Arts & Culture

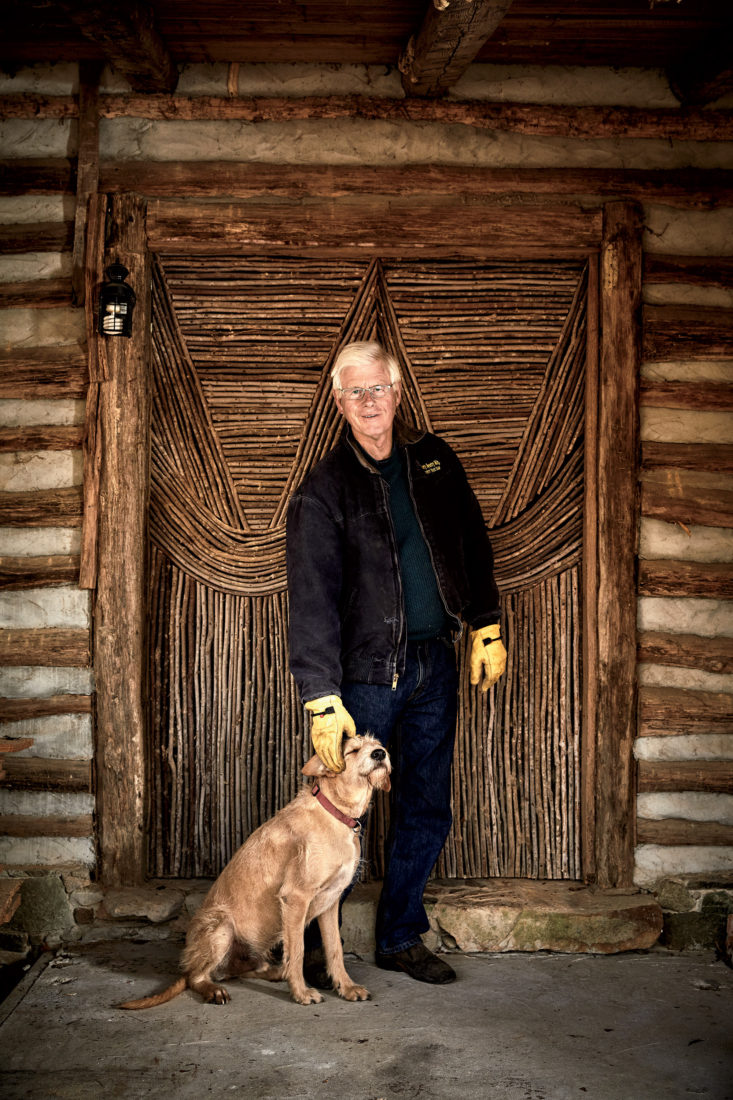

The Stickman

Wild, whimsical, wooden—from his artwork to his home, North Carolina sculptor Patrick Dougherty’s fantastical creations bend the imagination

Photo: Brie Williams

His story, like all of our stories, begins at home.

Even more so, though, for him, because before Patrick Dougherty moved to the patch of land where his house is now there was nothing on it but trees and scrub and rocks. He built a one-room cabin first—this was in 1975—and that’s what he lived in with his then wife, Patty, and their two children, the running water coming from a pump outside. You had to stand under a hose to bathe; the outhouse was just a few yards away. Patty worked as a nurse, and Pat stayed home with the children, and slowly, thoughtfully, meticulously, he created a world where there wasn’t one before, building another room onto the cabin, then a shed on the other side of a make-do drive, clearing more ground and using the trees and rocks he found to make the rest of it, with the help of friends from time to time. More than forty years later, paying a visit here feels like slipping through a tear in the fabric of reality; you’re in another realm situated right next to your own but incalculably distant from it. Almost every bit of the structures has been made by hand from the surrounding land, even the fences, not fashioned from traditional slats but branches, bark-free, golden. You’ve read fairy tales this home could be at home in. Crafted with a sneaky simplicity, the design is self-sustaining in both senses of that phrase. “I’m very lucky,” Dougherty says, “to live in my aesthetic.”

