One of the best classes I attended at Auburn University in the 1990s wasn’t taught by a professor. It was taught by one of the janitors at Sewell Hall, the athletic dorm at the edge of campus.

You need to go back to the time and imagine the music emanating from the doors of the three-story brick structure. Depending on the athlete, you might hear some Tupac, Tag Team, or Garth Brooks and Alan Jackson. Toss in some Metallica and Vanilla Ice and you get the idea.

But if you ventured to the edge of the third story, overlooking the parking lot and baseball field, you might have heard a different sound coming from room 308. A white boy born and raised in Alabama in the eighties was playing Otis Redding, Johnnie Taylor, Carla Thomas, Wilson Pickett, and Aretha. You know the music. Tunes you’d find on every ’60s soul compilation CD: “Dock of the Bay,” “Who’s Makin’ Love,” and, of course, “Mustang Sally.”

My out of step, out of place playlist wasn’t missed by our dorm’s janitor, Willie.

“How do you know about this old stuff?” he asked. “This is my music, man.”

I showed him the CDs I’d collected since high school, and he took a lot of interest in my Wilson Pickett and Johnnie Taylor, mostly recent reissues from Stax Records, the legendary house of soul in Memphis. Then Willie started asking me about other soul singers. “Do you know…Maceo Parker? O.V. Wright? Ann Peebles? Syl Johnson?”

I shook my head. A lot of these artists weren’t easily found at my Record Bar bin at the mall. A few days later, Willie knocked on my door with some tapes. He’d recorded Wright’s seminal “Blind, Cripple, and Crazy,” “A Nickel and a Nail,” and “He’s My Son (Just the Same).” He’d also added some “I Can’t Stand the Rain.” The original by Ann Peebles, not the Tina Turner version I knew.

The man was giving me an education on deeper soul. Music that had meant a great deal in the Black community but had never really crossed over to white audiences. At the time, I thought I knew everything there was about soul music of the sixties. But admittedly, I didn’t know anything about the deep, cool soul of the 1970s, beyond some Al Green hits.

In the years that followed, those tapes turned to shit. I had graduated and ended up in Tampa working as a newspaper reporter. I became a frequent guest of Vinyl Fever, a terrific record shop in town. And from there, I was able to piece together a new collection of that deeper soul, one that included a hell of a lot of music from Hi Records out of Memphis.

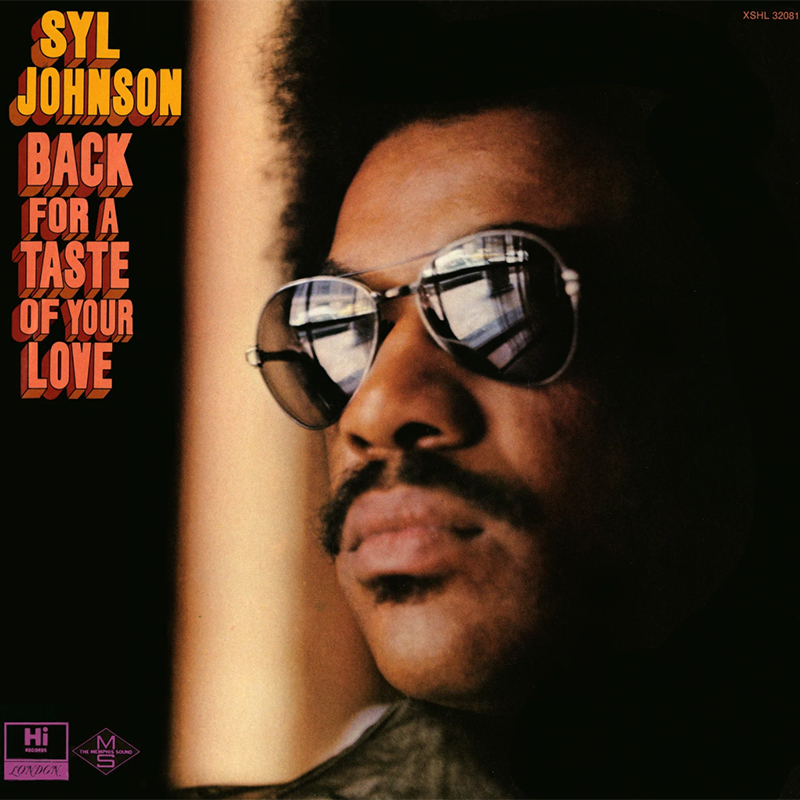

I think it was then that I really came under the spell of Syl Johnson, a Mississippi native who died this past weekend at the age of 85. Only then was I able to listen to his entire albums, not just select cuts. And damn. How did the entire world not know about Johnson? Over the years, his music has provided comfort, pure pleasure, and inspiration. Just last fall, I started outlining a new novel while listening to his debut album for Hi, Back for a Taste of Your Love.

Grittier, edgier, and more blues-inspired than Al Green, Johnson’s music had a transcendent quality that I couldn’t get enough of. Sadly, unlike a lot of those other soul heroes, I never got to hear the man perform.

But what a life. What a legacy.

About as close as I ever got to Syl Johnson was spending a memorable day at Royal Studios in Memphis, where he recorded most of his great hits. My friend, the music writer/historian Andria Lisle, had brought me to Royal to meet Willie Mitchell, the legendary producer and owner of Hi Records.

Al Green was supposed to be in that day to lay down some songs. He never showed. His famous white Bentley had broken down. But back in the day, Al Green had gotten to Royal first. To hear the Mitchell family tell it, Syl Johnson was almost Hi’s main player. If he’d just come down to Memphis earlier, Mitchell was ready to make him a star. But this was 1968, a bitter and complicated time for the city and for many artists trying to make sense of what to do after Martin Luther King Jr.’s death. Still, he went on to make four brilliant albums for Hi.

I recommend them all. As well as the box set Complete Mythology, which covers his time before connecting with Willie Mitchell.

Back then and still today, Royal Studios is a time capsule to a magic era of soul. I walked the threadbare red carpet and old faux paneled wood walls where Johnson recorded some of my favorite songs.

I was drawn to a sagging shelf where I saw master tapes, boxed and marked with recording dates. I was shocked they were just there, out in the open, and not in a safety deposit box somewhere. After all, Johnson’s music was magic. Blues, soul, heartbreak, love, and loss. Regret. Racism. His songs filled with hope and anger. But always there was that cool, unnerved voice, hanging toward the back beat. Any way the wind blows; it’s cool with me, as he sings in his signature hit.

I was saddened to hear Johnson spent many of his later years bitter about never reaching a higher level of fame. He even quit music in the eighties to start a fish and chips franchise in Chicago. But he did at least get some much-deserved recognition in the last ten years of his life. He became the subject of a terrific documentary by Rob Hatch-Miller called Any Way the Wind Blows. The film explores his early years in Holly Springs, Mississippi, just up the road from my home in Oxford, and his move up to Chicago, where he came in contact with Muddy and Wolf and even played with Junior Wells and Jimmy Reed. All those blues influences coming through in his later recordings.

I watched the film again on Sunday after I found out he’d died.

One of the things I learned is that back in my college days, Syl Johnson had always been there. Maybe not in his hits like “Stuck in Chicago,” “Wind, Blow Her Back My Way,” or his version of “Take Me to the River,” but in samples from hip hop music that had been playing all around me at the football dorm. Johnson’s hit “Different Strokes” has been sampled countless times, providing funky and gritty tracks for Wu Tang Clan, the Beastie Boys, and Public Enemy.

Syl Johnson was always in our periphery. But sometimes it takes a good teacher to point you in the direction of the classics. And a deeper soul. For that, I will always be grateful.