and I have to pull sun buffs over our mouths and noses to keep from sucking insects into our lungs. At the head of a wooded island, limestone ledges stitch across the river bank to bank, and the flow quickens as the water streams over countless pockets carved from the soft rock. For a hundred yards, dark slashes of deep water lie to the left and right, each one perfect for harboring big fish.

Photo: Forest woodward

Maness on the hunt.

Maness back-rows hard, slowing the boat so it rides the slow seam of a long eddy line that spools off the ledges. Black caddis flies boil over the water, where trout dimple the surface for as far as I can see. I wedge my thighs into the drift boat’s leaning post and cast a soft-hackle fly toward the current seam, mentally calculating the odds of a fish singling out my offering in such a groaning board of winged food. The fly bobs in the frothing current, then disappears, and for a split second I think heavy water has drowned the fly until I see the line streaming cross-current. When I set the hook, the rod bends all the way to the handle.

“Oh, boy,” Maness murmurs. “That’s a fish.”

I scramble to clear the line from underfoot as the trout screams across the river, unstoppable, zipping line from the reel. When the fish turns downstream, the reel zing rises an octave. “Hang on,” Maness says. “We gotta chase him.”

In three oar strokes he puts the boat in the main river current, and the rush of water carries us arrowing downstream. I reel furiously, rod high overhead to gather line, as Maness closes the distance. He drops the boat in a pool behind a hump of limestone that breaches the surface, and I settle into an honest fight. The fish turns, and I lead it to within twenty feet of the boat, as we strain to catch our first glimpse of such a strong fish and all feel the rush that comes when the contest turns in your favor. And that’s when the line parts. The rod snaps backward and the utter weightlessness in my hands feels like the heaviest burden of all.

Photo: Forest woodward

A rainbow.

I slump in the bow of the drift boat, stunned.

After a few seconds, Maness offers up all the encouragement he can muster. “Oh, man,” he says. “Oh, man.”

He is quiet for a moment, letting the river carry the disappointment downstream like a dead branch. Then he pushes the boat into the current, and I hear the oars work.

“On the right,” he says. “You see that dark water?”

I’m in casting range in just a few seconds. The choice is mine: Pout or fish. Maness deftly angles the bow to the right, for a straight-on cast, and I square my shoulders to the Watauga River current and let fly. I’ve been on these Tennessee tailwaters enough times to be confident of one thing, at least: Every pool can hold a fish big enough to salve a wounded spirit. Every cast can bring redemption.

Photo: Forest woodward

Catching the drift during an early morning on the Watauga.

1 of 5

Photo: Forest woodward

A High Country drift boat.

2 of 5

Photo: Forest woodward

Tying flies.

3 of 5

Photo: Forest woodward

Matt Champion.

4 of 5

Photo: Forest woodward

The Paramount in Bristol.

5 of 5