Photo: Brie Williams

A storage shed Patrick Dougherty built using materials he found on his property.

That aesthetic is made of wood, by hand, magical and at the same time very, very real. It’s like his work. Dougherty is a sculptor who shows us our dreams, and they are made out of sticks.

They’re not made of sticks, though, his sculptures. Not really. But that’s how people think of them, and it’s even what people call him, his unofficial nickname whether he wants it or not: the Stickman. His work is actually made of saplings, the smaller trees and shoots growing, or trying to grow, stunted, beneath a larger canopy of hardwoods and pine, or by a river, in a field, wherever he can find them. Dougherty has a wizard’s knowledge of bendability; he can’t use sticks because sticks are too brittle to bend, and when you see his sculptures, you understand why he needs them to: His work undulates. Straight lines are few and far between.

What do these sculptures look like? Like nothing else in the world. If you’ve seen one you know it, you haven’t forgotten it, and you won’t. They’re big, many of them very big, almost all of them big enough to stroll around inside. Some cling to pylons or walls, or roll across the tops of trees; others emerge from a lake, seeming to balance on the surface of it without making a single ripple. They pour through open windows and over balconies, or rise like a dirt devil from a leafy quad. His sculptures do impossible things. They could be homes for giants or trolls, the first shelters built by prehistoric men, Gaudí-esque mazes, giant vines, remnants of alien visitations, windblown towers, jokes. They are fun, joyous, friendly, inviting, and public, very public: art conceived by one, built by many, shared by all.

Photo: Charles Crie

Branching Out

Dougherty’s Sortie de Cave (2008), in Chateaubourg, France.

Since the early 1980s, Dougherty has created more than 275 of these sculptures, winning numerous awards, including the National Endowment for the Arts fellowship. You can find them everywhere from an arboretum near Chicago to a castle in France, a winery in California to a lake in Scotland, and in or around museums across the globe. Not a one of them is exactly like another. He designs each as a response to the site where it will spend its lifetime, which is brief, though every work has the same buoyant spirit and charm. The materials are gathered locally, harvested so that the roots can regrow: sweet gum and maple down South, alder and willow in Colorado, elm in Kansas, cherry in Massachusetts, eucalyptus in Hawaii, assembled to the coordinates of Dougherty’s design by the artist and the many volunteers who come out to help him—these are not objects that one man can put together. From their inception, even before their inception, they’re products of the hard work and imagination of many people. Not art by committee, though: It’s art by cooperation. When Dougherty started out, the style was called Arte Povera, as well as land art, site specific, and environmental. Now some in the art world refer to it by another name: farm to table.

Whatever worn-out clichés you might use to pigeonhole artists—their sometimes airy, occasionally volcanic natures, their petulant genius—do not apply to Dougherty. He comes across as a stand-up guy, the type who believes there are no strangers, just friends he hasn’t met yet. It sounds like an odd thing to mention, but he’s bigger than he looks. He’s about six feet three inches tall, and solid, strong, with a head full of thickish white hair brushed to one side boyishly, you might say—or might not say, depending on how comfortable you are calling a seventy-one-year-old man boyish. He looks a little bit like Ed Begley, Jr., and is genuine, down-to-earth, forthcoming; he speaks in paragraphs, without jargon, is very smart but isn’t interested in making sure you know just how smart he is. A North Carolina boy, and it shows. That’s Pat Dougherty.

He lives near Chapel Hill off one of those two-lane roads that don’t seem to go anywhere in particular unless you live in Chapel Hill and know that it’s the perfect shortcut from Highway 54 into Hillsborough. There are ten buildings of some sort on his twelve acres: the house he and his wife, Linda, live in, a house for the chickens, an old outhouse, two woodsheds, a garden shed, another small shed behind the house for “stuff,” a toolshed, and two workshops, one for Dougherty and the other for his son Sam, who is twenty-two and already a master potter. Bamboo marks the edge of a winding trail; stone walls appear to rise naturally out of the forest floor, walls the way they used to make stone walls, with one carefully chosen stone at a time. To me, a man who avoids hammers and nails as if they were snakes, the structures are clearly the work of a seasoned carpenter. But they’re not: Dougherty started out a suburban kid; his father, a doctor, didn’t own a single tool. The house he lives in is the first house he ever built. He had never done anything like that before. Never stacked a stone, hewed a log, made an outhouse (abandoned for years now with the advent of plumbing, but still standing). He learned on the job. Anyone, he insists, could do it. “What you do wrong eventually turns out to be quaint,” he says, smiling. “You can call it personality.”

Photo: Brie Williams

The screen porch.

The lives of artists become mythic over time—not to the artists, but to us, who admire them—and every myth gets its creation story. We want to know when it all began. We want to see that moment the straight and narrow twisted, when the new and unique trajectory imposed upon the old conventional one. Sometimes that moment is hard to find, and sometimes it needs to be completely made up, but not in Dougherty’s case. With him, there’s a day you can point to and say, Here. Right here. If this day had never happened, neither would the rest.

The day he found a fallen tree.

Until that day, his biography reads like a preface to another man’s life. Dougherty was born in Oklahoma in 1945 and raised in North Carolina, graduating from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. During the Vietnam War, he worked at a military hospital in Germany, returned, and then received an M.A. in hospital and health administration from the University of Iowa. He became an administrator at a hospital in South Carolina, married his first wife, Patty, and in 1975 moved back near Chapel Hill, where he was in common parlance a househusband and home builder. But he had G.I. Bill benefits in his pocket and, when the kids were older, decided to use them: He went to art school. He knew he wanted to be an artist—he wanted to make things. At the time, he just wasn’t sure what.

Photo: Brie Williams

Work gloves hung in the artist’s studio.

His first assignment was vague, with almost infinite parameters: Construct something out of wood. Anything. Maybe a little box or a birdhouse. He and his best friend, Scott Bertram—who has remained his best friend for more than thirty years—came upon a red maple, uprooted in a field, lying on its side. Here is where the force of Dougherty’s character was exposed and reckoned with, and where the future, unknown and unseen, presented itself to him. They put the tree on top of the car, crushing part of the roof, and took it to school, where Dougherty stripped it and oiled it. And voilà: big, wooden, original, dangerous. This is the direction he was headed in, that thing he was meant to make. He came to it as a naïf, the same way we come to his work now.

So that’s the story, the myth, most of it not made up at all.

In 1982, his very first work was included in the North Carolina Biennial Artists’ Exhibition, and since then, over the course of the last three decades and the creation of all those sculptures, Dougherty has honed his process. No matter where he is, no matter the scope of his design, the scaffolding of his ideas is the same. He does a site visit months before he’s scheduled to be there, and lets the setting speak to him. “It all happens in the subconscious,” he says. For such a practical man, he uses that word a lot. The design and building decisions he makes, the ones that determine exactly where a sculpture goes, how it’s going to look, how long it’s going to take stage by stage, and how hard it’s going to be to make—all that happens at the same time. “The subconscious is where everything ends up going, whether you know it or not.”

Photo: Brie Williams

Images of previous commissions.

Every sculpture takes three weeks to make. Not on average, or in general, but exactly. Three weeks from the gathering of the wood—a tractor-trailer load, five or six tons—to the gathering of volunteers, and then to the slow and steady accretion, layering, the height and width and depth of his vision, branch by branch, sapling by supple sapling. Very much unlike the way most art is made—where the artist is holed up, alone, in an office or studio—his work is done in public; it’s a performance piece. Passersby stop and watch; cars slow down, drivers stare. “It’s bottom up,” he says. The only part of the process done in solitude is the outline of the design itself, and in many cases that’s drawn on the boarding pass for the flight there, or the back of an envelope, hotel stationery. “I lay out a general plan,” Dougherty says, “and take advantage of the imminent moment—the moment a viewer sees it, the feeling they’ll have. I set parameters and then narrow them, and work toward how a piece should feel.”

And it is work, hard work. Eight hours a day in whatever the weather throws at them: rain, snow, blistering heat; constant collaboration with volunteers and the institutions that hired him, even with the curious public, who stop every few minutes to ask him the same question: What are you doing? “Someone is calling the police on the first day and inviting me to dinner on the last,” he says. This is one reason Dougherty has no imitators: It’s just too arduous to do what he does. It’s easier to take advantage of rooms with roofs and walls and air-conditioning and a couch for that no doubt well-deserved, creative nap.

Dougherty doesn’t nap.

How many artists set out to make something that by its very nature is ephemeral? How many want to? “I tell the people who hire me they’ll get about three years out of it: one great year, one pretty good year, and one…” He shrugs, shakes his head, and doesn’t say it but it’s a fact: The third year is when an untended sculpture will really start to fall apart. After which, whoever commissioned the work might chip it, burn it, or dump it into a lake for the fish.

Sounds brutal. But this is okay with Dougherty. His goal has never been to make things that last “forever,” however long forever turns out to be.

2002

Call of the Wild, at the Museum of Glass in Tacoma, Washington.

1 of 4

Photo: Paul Kodama

2003

Na Hale ‘Eo Waiawi, at the former Contemporary Art Museum in Honolulu, Hawaii.

2 of 4

Photo: Rob Cardillo

2009

Summer Palace, at the Morris Arboretum in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

3 of 4

Photo: Fausto Braganti

2015

What the Birds Know, at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts.

4 of 4

“I think art is about what happens the moment you encounter it,” he says. “It’s about the intensity of the experience. I think that’s why people enjoy my sculptures. Everyone can find an association with it. Maybe they walked in the woods as a child, and my work reminds them of that. Or they have a love of the natural world. Maybe they’re concerned about climate change, or the disappearance of farms. So many things. The work is accessible, inviting, and you don’t have to go to a museum to see it.”

I tell him that a friend of his called him “frugal,” and he laughs. “I guess so,” he says. “The other way to look at it is that I appreciate reclaimed material, recycling, usability.” Life in things that don’t appear to have any, this is what Dougherty discovers, and he finds it all over the world.

Dougherty sees the transience of his art no differently than he sees the brevity of life itself. He’s past seventy now, and doing what he does isn’t easy; it’s demanding and very physical, and he’s working ten months out of the year. At one commission a month, that’s ten sculptures. This means digging a lot of postholes, climbing scaffolding stories high, tromping through dark forests, enduring long, grueling days. How much longer can he keep this up?

He shrugs, almost as though he hasn’t thought much about it.

“I might cut back to five a year,” he says. “I don’t know. Then I could make some smaller things here at home. Not sure.”

He just finished a job at the Bay Area Discovery Museum in Sausalito, California, and next up is a commission in February close to home at Durham’s Sarah P. Duke Gardens, and then it’s on to the Gibbes Museum of Art in Charleston, South Carolina, in March. He’s not slowing down at all. His son Sam has signed on to be his assistant for the next couple of years. “He’s my bridge,” Dougherty says, “to whatever comes next.”

But his work has never been anything he has done alone. This is the difference between him and every other artist I know: He depends on the rest of us to create his singular visions. That may actually be the most important part of it to him—the rest of us helping. He builds these grand sculptures made of saplings, one after the other, and he never thinks of them again. But here’s what he does think about: his gloves. For every installation he uses a new pair of gloves, and when he’s done he has everyone who helped him sign the gloves, left hand and right. He has hundreds of them now. A pair of gloves is the only thing he keeps, the only evidence that his work, so much of it gone already, happened at all, while we get to walk through the forests of his dreams.